‘The line between performing and writing is a little fuzzier than I think we often think of it as.’ Those are John Darnielle’s words, in an onstage discussion about the possibility of authenticity in a cover performance. It’s not a claim I’d care to run past an intellectual property lawyer, but the Mountain Goats project has always involved inhabiting stories, often more invented than personal. This mobility of perspective feels of a piece with John’s comments which I discussed last time about his connection to a bardic, storytelling tradition. I can see how, together, they might lead to an understanding of composition and performance alike as different routes – or twisting alleyways – towards this kind of immersion in experience.

Mountain Goats live performances have certainly always felt immersive, not least because of the full-bodied commitment of Darnielle’s (often shoeless) delivery. They have also circulated for a long time in online bootlegging communities – partly because, as an active poster on music forums, the artist himself was relaxed about their distribution, and partly because of the common fan desire to hear the songs differently. The feeling behind this impulse is one John recognises: ‘I was always most thrilled when the live version was significantly different from the recorded version. To me, that said that the performer was still engaging with the material, and still involved in the blood and guts of the song.’

The absence of the boombox frame is also surely part of this: songs we’re familiar with in confined spaces can show their ability to breathe, stretch, and occasionally roar like their singer is being flayed alive. Shows, especially solo, tend to figure a certain responsiveness to audience requests across the breadth of the catalogue. For the keen-eared, there are off-mic adlibs and on-mic lyric changes. ‘This Year,’ a song you might have listened to a thousand times, hits a little differently when the singer says he feels ‘the heroin inside of me hum’; ‘Palmcorder Yajna’ sounds more desperate than ever when the narrator looks at the room of tweakers around him and hopes for an opportunistic arsonist to ‘incinerate all these fuckers in it.’

These are both, of course, songs rooted deeply in personal experience, and so there’s a part of me that feels intensely grubby for finding their most extreme versions the most exhilarating. I take some comfort in Darnielle’s acknowledgement that fans have ‘made it plain that they’re happiest when a performer sweats… if people come out to see you play, you oughta be willing to bleed a little.’ That said, he’s made it clear enough over the years that while audiences like to see him stomp and howl, it’s no longer the aspect of his art that interests him most in the recording studio – that quieter moments like ‘Pale Green Things’ and ‘Hair Match’ dig deeper, ask for more from their author, than the songs with most of the screaming in them. Even in this period, Darnielle takes as a sign that he’s gotten ‘pretty into the story’ of ‘Waving At You’

the way I get real quiet during the end of the vocal. To me, that’s the signal that I’m getting so involved with the plotline that I can’t really tell the difference between myself and the narrator any more. That is really the point at which I feel like I’ve succeeded in getting somewhere. Everybody else assumes the louder I sing, the more deeply I’m feeling the emotions, and I do try to oblige, but it’s the quiet moments where the shadows sort of start to flesh themselves out.

Perhaps it’s indicative of something in me – in many of us – that my first instinct is to take outward expulsion rather than inward reflection as the ultimate expression of authenticity. Some of this is doubtless a kind of lazy rockism: a musical worldview Kelefa Sanneh defined in the New York Times as ‘idolizing the authentic old legend (or underground hero) while mocking the latest pop star; lionizing punk while barely tolerating disco.’ Comments on that genre by ‘a second-rate English songwriter from the 1980s named Morrissey’ make clear the racial investments of such a position – and as Sanneh asked in 2004, ‘when did we all agree that Nirvana’s neo-punk was more respectable than [Mariah] Carey’s neo-disco?’1

A rockist, for Sanneh, is not just someone ‘who champions ragged-voiced singer-songwriters no one has ever heard of,’ but it would still be laughably easy, in a newsletter about the Mountain Goats, to make a habit of ‘extolling the growling performer while hating the lip-syncher.’ To do so, however, would be to read the songs against their author. In 2010, a fan started a waggish single-issue webpage called ‘The Mountain Goats Will Cure Your Bieber Fever’; three years later, John wrote and recorded a ‘Short Song for Justin Bieber and his Paparazzi’ with the central message, ‘you don’t have to leave Justin alone, but don’t be an asshole.’ The website is no longer online, Darnielle’s empathetic song having outlasted the fan’s light culture war manoeuvring.

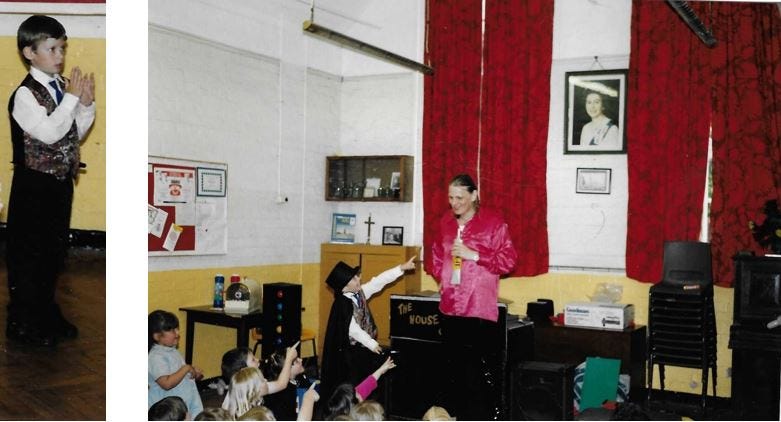

In the photo on the left above, taken at my sixth birthday party, I look like a figure praying for a benefactor’s soul on the wing of a medieval triptych, but I think I’m actually in the middle of a series of dance movements. I’m concentrating intently; I look almost worried. With a formalist’s, and/or a Catholic’s, chagrin at breaking the rules, I’m including a second picture from 1996 to give you some context. The laminated posters pinned to red felt, the stacked brown plastic chairs, and the decor – a free-standing crucifix and a framed photograph of the young Queen Elizabeth II – all signify ‘English village hall in the mid-90s.’ Meanwhile, the tower of coloured lights and the man in a pink shirt, with slicked-back hair, standing in front of a PA unit labelled ‘THE HOUSE OF MAGIC’ scream ‘baby’s first disco.’ The DJ is also a magician, and I’m still the only person in the room wearing a patterned waistcoat.

I don’t know what I’m dancing to – having checked the dates, I’m surprised to realise that in June we’re a few months too early for the Spice Girls’ ‘Wannabe,’ before which I hadn’t even realised I knew something called ‘pop music’ existed. But this must, in any case, be around the time I started to become aware of something you could call culture beyond me, my family, my friends, the animals and vehicles in my immediate area. Part of me would like for the song that first truly lit up some essential synapses in my brain to be Pulp’s ‘Common People,’ which came out in May 1995 and which I do remember at some point hearing in the car with my mother.2 Whenever that was, the experience was one which I didn’t have equivalent words for until I read Springsteen’s comments on the first time he heard Bob Dylan: it ‘sounded like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind.’ But I think this was later – looking at the list of the year’s charting singles in the UK, my pop initiation seems most likely to have been the year’s British Eurovision entry, ‘Ooh Aah… Just A Little Bit,’ by Gina G.

The House of Magic could feasibly have been spinning ‘Wonderwall,’ ‘Gangsta’s Paraside,’ ‘Three Lions (Football’s Coming Home)’3 or ‘Mysterious Girl.’ It could even have been a boyband cover of a singer-songwriter: the 1995 Christmas number one had been Boyzone’s take on ‘Father and Son,’ a song I love but, mercifully, don’t recall having actually heard before the age of 30. Given the penchant of children’s party DJs to prioritise guaranteed bangers which lend themselves to choreographed dance routines, it’s not implausible that I’m listening to ‘The Sign.’ As John reminded a 1996 London audience, the hit song by Swedish four-piece Ace of Base ‘transcends national boundaries. It was number 1 in 27 countries,’ though it actually only reached number 2 in Britain in 1994, kept from the top spot first by Mariah Carey’s ‘Without You’ and then by ‘Doop,’ by the Dutch Eurodance group Doop.

I’m pretty sure I’m not dancing to ‘The Sign’ – there’s no way I’d have known the movements John came up with, driving through the south side of Chicago two years previously on his and Rachel Ware’s first East Coast tour:

On the way from Columbus into Chicago, when we heard ‘The Sign’ on the radio, somebody got ready to turn the station and I said, ‘What is wrong with you? Does God hate you or something? Has he not taught you how to love? Is that what’s wrong with you, is that why you changed the station just now Liz?’ … So then we pulled off in Gary, Indiana and bought the whole album on cassette, put it into the tape deck, and just kept rewinding… Listened to it once, twice, three times … eight, nine, ten… by the time we got into Chicago, we had choreographed a dance.

But whether or not he performed these hand signals at the time, it’s fun to think that a few months earlier and a couple of hours away from the south side of Lincolnshire, the artist who would become my favourite singer was yelling his head off at an unplugged record store show in Covent Garden, haranguing my countrymen to join him on the chorus of his ‘favourite song’: ‘once, when people wouldn’t sing my song with me, I made them bring the house lights up… I went chasing after the British, in the Rough Trade shop – they don’t like it when you come at ‘em and tell them to sing along with you, it makes them very nervous.’

Why is John Darnielle so keen for his audiences to sing ‘The Sign’? Not out of ironic appreciation, a concept he refused to recognise in an interview with Daniel Handler for The Believer:

At some point you might have told yourself and others that you listened to the Backstreet Boys because it was funny. But in fact, you were enjoying it; it’s just a different kind of enjoyment for you … I think most of that irony is an attempt to say, “These aren’t exactly my kind of people, and I don’t picture myself sounding like that, but I still like it.” I don’t believe in ironic appreciation. I think if you like something, the core of it is you like it.

One thing the singer might have liked about ‘The Sign,’ enough to record a studio cover with Ware on bass for 1995’s Songs for Peter Hughes, could be its familiar preoccupation with cryptic symbols, like the unbreakable code ‘written in tall clear letters on your face’ in ‘The Recognition Scene’: ‘the things that you hallucinate, if they are true for you, are as true as anything in the world, and you are entitled to them, and when people say that you’re not, you don’t have to listen to them.’ Darnielle’s minor modification to the chorus lyric, changing one key word from ‘life’ to ‘love,’ also brings out a deeper resemblance to his narratives of doomed couples who don’t seem to know how to talk to each other: ‘For so many years I’ve wondered you who are / How could a person like you bring me joy? … Love is demanding without understanding.’

But from his comments to Handler, it seems simpler than this: ‘I love Ace of Base. That’s part of why I used to do that song. I thought it was a great fucking song. I suspected everybody else also thought so, but that everybody would want to say, “I like that song, but it’s really stupid.”’ Perhaps there’s something inherently comic about the vagueness of ‘The Sign’’s evocations of the epic, but Darnielle himself knows the attraction of what Keats called ‘Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance.’ Looking up at the pale moon and seeing merely ‘a lot of stars,’ as opposed to a ‘sky gone crazy with stars,’ is partly a matter of judgement, but also one of genre. ‘I like a lot of singer-songwriters, but at the same time when I listen to them, it sounds like watching my peers work in the workplace,’ as John told Handler: ‘I’d be more interested in going to a factory and seeing people work there because I don’t do that kind of work.’

This ought to serve as a reminder that pinning down where the Mountain Goats are coming from musically is more difficult than one might think. Dylan comparisons are immediately stymied by John’s conscious attempt to avoid listening to Dylan for as long as possible, precisely out of a desire not to fall under such an obvious influence. It’s easier to map his love for Joni Mitchell – ‘Blue is the greatest singer-songwriter album of all time imo’ – Randy Newman – ‘there’s not another songwriter working who doesn’t stand in awe of you’ – and Leonard Cohen, who he saw in concert on the 1988 I’m Your Man tour and to whom his brief elegy evokes the same emotion:

Responding to a fan on Twitter, he lists the following artists along with Joni as his main listening fodder when the project started: ‘Steely Dan, W.A.S.P., the first Ice Cube full-length, and the Gun Club.’ To these we might add, from frequent mentions elsewhere, Jackson Browne, the Cocteau Twins’s Victorialand, and Lou Reed, whose album Transformer broke the teenage John out of a very different musical phase: ‘my prog friends … [would] always argue that the only way you could like Lou Reed is if you were in some way laughing at the fact that he couldn’t sing or that the songs were so simple. By the end of that year, I decided that Genesis and all that prog stuff had to be destroyed because it was so much more pleasant to listen to this stuff that wasn’t trying so hard to be impressive musically.’ And then, of course, there’s Alma Mater by the Stockholm Monsters – a Peter Hook-produced post-punk record by a band from Manchester which John once called ‘incontestably the greatest album of all time, bar none, all records coming in its wake being weak pretenders to an unassailable throne’ – and Nick Cave, at whose 1984 Pasadena set a 16-year-old Darnielle experienced ‘total catharsis,’ an encounter for which there is, incredibly, some visual evidence:

If the Mountain Goats don’t sound that much like any of these guys – though Cave’s apocalyptic strain certainly offers some lyrical parallels – the reasons are likely somewhere between technique and transmutation. We should also keep in mind the apparently fertile and self-sufficient indie-rock scene in the Inland Empire from which the band emerged, clustered around artists like Wckr Spgt, Refrigerator, Franklin Bruno and Peter Hughes’s DiscothiQ. In a wider context, John has referenced the likes of Smog/Bill Callahan and Neutral Milk Hotel’s Jeff Mangum as fellow travellers, along with David Berman – a songwriter to whom John paid tribute as ‘the best of’ his generation after his untimely death.

By 1996, the Mountain Goats had established an audience, and had also been lightly chastised by two record labels for releasing Nine Black Poppies and Sweden on the same day. I see this time as in some ways a period of consolidation. More confident takes on early compositions like ‘Alpha Double Negative: Going to Catalina’ and ‘Going to Kansas’ sit alongside experiments – notably on ‘Going to Utrecht,’ ‘Full Flower,’ and perhaps most successfully, ‘Prana Ferox’ – with the kind of fizzing, scribbling electric guitar I associate with post-grunge American college-rock, the closest the Goats ever came to the sound of scene stalwarts like Sebadoh, who John called it ‘the biggest deal’ to support in 1994.

This was, of course, also the year when ‘young Kurt Cobain / Snuck out to a greenhouse, put a bullet in his brain.’ Darnielle doesn’t seem to have been a Nirvana superfan: at the height of their fame, he was ‘listening mainly to Slayer,’ and in 2001 he called Nevermind ‘more pet rock than punk.’ But the death of Elliott Smith, not long after these comments, may have set some wheels of recognition turning: ‘even through his ascendance from underground wonderkid to Semi-Public Figure of Renown, [Smith] felt like somebody we know. When I saw him on the Academy Awards a few years ago, he looked so much like One Of Us after having stepped through the wrong door that the whole thing filled me with the sort of exuberance usually reserved for when one’s home team has won the Stanley Cup.’ I can’t say if Cobain ever felt like somebody Darnielle knew, but I do know he was born in 1967, took a lot of drugs in the Pacific North-West, and didn’t make it out alive. Kurt was young to the 37-year-old tracking ‘Love Love Love’ in Prairie Sun Recording Studios, a decade later – when he died, the two singers would have been the same age.

From Ace of Base to Slayer, Ice Cube to Nirvana, I’m mostly struck here by the breadth of Darnielle’s listening in what must have been a more polarised music culture than the one we’re now used. I’m old enough to remember when buying a CD you didn’t like at first meant you were stuck with an investment you might as well put some time into, but I can’t imagine following the philosophy Darnielle sketched out around this time, that ‘if you have a really strong reaction against something, you should buy the record, right? And find out why.’ This is a belief that led the singer both to another of his favourite albums, Mercyful Fate’s Don’t Break The Oath– after initially noting simply that King Diamond’s voice ‘asks a lot of you’ – and to the complete singles collection by a band he had ‘always hated’: Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons. With time and money on his hands in his Norwalk employee housing apartment, Darnielle told an interviewer that he ended up buying a guitar and a tape-deck to cut his own covers of them. No ‘Can’t Take My Eyes Off You,’ no ‘Going to Alaska.’ Tilt your head one way: ‘The sight of you leaves me weak / There are no words left to speak.’ Tilt it another: ‘I am losing control of the language again.’

*

This week, unusually, there’s also a B-side to the episode. It’s also about covers, and my experiments with recreating the early 90s Shrimper sound, on the same model of Panasonic boombox, in my office in Newcastle. I’ll be talking about room sound, angry mastering engineers, and the challenges of working with live animals onstage. If that sounds like something you’d enjoy hearing, subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, and keep an eye on the feed.

This week, Richard is getting into Tim Robinson and 80s horror movies.

I wrote much of this post in two coffee shops, the first of them playing ‘Random Rules’ by the Silver Jews; the second, ‘We Don’t Play Guitars’ by Chicks on Speed, who I once saw in a curious mixed bill, along with James Brown, supporting the Red Hot Chili Peppers.)

John Darnielle described its parent album, Different Album, as a ‘for-the-ages masterpiece,’ but it still would have been an unusual choice for a children’s party.

Be grateful I didn’t call this series ‘Thirty Years of Hurt.’

1996: 'The Sign (Live)'