‘My inner 12-year-old is, like, so fucking stoked that I name an album that we made and people just go “Yeah, I would like to tell you that I like that album!”’ That’s John Darnielle onstage at the Bottletree Café in Birmingham, AL on 22nd June 2013, addressing an audience which has just audibly whooped at his mention of Tallahassee – the studio album which, a decade or so earlier, had effectively launched the Mountain Goats as a full-time, professional recording outfit. Whether the Heart-loving pre-teen whose spirit John is invoking here could have anticipated that album sounding anything like Tallahassee is, perhaps, beside the point – though the record, by design, doesn’t closely echo much else being released on indie labels in 2002, it doesn’t sound a whole lot like ‘Barracuda’ either.

I didn’t hear the Mountain Goats’ first release on 4AD until three or four years later, but on the evidence of this photograph of myself at the time, I’m not sure I would have been ready to get all that much out of it. The Offspring hoodie comes from a stall in Peterborough market – you’d have found Nirvana, Linkin Park and Limp Bizkit hanging up beside it, and my nascent CD collection looking much the same.1 I remember distinctly knowing every word to the California skate-punks’ – Garden Grove, no less – 1997 opus Ixnay on the Hombre, though looking at the lyrics today rings so few bells that they might as well be a language I’ve forgotten how to read. I’m not twelve any more, so in a way they are:

I’m always feeling steered away

By someone trying to tell me

What to say and do

I don’t want it

I gotta go find my own way

I gotta go make my own mistakes

Sorry man for feeling

Feeling the way I do

Oh yeah, oh yeah

Open wide and they’ll shove in

Their meaning of life

Back then, though, it was cool to hate – teachers, school, and the people around me – and easy enough to do so with what another of my pop-punk faves referred to as ‘reckless abandon.’ The teachers, of course, were mostly perfectly helpful, though that didn’t stop us roasting them for making minor, old-person mistakes like asking ‘When’s Green Day?’ when they saw the band logo on somebody’s pin badge. There were other, more productive ways of meeting us where we were: few interventions in my life have made more of an impact than the moment when I was taken aside after an English lesson in which I’d made a snidely homophobic joke, and told by the teacher that she knew a boy my age who was gay and happy with who he was. The school itself was a state-funded selective institution, which gave me good educational prospects – demonstrably, I’ve since learned, at the expense of others. Bourne Grammar wasn’t without its problems – the lingering banks of demountable classrooms, the new headteacher fresh from the private sector and determined to emulate it as sycophantically as possible – but its academic focus set me firmly on the path towards the kind of life I’ve ended up living.

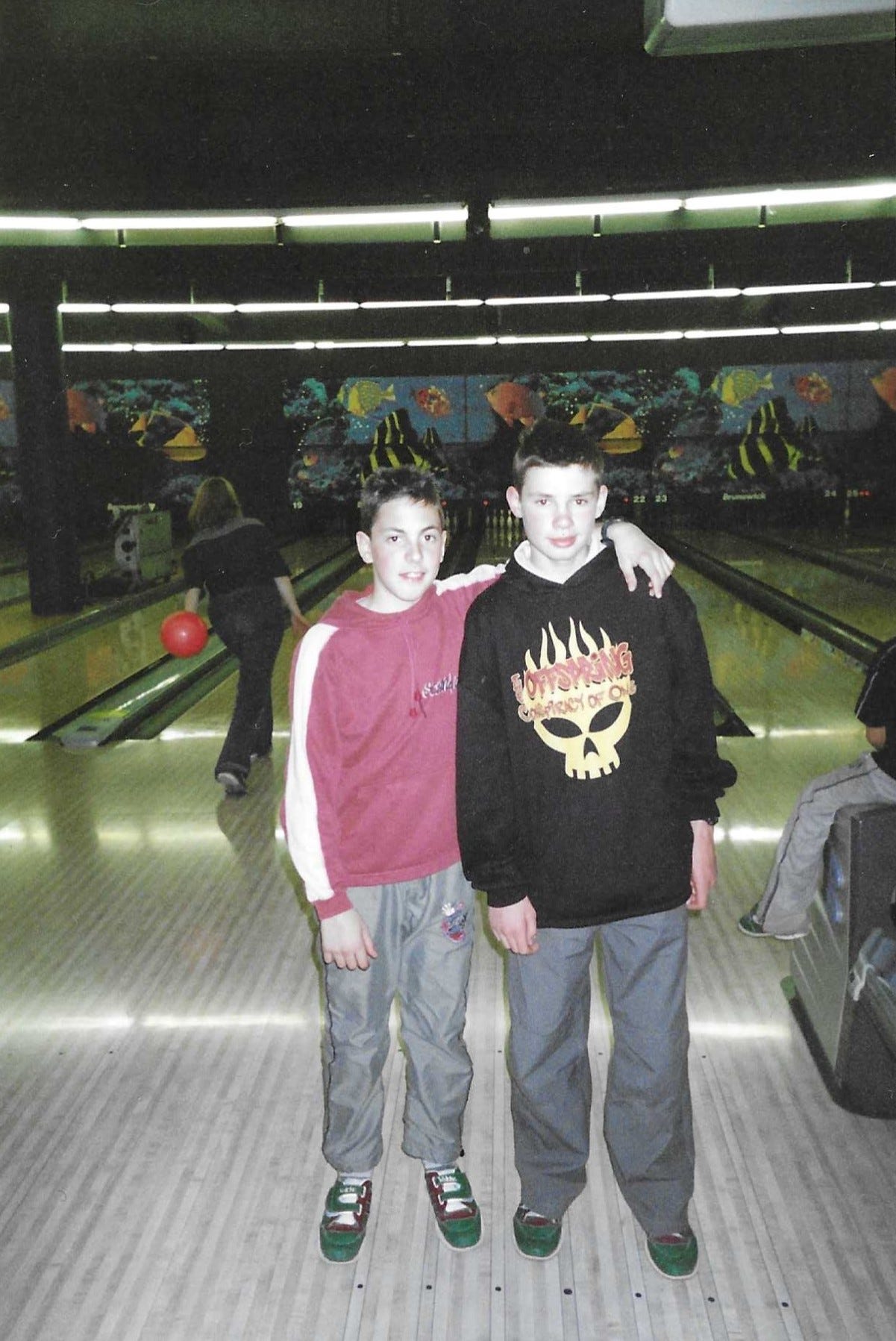

One of the many opportunities it afforded was a French exchange trip, and the above image of me and my opposite number Hugo, both gangly and shapeless in a bowling alley in Normandy, must be one of the first taken on a camera that I owned myself. This new development, barely meriting a remark at the time, nonetheless brought with it the very adult possibility of control over the images that were taken of me – and, of course, those I took of others. On the same trip, I shot a couple of a classmate, her flyaway hair straggling against the wind near the cathedral in Rouen, and on returning, emailed them around my Year 8 peer-group with the caption ‘Embarrassing Pictures of Anna Parker.’2 Not only did we have classes together all week, we were also in the same drama group on Saturdays, which adds an extra layer of stupidity to the act’s inherent cruelty: I was going to have to see her, a lot, so either I hadn’t thought about that or I just didn’t care. It’s hard now to imagine a more embarrassing picture from this visit than the one I’ve included here, unless you count the ones where I’m wearing WWE-branded pyjamas.

In mapping out the difference – in some ways small, in others enormous – between myself at twelve and myself at fifteen, I suppose I’m also wondering how I would have felt if I’d come across the Mountain Goats in this context. I’ve quoted before from Peter Coviello’s formulation that ‘loud, frantic, and concussive’ music can offer a space to explore ‘your furies … as something other than poisonous.’3 This works in part, I think, by giving that poison somewhere to be besides the body: by indulging in the fiction that all of that pain, hate, fear, shame, or whatever else you want to get rid of is over there, in its own little sealed capsule, on the other side of a door you can choose to walk through whenever you decide by pressing play, and close again when the song is over.

From Jackass to Will It Blend?, I recall the 2000s as a decade with a particular affinity for wanton destruction. I bought a skateboard I couldn’t use, and set my laser tag name as Black Mamba. But pubescent people tend to want to break stuff anyway: rules, narratives about themselves constructed by others, and in my case at least, a ceramic dragon my mum and I had painted together after bringing it back from a Camelot-themed holiday in Cornwall, letting it slip out of my fingers to the floor out of nothing more than a kind of spiteful curiosity. What a relief, then, to have the option of a space to vanish into where something (a voice, a guitar, a drumkit) is continually being bashed and battered and torn, without any of the mess – or the responsibility – landing at your own feet afterwards.

‘No Children’ was the first of John Darnielle’s songs I ever heard. As Daoud Tyler-Ameen noted for NPR, the track’s ‘severity’ might not ‘hit you right away’ on the first listen, not least because of the hummable swing of Franklin Bruno’s ‘barrelling, old-time saloon piano,’ but nonetheless it contains a good number of phrases which might fit Coviello’s bill. What twelve-year-old hasn’t thought I hope you die, or wanted to piss off the dumb few and never come back to this town again / In my life? Much as in ‘The Meaning of Life,’ the narrator – the husband in a doomed partnership known since the first of their recurring appearances in Darnielle’s work in the early 90s as the Alpha Couple – is staking out a position: ‘I don’t want it / I gotta go find my own way.’ What’s different, I think, is the likelihood that he will actually do so any time soon, and it’s this that makes the song as sad as it is angry, as darkly comic as it’s brightly hateful.

Like the kind of arguments it documents, ‘No Children’ is circular and at times contradictory. For all that they hate each other, these people seem to still be operating as a unit, taking joint action: the singer’s first stated hope is that the couple might collectively alienate ‘our few remaining friends,’ his second that they can work together ‘to come up with a failsafe plot / To piss off the dumb few that forgave us.’ This doesn’t seem to be a situation where one person in a toxic relationship is isolating the other from their friends and family – instead, across the album, Darnielle’s husband and wife ‘are truly partners, one flesh, of one accord, two spirits sailing aboard a doomed ship toward the same bleak end.’ They’ve mended metaphorical fences together before, so there might still be time to save things more broadly, were it not for the clear fact that at least the person singing doesn’t want to anymore. By this point, ‘the night on which the romantic part of the alcoholic marriage sees the last vestige of its romance go up like a puff of steam,’4 the main feeling of which he is capable is a ride-or-die commitment to self-abasement: ‘I hope we hang on past the last exit, I hope it’s already too late.’

Rather than taking an active decision, however, he seems to be fantasising about all the other ways the tension of the situation might finally break: a shaving accident; his spouse ending their stalemate by blinking first; or simply a passive, irrevocable slide ‘down to oblivion,’ the kind he’s picturing for the ‘cars… up on the expressway’ a few songs earlier.5 Similar language appears in the album’s liner notes, where ‘our shared walk to the bottom’ seems to be the embodied enactment ‘not [of] the vows we’d made, but … the ones we’d really meant.’ Perhaps these sound a little like the statements of intent laid out in ‘Old College Try,’ the first song Darnielle wrote for the album6, and which functions as a clear summary both of the destructive pact that drives it, and its inevitable narrative direction: ‘I will walk down to the end with you / If you will come all the way down with me.’

Characters in a Greek tragedy, Darnielle once commented – with reference, of course, to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre – ‘see all these signs that should tell them what not to do, but they can’t read the signs in time to escape their doom.’ This is a worldview where last exits and friends’ interventions no longer carry weight or meaning: ‘the only way they can find out how to read it is by going through the place that will destroy them.’ As the previous two tracks have indicated, for the Alpha couple that would look a lot like ‘this place, with its old plantations,’ and more specifically this house, with its ‘air-thin walls’ and ‘rotting wooden stairs,’ encircled by crows and vultures, and haunted by ‘armies of ghosts.’ As such, it’s a ‘perfect’ location for these people to play out their story to the bitter end: ‘the house plays a big role in these people’s crumble,’ Darnielle told Transition Video Magazine, adding that he thinks of it as ‘the third person in their marriage, because they almost never leave.’

From the album’s opening line, which places us at a window inside the building looking out at its ‘ill-kept front yard,’ the scene is unusually tightly-framed, consciously ‘narrowed’ in focus and observing the classical unities of time, place and action. The album’s microsite, designed by Lalitree Darnielle and no longer active – one of many examples of the steadily-crumbling infrastructure of the pre-platform internet – featured ‘not only a complete floorplan of the Florida house, but notes from concerned neighbors, cryptic excerpts from the husband’s journals, and annotated contents of the couple’s opiate-laden medicine cabinet,’ grounding the project still further in its literal and symbolic location.7 These two errant Californians have ‘run out of land’ and the road that led them here ‘can’t be retraced,’ so ‘something here will eventually have to explode’ – the only question is ‘when?’ ‘Idylls of the King’ asks directly, ‘How long ‘til someone caves under the pressure?’; the answer given in ‘No Children,’ for all of its giddy anguish, seems to be ‘soon, but not yet.’ The worst isn’t over, and the singer doesn’t want it to be: at least for a little while longer, he’s going to repeat the same patterns. In response, even the natural world around him has become unnervingly scripted and artificial: ‘moon stuttering in the sky like film stuck in a projector.’

Not yet ready to find ‘the strength to walk out,’ the narrator turns instead to a more fanciful vision of escape: a burning junkyard, its ‘rising black smoke’ somehow lifting him out of this life entirely and carrying him ‘far away.’ That won’t, or can’t, happen in any literal sense (which doesn’t stop the same image from recurring in ‘Alpha Rats’ Nest’), but the alternative – a life beyond this one, where the two parties each tell their own separate stories of the marriage, he preserving her reputation by lying, she actively encouraged to not even say ‘one good thing’ about her years with him – feels equally, laughably unlikely. The only logical ending remaining is the one that no verbal sophistry, no trick of logic can escape: ‘I hope you die, I hope we both die.’ They will, of course, so after all these failing gambits, you might as well hope for something you know you’re going to actually get. Live performances of ‘No Children’ expand the frame, making it clear that the mutual death-drive is key to its cathartic purpose: ‘I hope we all die,’ John sings, and the crowd sing along, and the perspective shifts from recrimination to renunciation. ‘You’re all coming down with me’ – well, maybe. We’re all going down somewhere, so we might as well sing as we sink.

In 2002, I’m not sure I would have been open to, or particularly interested in, these nuances of meaning, which rely not only on a broader awareness of context but also on some of the accumulating complexities of lived experience, by which I mean learning how relationships ought not to be. Darnielle’s recent interview with Variety, occasioned by the song’s unexpected popularity on Tiktok, admits the dangers of its ‘being gazed upon by a whole bunch of new people through this very narrow lens.’ Interviewer Chris Willman seems especially keen to clarify that the Mountain Goats’ ‘entire catalog is not all about unbridled rage’ – aware, perhaps, that ‘No Children’’s subject matter leaves it open to less charitable framings.

In 2013, a Kickstarter project entitled ‘It’s Complicated: A Feminist Zine on Loving Misogynist Art’ trailered the inclusion of an essay on the song by B. Michael Payne. This swiftly received an exasperated response on Tumblr from Darnielle’s own wife, Lalitree (marriage to whom John has never publicly discussed in less than glowing terms), after which co-editor Judy Berman – a fan of the band who went on to praise Darnielle’s long-standing activism – clarified that the piece would explore ‘how we can instrumentalize art that is not inherently misogynist for misogynist purposes.’ A more recent comment in a Mountain Goats Facebook group asked, semi-seriously, what the difference was between ‘No Children’ and a boomer comedian’s shtick about hating his wife.

Responses tended, logically enough, to emphasise the fictional nature of the material. But the question, I think, stems from what Willman posits as the tendency for people to ‘enjo[y] something like this for the wrong reasons.’ Having previously ‘confronted’ the ‘likelihood that dudes who romanticize their own stalkiness have heard the narrator of “Going to Georgia” run through his schtick and said “I can dig it! He must really be in love, to be so fucked up!”’, and tried since to veer firmly away from such perspectives, Darnielle acknowledges that ‘the artist does not dictate the terms in which his art is understood.’ Although ‘it’s kind of dishonest to one’s characters to force them all to have some redemptive note,’ as he told NPR’s Tyler-Ameen, John began to find it concerning when couples would come up to him at tour shows requesting ‘No Children’ as ‘our song’ in a manner that suggested they were revelling rather too hard in its portrait of the unredeemed. While Darnielle’s performance embodies ‘some of [his] characters’ glee,’ he also therefore situates himself ‘in a position of judgment, trying to make sure that the fact that these are not people you want to be around is clear.’

‘No Children’ might respond to listeners’ desire for ‘a place to safely indulge parts of ourselves that we would never in our lives, or hope not to,’ but unlike ‘Going to Georgia,’ its author from the start has emphasised the distance between that place and somewhere you might find it enjoyable to live more permanently. In this context, the title itself functions perversely as an act of care. Looking over ‘all these lines where these people were saying that they hoped horrible things for one another,’ and having weighed up the ‘many alternate timelines’ he had previously established across the course of the Alpha series, in which ‘sometimes [the couple] say they have children, sometimes they don’t,’ Darnielle came to a definitive two-word conclusion which he wrote ‘at the top of a piece of paper.’8 Expanded slightly, it takes the form of a moral injunction: “No. Under no circumstances do you put children in these people’s lives.”

These exchanges turn on longstanding questions about authorial intent, the presumption of any correspondence between writer and speaker, and the extent to which works of art are obligated to clarify their own morality; discussions about them thus have something of the quality of ‘the greatest thread in the history of forums, locked by a moderator after 12,239 pages of heated debate.’ Darnielle’s response to a 2003 question for VH1 – ‘Does your wife ever look at you and worry?’ ‘She knows I’m just writing for an album’ – would seem to be the simplest rebuttal: these are songs written within the context of a happy marriage, exploring the dynamics of an unhappy one.9 And as Lalitree would have known, her husband had been living with, and trying to distance himself from, these individuals for quite some time.

The song Darnielle was introducing at the Bottle Tree, ‘Alpha Chum Gatherer’ isn’t even on the Tallahassee album as released: as good a sign as any of how firmly these fourteen songs cemented Darnielle’s reputation as a songwriter whose wider corpus fans were drawn to explore with obsessive thoroughness. An unreleased outtake which the band weren’t able to satisfactorily track in their short six days of studio time, the song posed further problems with regard to sequencing and character consistency, as its author explained in Chicago that same year:

This was one of the songs I thought was gonna be one of the big primary texts in Tallahassee but when we went to put it together, it just didn’t seem to fit anywhere. You couldn’t put it after or before anything and have it sound right, it just didn’t play well with the others. It was a little bloodier than most of them, and also it had some unresolved plot points, like “Where did they get the boat?” The whole Alpha stories are full of questions like “How did they afford a car?” – “Did they own or rent?” This song features a boat, and a car. I don’t know where they got them, I don’t want to know where they got them.

As these comments indicate, ‘the whole Alpha stories’ are a project which had been occupying space in Darnielle’s head for a long time, before even switching his primary creative focus to music: ‘they were what I was doing before I was writing songs.’ Working on a sequence of poems called ‘Songs from Point Alpha Privative,’ Darnielle came to the regrettable realisation that ‘nobody wanted to read any poems’ and began putting chords underneath them: a project which, in one telling, ‘gave birth to the Mountain Goats.’ In an interview with Joseph Fink, John theorised that ‘ultimately all of a person’s work is in conversation with previous iterations of it, because you are probably chasing down some ideas, that if you could resolve them, you’d be free of the desire to make the work.’ Or, as Darnielle’s speaker puts it in ‘Alpha Chum Gatherer,’ ‘when I crack that secret code / It’s gonna lighten my load.’

Something like this is clearly what these two characters – a pair of Southern Californian alcoholics whose marriage is in continual crisis, and who bore at least a passing resemblance to his own parents – represented in the early years of his recording career to the young songwriter, who soon began to find that his work exploring their turbulent relationship made ‘real connections … especially with people who had in some way been touched by divorce.’ This may, in turn, have become a kind of feedback loop: discussing with Fink the experience of people first starting to pay attention to your work, Darnielle notes, ‘you probably put a pin in the one that got you the charge… That’s an inevitability. The one that then somebody says “Hey, give me more of that!” – I mean, for those of us who like to perform, that’s cocaine, right?’

Between 1991 and 1995, Darnielle performed and recorded at least seventeen songs which returned to this particular wellspring.10 Derived from (what else) a misunderstanding of Greek grammar, the consistent use of ‘Alpha’ in their titles was intended to send a certain signal flare: each of these compositions would be ‘keyed towards the issue of separation and loss.’11 But if this naming convention helped the author keep track of his ongoing attempts to solve a problem, they also helped each title stand out and joined them together like red strings between the points on a detective’s corkboard. Knowing that the songs interrelate piques the listener’s interest in hearing more of them. The singer of the first one committed to tape, ‘One Winter At Point Alpha Privative’ on Taboo VI: The Homecoming doesn’t get an answer to his needling questions, all of which are also the kind of thing a reader might ask themselves at the beginning of any extended narrative: ‘What the hell kind of deal is it here anyway? / Like how much does it cost and how long should we stay?’ There’s no response to the third one either –‘Do I have to hang on every single word that you say?’ – but if we want to know what happens next, we have to do just that.

As Alex Russell notes, the song’s interrogative insistence is something you feel ‘nervous to listen to, like an argument you aren’t involved in and shouldn’t be hearing.’ Which must have made it all the more compelling, if you were one of the select band of people who’d bought the first cassette when, on the artist’s next tape, you saw the titles ‘Spilling Towards Alpha’ and ‘Alpha Negative,’ and realised you were overhearing them again, that this time somebody was ‘sharpening’ his or her ‘claws,’ and that less than three minutes later, one of them was making the other ‘drink poison.’ By the point of Zopilote Machine, when our hypothetical Californian cassette collector (we’ll call him, for the sake of argument, Don Krall) could have witnessed the Alpha characters coming back again and again for more of the same at least eight times, a fair question might be something like ‘Who are these people?’ As John told Luna Kafe:

once they got into the songs they got harder to control. I love it when characters sort of start gate-crashing their way into my songs, though, it’s hilarious to be working on a song and then suddenly say to myself “Wait a minute...whose song is this? Oh Christ, it’s those awful Alpha people again, I hope they haven’t gone and hurt anybody yet.

Equally hilarious is a line on Tallahassee out-take ‘Ethiopians,’ first heard in a 2007 radio session – by which point, if Mr Krall had been avidly following Darnielle’s career into the heady days, first of CD releases and then New Yorker profiles, he’d have encountered those same people almost twenty times more, and he might well be wondering if he’ll ever truly hear the last of them. In the resurfaced song, a couple who drink and fight constantly, and who would seem to be frequently playing acoustic reggae covers, declare themselves ‘suspicious of the people who’ve just moved in next door.’ Where do these two get off? you might find yourself asking. Then you realise that if they had more self-awareness they wouldn’t be in this situation in the first place, still together, still behaving like this; reappearing (again, as a unit) to rub their friends’ faces, and by extension ours, in ‘the ugly fact’ that they are ‘still alive.’

Darnielle’s comments about the series imply that its resurgence in his writing in 2001 felt pretty much like this even to him – indeed, a certain frustration at their inability to learn and grow seems to have been a long-standing element in the songwriter’s relationship to these characters. Around 1994, it had ‘gotten really painful to write about them,’ a pain akin to ‘doing harm to someone I know,’ and their creator ‘couldn’t take it anymore.’12 By this point the couple had already fled ‘across the country, trying to sort of escape the ghosts that are actually living inside of them. That was why I stopped writing about them, because when they got down to Tallahassee, I really felt like they got kind of raw.’

But in trying to escape them, the Alpha Couple became ghosts of their own: ‘alcoholic zombies who break in through the front door from time to time to update me on their condition.’13 Faced with the opportunity to go into the studio with 4AD, Darnielle started wondering, ‘What kind of songs would I want to sing?’ and the impulse that grabbed him was not to embark on a wholly new project, but to finally lay an old one to rest: ‘immediately it was like the Alpha couple, these two people who used to haunt my songs a few years back, were there, sort of jumping up and down and saying: “We’re still here! Hello hello!”’ ‘Hauntings’ can be especially scary, John told Mother Jones, in that they evoke ‘the notion that there are things from the past that render, that you can’t wash out, that you can’t be free of.’

Tallahassee, then, for all that it constitutes a step forward in the Mountain Goats project, is also an attempt to close a chapter, to make a definitive statement in a particular mode about a particular obsession which its author had been wrestling with, I think it’s fair to say, since the earliest days of being conscious of himself as a person, the child of fighting caregivers. How and why can two people who say they love each other still hurt each other so very much? The album offers, if not a safe space, then at least a confined one in which to explore some of the answers to this question: Darnielle’s sharp temporal and geographic focus aimed ‘to give them a kind of dignified place in which to drink and fight and try to learn to love each other right,’ which might also allow ‘the gentler moments of their time together’ to come out.

These people loved each other once – he saw her coming through the screen door on the second floor, up on the balcony, for heaven’s sake – and sometimes they still do. When they’re not yelling at each other, which isn’t all the time, they’re ‘trying to recapture something they can’t get back and they know that and they’re sharing that pain.’ [VH1] Though they might ‘squander’ every chance they get, the house they buy in a cheap part of town ‘out past the tracks’ is a physical manifestation of one last bit of pig-headed hope: ‘“Here we are, we’re married, and we bought a house, right, and so here we are, so we can do this.” They can’t do this. But they want to. And so the album is about the fact that they want to.’

The simplicity of that statement goes some way to cutting through the tangle of narratology surrounding Tallahassee: an album which, while multiple competing versions of its backstory circulate, could never definitively tie up the ‘loose ends by the score’ which trail into the house with our protagonists, whose ‘shared paths’ are already ‘unravelling behind them like ribbons.’ In musical terms, the studio setting offers the Alphas a shiny-ish reboot, but as that first-written, recalibrating song title suggests, this is no fresh start, but an old college try, a final push to get something over the line. Even the album closer is written in the future tense, imagining ‘the flames that will rip through here’ – an event which might, some day, actually happen, but about which the author himself is fairly non-commital:

This song is about a divorce, uh, it’s about a couple of people who have decided … to make a great conflagration of the end of their relationship instead of sort of a little bad feeling that they go away into their own separate corners to share, to do it together, to tear everything down, brick by brick and stone by stone until there’s nothing left and then presumably, uh, to perish in the flames with one another. We don’t really know. This is the last we see of them.

Burning a house down and a divorce are not the same thing, but this introduction seems to imply a fuzzy line between them, as if finally it isn’t for him to say whether these characters live or die, as if their voices come ultimately from somewhere outside his own head. Setting up ‘Alpha Omega’ in 2013, Darnielle calls it the last in the series chronologically, and adlibs new contents for its ‘note on scented stationery’ – ‘Goodbye, John.’ I’m sure, in some way or another, he’s heard from the two of them since, but these songs are the two best-evidenced endings of the series. As Darnielle says of ‘Rats Nest’ though, ‘this approach in real life wouldn’t really work but that's why it's a song and not a practice.’

And yet its roots lie partially in a practice which I’ve already discussed at length: early lyrics featuring the couple were written without an external storyline beyond ‘the bare bones,’ allowing for ‘surprise’ on the part of their composer. ‘The whole thing was supposed to be about them moving up to a divorce, but then they didn’t get a divorce. Uh, she just bailed,’ Darnielle comments with regard to ‘Alpha Omega.’14 Not only were they not written in order, they were also consciously released out of order, ‘Omega’ before ‘The Alphonse Mambo.’ Any attempt at reassembling the chronology is thus post-hoc and littered with stumbling blocks: the car, the boat, ‘our three daughters.’

There are, however, similar overlays and clashes in the stories of Robert Aickman, whose influence on Darnielle’s narrative style I explored two episodes earlier, the cumulative effect of which is a disorientating, fractal approach to character and situation. Identifying some of the direct influences on his own approach to the album, John spoke of wanting to ‘sort of mix Argento with, say, Raymond Carver since I think that’s how we experience traumatic events personally. This is where I’d start to contend that horror kinda is realism if I were feeling argumentative, but yeah – I think a realistic portrayal of an exploding relationship is more likely to resemble a Hammer Horror film.’

It’s possible to imagine a Tallahassee, and a Tallahassee press cycle, which tidies up the narrative more than the album as released, which makes it equally clear that this that was never really the point. ‘Whatever we can’t hold, we hang on a hook that will hold it,’ writes Leslie Jamison. That’s what I think about Tallahassee: it’s a space to put something, and to seal it off as far as possible in ‘this house like a Louisiana graveyard, where nothing stays buried.’ As much as the record constitutes a new lease of life for the Mountain Goats, John’s recent comments to Variety place its subject matter squarely in the project’s past with ‘unrequited love or relationship passion’ listed among his key themes ‘prior to ’99’ (which further frames the Alphas’ 2001 reappearance as an uncanny reanimation) and more self-reflective material following afterwards.

‘Alpha Negative,’ the singer told an audience in 2014, feels like it was written ‘by a very different person’ from the other songs in the set that night, one who ‘had a little more death in his heart than the other one we’ve come to know.’ ‘A little more’ meaning, I think, that a little remains (‘I have [these characters] inside me,’ Darnielle explained to Tyler-Ameen, ‘for the rest of my life’); that something like death in the heart doesn’t go away entirely, even if you work to find more effective ways to expel and turn the volume down on ‘ghosts, old ghosts.’ Which is to say, of course, that since deciding I didn’t care about determining a conclusive chronology for the Alpha couple, I’ve become fully obsessed with ‘Design Your Own Container Garden.’

A quiet, reflective B-side to the stomping ‘See America Right’ single, there’s a popular fan theory that claims ‘Container Garden’ as the true conclusion of the Alpha narrative – based not, as far as I can tell, on any particular nuggets of Darniellean exegesis, but on the striking melancholy, fragility and finality of the song itself. Though John’s yearning arpeggios and hushed vocal have Peter Hughes’s bass to widen them out, the song has a singular loneliness. Like ‘Alpha Omega,’ it’s told from the perspective of one person, seemingly alone. They’re driving to Pico/Crenshaw: an intersection in Los Angeles where, as Alex Russell describes it, there’s nothing much of note, ‘but the specificity helps us picture that this corner matters. We have those in our lives, too.’ The singer is back on the West Coast, where it all started, and thus outside of the frame of Tallahassee as an album. They are surprised at how quickly this kind of driving comes to feel natural: ‘I took to the highway / The highway took to me like a second skin.’ There’s another turning in the second verse, which sounds as if it could be motivated by nothing other than an attraction to beauty (something we haven’t heard a lot about on the album either): ‘I took the low road / Where the light was just right.’

What isn’t clear is whether that road leads to, or away from, ‘the crater’ mentioned at the start of the verse where our solo traveller is leaving sentimental ‘trinkets,’ which may or may not be the same place as the ‘glowing, all-embracing wreckage’ in which this person has been crawling ‘sunburned and snowblind.’ But then all these physical details sound more likely to apply to, for instance, a burnt-out shell of a house in Florida than to California, where they’re driving now – so perhaps there’s no real crater, no real wreckage, after all, only a ‘space we left behind,’ which could be in either state or neither; forty miles from Atlanta; in the middle of nowhere, anywhere. Because really it’s only the space that matters, and the fact of leaving it, whatever was there for you, knowing as you do that some part of you will still be digging around in that rubble forever.

I feel like all I’m concluding is that maybe the one true final Alpha song was the friends we made along the way, but what I mean is this. With a narrative left deliberately open-ended and only semi-canonical, taking stock of the Alpha project and the note that it ends on is, for the listener, ultimately an individual choice. Novelists like Dickens and Lawrence published versions of the same material in different editions with alternate endings, and I can’t see a clear dividing line between that and Darnielle identifying this song or that as ‘the last’ at different historical points in his live shows and interviews.15 We can’t all be Don Krall, and so the chronology of encounter carries more weight than the chronology of release: most of us heard most of these songs backwards anyway, starting with ‘No Children’ and working our way through the series and what it meant to us in whatever order our interest in the work and the courses of our lives dictated.

‘Design Your Own Container Garden’ sounds, to me, like the last Alpha song because it sounds like somebody letting go of something, recognising the fact of its pastness as if for the first time. Alex suggests that that the title might have something to do with the couple being ‘uprooted’ from California to Florida; I wonder if the movement could equally be in the other direction, as a figure who’s learning to live alone, perhaps for the first time as an adult, starts to look for ways to find beauty in their life. Taken this way, it might resemble the closing line of Voltaire’s Candide (one of my French A-level texts in Bourne), il faut cultiver notre jardin, which the novelist Julian Barnes glosses as ‘a philosophical recommendation to horticultural quietism,’ a retreat from the conflicts of the world into a private space of care and nurture. Once a space has been excavated, who’s to say what could grow in the earth turned over?

But it probably mostly sounds like that to me because it’s probably the last Alpha song I got around to paying close attention to, the one I heard when I was oldest, if not wisest, and so the point at which it felt like the project, and the states of feeling it was created to explore, was starting to look like a space it was possible to leave behind. If nothing more, it surely formed part of a similar process for Darnielle, who toldVariety that after 2002, the year of ‘me putting this collapsing-marriage couple to bed’ – and, hopefully, to a quiet sleep – his work became ‘more interested in how people reckon with’ the ‘former selves’ that ‘tend to rattle around’ inside them.

That’s the case, of course, for all of us. The snap-happy tween in the fake Offspring hoodie is the writer and lecturer composing this email. I completed my PhD in 2017 – the same year as Dexter Holland, singer and guitarist for the Offspring, who returned to his research in molecular biology at the University of Southern California after a twenty-three year hiatus. Holland’s thesis looked at interactions between human cells and the HIV virus – the ‘terrible disease’ which in the late 1980s claimed the lives of ‘a whole host’ of the friends John Darnielle had made at the City Nightclub in Portland, Oregon. An all-ages gay club, the City welcomed ‘kids who had no place else to go’ – one of whom was a ‘completely lost’ 18-year-old from Claremont, California, who’d gone in six years from Heart to heroin, and who learnt within its walls at 624 Southwest Morrison Street ‘that it was OK to be who I am’ at a time when, as ‘You’re in Maya’ makes clear, the most appealing place he could imagine being was ‘nowhere.’

These years, and the complex feelings bound up in Darnielle’s time spent with this group of friends who mostly ‘didn’t make it out of the 80s’ under Reagan’s mismanagement of the AIDS epidemic, would be the focus of his next album, 2004’s We Shall All Be Healed. I’ll write more about these songs, which inaugurated a new, overtly autobiographical phase of the Mountain Goats project, when the newsletter returns next year. But to get there, of course, I need to bring this post to a close, and I’ve been struggling with how to do so – how to find something to say about ‘No Children,’ about my own experience of love and marriage, which strikes the right note, which ends on a conclusive chord. That’s difficult because I don’t have any answers – because I’m learning more about it every day, as hopefully we all are – but this is what I’ve got so far.

I got married seven months ago, in a bare bones registry office service, in the middle of a global pandemic, and what I can tell you is that even if readings or music had been allowed, we wouldn’t have had ‘No Children’ playing at the reception. When I stood there, in my new suit, looking at my beautiful wife in her pink dress and flower crown, there were tears in my eyes and a break in my voice, and there was no distinction between the vows we made and the ones we really meant. I had my parents in the room as witnesses; Sydnee’s father passed away when she was young, and her mother was working as a nurse in a Texan care home in a COVID unit. She’d moved halfway across the world for me, an act of staggering faith and bravery, and I hoped – hope every day – that she was happy with her choices. Here’s a picture of her getting me to look at some blossom, which I hope will show you something of the essence of her spirit.

And maybe hope, after all, is what I want to end on, since it’s by its nature forward-facing: here are two people at the beginning of their lives together, hand in hand, in the first stages of building a future: me, and you. It’s there in the words we speak to each other in the morning – I hope you have a good day – and the evening: I hope you like the meal I made. I hope we make more, and closer friends; I hope they come round for dinner more often. I hope people continue to be impressed, astounded at the amount you know about trees in the volunteering you’ve started doing; I hope you get the kind of job you want and deserve, a new direction for a new life. You hope my students like the Ursula LeGuin story you recommended me; I hope we can make it to Texas in the summer to do it all again with your family watching. I hope when you think of me years down the line, I’m in the armchair across the room from you, and you’re asking me ‘Is the new Jeopardy up yet?’, and cursing the people who upload it to YouTube in the wrong aspect ratio. I hope I try, and tell everyone ours was a good life, and mean it. The other day, as people in their thirties do, we took delivery of five large bags of discounted soil, for the vegetables you’re planning to plant outside. I want to stand in the kitchen in the springtime – window facing a well-kept back-yard – and watch the things you’ve tended bloom.

This week, Richard is getting into MasterChef: The Professionals. Lot of lovage this year.

None of the artists concerned, of course, would have made a penny from this unofficial merchandise: the text might as well read ‘The Knock-Offspring.’

I’ve changed the name, obviously, for the purposes of this newsletter.

Peter Coviello, Long Players: A Love Story in 18 Songs. Penguin, 2018.

Which is itself a bit of wilful hyperbole – from Southwood Plantation Road, the nearest audible main drag is probably the Apalachee Parkway, so they might as well be heading to Taco Bell.

Article on Tallahassee by Jim Fisher for Salon.com, archived here: https://www.scribd.com/document/52894439/tMG-Interviews. All further interview quotes without hyperlinks (e.g. Kaufman, VH1) are taken from the same document.

2003 VH1 interview with Gil Kaufman.

According to Kyle Barbour’s ‘Annotated Mountain Goats’ website, which includes the following songs without ‘Alpha’ in the title: ‘Going to Dade Country,’ ‘Star Dusting,’ ‘Wishing the House Would Crash,’ and ‘Fit Alpha Vi,’ which reputedly has its roots in the first Alpha poem written and was released by the Extra Glenns as ‘Twelve Hands High’ in 2002, the same year Tallahassee came out. ‘Alpha Double Negative: Going to Catalina’ was re-recorded in 1996. ‘The Alphonse Mambo’ and perhaps ‘Letter to a Motel’ are the only ‘new’ Alpha songs I’m aware of which saw daylight between ’96 and 2002.

The cool beans! #4 interview with Matt Kelly, 1994.

Kaufman, VH1.

Interview with Leah Weathersby, Amazon, 2005.

Interview with Michael Weiner for KJHK-Lawrence, 1997.

If ‘Alpha Omega’ had been suppressed, that would be one thing, but the opposite happened: just two years before the likely writing of ‘Rats Nest,’ ‘Omega’ was re-released. Here I mean ‘opposite’ in the joyfully gnomic sense in which the author of both told Joseph Fink that ‘the opposite of a ghost’ was ‘an angel,’ but when you find yourself asking ‘Is “Alpha Rats’ Nest” to “Alpha Omega” what “Younger” is to “No I Can’t”’ in the manner of an 11+ verbal reasoning test, you should probably log off and think about something else for a while.

Share this post