Folk songs like to gather people together. ‘Come all brother tradesmen that travel alone,’ sang Steeleye Span, making a standard out of the 18th century ballad ‘Hard Times of Old England.’ ‘Come gather ‘round people wherever you roam’ - that’s Bob Dylan in ‘The Times They Are A-Changin’’. ‘Come on in, we haven’t slept for weeks / Drink some of this, it’ll put color in your cheeks’ - I’m sure I don’t need to tell you where that’s from.

The forthcoming Mountain Goats album, Jenny From Thebes, fleshes out the setting of ‘Color In Your Cheeks’: a house in Texas which has become a gathering point, a place of shelter, for the world’s needy and dispossessed. Darnielle’s band is far from a traditional folk act - though his first experiences of teaching himself guitar chords took place at the hippie-ish Claremont Folk Music Center, where the instruments hang on the wall between the kind of miscellaneous masks you’d find in an anthropologist’s faculty office. But he told one early interviewer that his vision for his music was aligned with ‘earlier English and Irish songs—what are now drinking songs but were folk songs,’ managing the difficult balancing act where they ‘touch an emotional chord, yet remain sort of light.’ To another, citing Leonard Cohen as an example, he observed that ‘there really is a lot of good folk music,’ even though ‘no one wants to sit down on people’s carpets and wear sandals.’

And his own work has long been attentive to the importance of creating connection. In his interview with Akao Mika about Get Lonely, Darnielle described his own experience of feeling lonely on tour in a hotel room, before noting: ‘many people have also felt lonely in this room. Feeling empty, like an outsider, you know?’ And like the quiet house he first imagined some twenty years ago, a community has grown up around the Mountain Goats which is widely known for making ‘its welcome clear’ to those who have, for one reason or another, found themselves feeling out of place in the world.

Professor Barry Sanders, who taught Darnielle as an undergrad at Pitzer College in the early 90s, thinks this communal ethos is inherent to how his former student sees his music. When I interviewed him last summer, at a table outside Sterling Coffee Roasters in Northwest Portland, he told me about the real mountain goats that can be found in the San Gabriel Mountains that rise to the north of Claremont: ‘They’re communal. They’re a family, you know? And that’s how I think John feels about his music - it’s not me doing this, I’m in a crew of people … I’m always grazing with somebody, you know?’

Darnielle’s first performances as the Mountain Goats, came at the Grove House open mic on the Pitzer campus. He’d drive there after his nursing shifts at the Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk, on Sunday nights and later on Tuesdays, with his ‘cheap-ass three-quarter sized Kima guitar,’ and as he puts it, ‘amuse the shit out of himself’ by announcing himself in the plural. Originally, in a live setting, it really was just him, though Rachel Ware - who, along with the rest of the Bright Mountain Choir, John had known since childhood - would soon join the singer to add bass and harmony vocals both onstage and on record.

Even when the other four singers (Rachel, Amy, Sara and Roseanne) didn’t appear, for Darnielle the idea of the band as a ‘five-person unit’ was always central - you can hear him use this phrasing in the earliest surviving video footage of him and Rachel playing together, filmed in the Netherlands in 1995. ‘Without those four I'd be completely lost,’ he commented: ‘I may write my own songs but without the influence or input of my close friends, my girlfriend, there would be no songs, nor would there be anything to write about.’ Centring the self was part of the issue. ‘I don’t want what I'm doing to be thought of as singer-songwriter stuff [which uses] a different set of criteria I never intended to follow… For me to say this is John’ struck him as ‘vanity of a really obscene order.’ That position arose at least in part from the negative tropes associated with being a 1973-style folky singer-songwriter like James Taylor, ‘in bell-bottoms trying to get women at a party.’

Peter Hughes, in these days, was another regular in the music scene centred on Munchies, a DIY venue which Shrimper’s Dennis Callaci had got going in the back of a Pomona sandwich bar. Total strangers, the men bonded over their enjoyment of each other’s sets in this high-energy, small-scale scene where, over time, ‘everybody played with everybody else.’ And over the past three decades, for two of which he’s been a full part of Darnielle’s band, the pair’s long, nurturing friendship has clearly factored into the songwriting too: how could it not? When the two men shared a room on tour, in a Holiday Inn Express outside of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, Peter went out to ‘the only thing nearby’ - the King of Prussia mega-mall - and came back ‘looking like he’d seen a ghost, he was so unhappy.’’ The reason? ‘Somebody saw the beautiful Pennsylvania countryside and said ‘I know: let’s build a shopping mall you can see from space!’

Peter’s complaint found its way into his bandmate’s composition process later that day: wanting to evoke a sense of great distance in ‘Woke Up New,’ the phrase John reaches for is ‘an astronaut could have seen the hunger in my eyes from space.’ ‘Maybe Sprout Wings,’ meanwhile, ‘was written while Peter was in the shower’: John semi-jokingly attributes ‘its dark mood’ to the fact that ‘I missed him so much.’ The image of the astronaut, at the heart of this apparent portrait of isolation, is still ultimately about being seen, about there being someone up there looking down on you - perhaps in part because it derives from a genuine moment of personal and artistic connection.

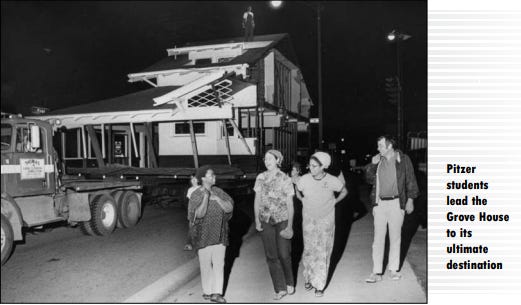

But twenty years before all this, The Grove House itself was also testament to a huge collaborative effort. It was one which Barry Sanders personally spearheaded, when he came to Pitzer in the early 70s to teach, among other classes, a first-year English course on ‘The Arts and Crafts Movement in America.’ Rather than ‘the usual final examination or term paper,’ Sanders found that his students ‘wanted to work on some project that would connect more closely’ with the period itself, ‘something “hands-on” and, if possible, of real public service.’ One idea that emerged was ‘moving an old house, preferably a house from the Arts and Crafts period, onto campus to use as a student center’ - a building where ‘students could relax, play guitars, hold meetings, small dances, poetry readings and have a retreat from the pressures of studies.’

Amazingly, that’s exactly what happened. This is the final assignment for a first-year module we’re talking about - can you imagine the forms? There were, of course, a few setbacks along the way: the cost of disconnecting low-hanging power cables when moving the two main sections of a dismantled craftsman bungalow through Claremont’s streets proved especially prohibitive. In a pamphlet you can download from the Pitzer website, Sanders gives a typically modest account of the solution, which nonetheless sounds like a Laurel and Hardy caper. The professor contacted the operators of the Santa Fe Railway and convinced them to allow the pieces to be moved ‘at least part of the way down the railroad tracks in the dead of night’ without any delays to service. He has no idea why they believed him.

The day of the move came on Saturday July 16th, 1977. Here’s how Barry paints the scene: ‘at around 1:05 AM, with music and food and a small procession of fairly loud revelers’ - including many of his own original students - ‘the house made its way to campus. President Atwell led the parade. One half of the house made its way down Cambridge Avenue to Bonita Avenue, then headed east to Indian Hill Boulevard. Crews from Southern California Edison and General Telephone raised the wires ever so slightly as the house rocked and rolled from side-to-side, creaking down the sleepy streets.’ That same section of the house - I’m not making this up - eventually headed north on Mills Avenue, though there was little opportunity for roaring engines. According to the Claremont Courier, ‘it took ten minutes to cut through each of four barricades recently installed on the street’ before ‘the house was pulled by a winch up to its new location near the bell tower at the north side of the campus. The move took just under five hours.’

It wasn’t completely plain sailing from there on out, but after a series of complex legal and financial wrangles, the Grove House opened to its student users in February of 1980, with a folk music concert and a reading in the Bert Meyers Poetry Room, where Pitzer students could sit ‘on one of several Morris chairs’ and leaf through a few slim volumes. The center also contained a small women’s studies library, with a ‘splendid view of mountains,’ and a restaurant initially run by the professor’s wife Grace - they’d met at The Health Department, a vegetarian restaurant which Barry had opened in West L.A. after being fired from a previous institution for participating in a student anti-war protest. The couple gifted the Grove House a ‘wonderfully ornate, old Italian, brass espresso machine’ from their previous venture, and Barry personally ‘taught a group of students how to refinish and repair all the furniture’ the project acquired.

The Grove House is surrounded by a citrus grove and drought-tolerant gardens lined with golden barrel cactus, palms, and yucca plants. Inside, it was conceived as ‘one large living room,’ with the twin values of careful craftsmanship and hospitality at its heart. Last September, at Barry’s suggestion, I went to see it - but with no real plan for how to get in. Shielding myself from the blazing light, I sat on a bench near a chicken coop - installed during Darnielle’s time at the college, in 1994 - and listened to the chatter of the Northern mockingbirds which had started to descend en masse all around me.

There were a few current students sitting on the building’s verandah, and eventually I went up to them with what must have been an unusual opening gambit. I’ve come all the way from England. Barry Sanders sent me. Have you kids heard of the Mountain Goats? It was hard to tell if they were just being polite when they said yeah, I think so, to the last part, but they happened to know the student caretaker - a Political Studies major named Max Sweeney - and if I wanted, they could give him a call.

True to the welcoming community spirit with which the Grove House was founded, Max turned up a few minutes later and gamely gave me a tour of the building. He was living there as part of the position, and in a turn of phrase which I’m sure would have charmed Barry no end, told me he thought the ‘shabby chic’ interiors were pretty cool. I took in the ‘heavy, solid, natural substances’ which the building was composed of: the warm wood, the antique light fittings, the finely carved chairs laid out in cabaret seating. There were a few instruments against the wall in the corner of the main room. That’s probably where people would play when there was an open mic in the space, Max thought. Well, when in Rome…

As Matt Nathanson, who hosted acoustic nights in the space in the early 90s, tells it, there may have been as few as six people there when John Darnielle first turned up play one, but even at this age his classmate exhibited an ‘unbelievable confidence.’ The song he played made Nathanson cry, so naturally he encouraged John to play again next time. Every week from then on, he’d write a new song just for the event, each of them capable of moving Nathanson ‘like someone hit me in the fucking face.’ At the time, as John later wrote on Twitter, all he did was give Matt ‘grief for how much he liked U2,’ but in more recent years he’s credited these low-key evenings as the reason ‘the Mountain Goats as you know them exist.’ After a few years promoting Nathanson’s albums ‘to help me atone for my hater phase,’ John even invited him to sing back-up on Jenny From Thebes.

In 2006, Nathanson also organised - and played the support slot - for a gig which saw Darnielle return to Pitzer (not, alas, in the same campus venue, but the newer Gold Student Center) and perform a few songs with his old bandmate Rachel Ware. Not long after the show itself, I remember listening to the bootleg online, through the Mountain Goats forums which I’d recently joined (on April 15th, according to the profile I can regrettably still find.) This wasn’t quite as finely crafted a space as the Grove House, but still functioned as a hospitable living room in its own way, if you brought your own espresso.

At this point, the singer himself was still an active participant in the forums he operated: part of the generation of college students who’d got online in the ‘eternal September’ of the mid-1990s, he’d cut his own teeth as a critic on specialist music boards like Hipinion and I Love Music. A ‘longtime tape-trader supporter,’ John also permitted an active culture of sharing live tapes in the space - like the recordings of the two-day ZOOP! Weekender, in July 2007, at Farm Sanctuary in upstate New York, an event which almost no one I’d ever met in real life would have given a solitary shit about, and which to me was basically Woodstock.

The forums’ permissive, coterie atmosphere made it easy to go deep into the world of the Mountain Goats, and I’d done so without hesitation. Along the way, I discovered not only fierce live versions of the songs I already knew and loved, but the band’s deep catalogue of rarities and one-off performances, as well as demos and outtakes which Darnielle shared here with the fans directly. Now that the Mountain Goats were a fully-fledged studio project, with everything that meant in terms of formalised album release schedules, this space offered a channel for the kind of immediacy Darnielle’s earlier work had privileged. Perhaps that sense of connection gives the songs distributed in this time period, in this distinctive context, an additional sheen, but many of them still seem essential to me today. ‘Surrounded’; ‘Sign of the Crow 2’; ‘Wizard Buys A Hat’: hidden gems, all, and names to conjure with, if you only needed to conjure enough people to fill a mid-sized minivan.

‘I make myself available to people who like my stuff, and I'm open with them; it's one of the things that makes me different from other music dudes,’ Darnielle posted around this time. But even an artist generally committed to accessibility - a fairly common Gen-X response to the cult of the rock star - could find himself disturbed by the voraciousness of an audience increasingly accustomed to finding everything they wanted for free online. Users requesting links to Hail and Farewell, Gothenburg - a set of songs not intended for release which had been taken from the artist’s hard drive without his permission - on a forum Darnielle himself was hosting, as he pointed out to one particularly pushy user, was not only ‘an invasion of privacy,’ but just ‘really uncool.’ The refrain of ‘Hello Old Rabbit’ - one of the few Gothenburg tracks to regularly get played live, and thus identified as ‘fair game’ for sharing - seems particularly apposite: ‘I did not come here to suffer.’

In 2007, I was preparing to apply to study English Literature at university, and thinking seriously for the first time about the complex conversation surrounding writers’ archives - one which the age of the internet was already fundamentally changing. Learning that volumes of unpublished material by poets like Byron and Larkin had been consigned to the flames initially struck me only as cause for sadness. But by this point, in indie music circles, anonymised peer-to-peer file-sharing was inevitably disrupting the delicate relationship between cult artists and collector fans. The rise of YouTube as a distribution platform for music was also beginning to trouble the very concept of ‘rarities.’ If a non-album song, shared in a curated fan space with the artist’s permission, is uploaded by one of those fans to a video streaming service for similarly passionate listeners to find within seconds of searching, at what point does the term ‘unreleased’ cease to be useful?

John’s forum posts, however, made it clear that at the heart of these debates were real human beings with their own legitimate wishes, including what’s since been referred to in cases relating to our digital footprints as ‘the right to be forgotten.’ In 1996, he and Rachel Ware recorded the beautiful ‘Then The Letting Go,’ a song taking its title from Emily Dickinson. In more recent years, however, the publication of Dickinson’s poems had come to seem a sufficiently ‘fraught case’ that he no longer felt comfortable reading them. The example of Franz Kafka bothered him in particular, as he made clear in a spiky Twitter exchange in 2015 about the decision taken by Kafka’s friend Max Brod to posthumously publish works whose author had asked him to destroy them: ‘Max sold him out, Max Brod Hate Club forever […] any “masterpiece” without consent is shameful to read.’

Clearly, Darnielle too finds this a fine line to walk: discussing his own obsession with Syd Barrett in a footnote to a buried blogpost, he satirised an impulse his fans know well: ‘For years we’d wondered what might lay gathering dust on some London studio shelf or in a Cambridge bedroom — what hidden treasures, what lost masterpieces? When sub-par material is unearthed, there’s hope for us: perhaps someday we’ll learn to enjoy what we have and stop losing sleep … perhaps we will stop digging through the endless morass of the internet trying to find Joy Division bootlegs we haven’t heard yet. (There are none.)’ But as for his own work, by 2021 Darnielle had come to believe in ‘destroying your entire archive before you die, and personally arranging anything to be released posthumously beforehand. Any other approach will result in ghoulish exploitation with really weak self-serving justifications.’

Today, I’d like to talk about just one semi-hidden treasure which Darnielle, thankfully, chose to release: ‘From TG&Y,’ which captivated me when I first heard it with its escalatingly desperate refrain: ‘Hang on to your dreams 'til someone makes you let them go … Hang on to your dreams 'til someone beats them out of you … Hang on to your dreams until there’s nothing left of them.’ The song takes the listener back in time to its author’s adolescence in Claremont, and what Darnielle described as ‘the wreckage that I was when I was seventeen.’1

Live at the Gold Student Center, Pitzer College, Claremont, CA, on 12-02-2006.

The forces threatening his dreams at this age, when he was, as he put it, ‘not an abuse survivor yet, ‘cause you’re in the middle of surviving it’ - were degrees of magnitude beyond than anything I’d faced, but as the singer told Rolling Stone in 2015, ‘I would never want to write about stuff I don’t feel everybody can connect to. If I’m writing about dope, not everybody’s into dope, but everybody knows what it’s like to feel desperate.’ Every late-teenager growing up anywhere outside of a major urban centre certainly knows this feeling: ‘One more night in this town’s / Gonna break me I just know.’ It’s a spin on the idea of making it ‘through this year if it kills me’ for anyone who can’t wait to get to where the action is, and if there was any year in my life I felt most forcefully that I needed to make it through, it was this one: the final push before getting out of Lincolnshire, out of secondary school, and into the world.

It’s not as if my own dreams were even especially intangible: the cultural and creative transformation I imagined going to university would bring was really just around the corner, but perhaps this proximity only enhanced the frustration of the current part of my life not being over yet. But if you’d have told me that at the time, I doubt I’d have listened. Reflecting on his own days as a young, snarky music reviewer, John Darnielle told Vulture’s Craig Jenkins: ‘There’s not a young man I know who had a minute for anybody else’s opinion.’ He’s diagnosing the exact kind of scornful arrogance that made me copy out mean lyrics onto my school planner, like ‘I bet you don’t know how to spell contradiction / I bet you don’t know how to sell conviction.’

These lines - not by the Mountain Goats, but Idlewild, of all people - spoke all too clearly to the kind of young man who still thought none-too-secretly about things like spelling and grammar as a mark of moral character. This was the same year that we were learning about prescriptive and descriptive ways of analysing language variation in my English Language AS-level. Also on the curriculum was the role of language in discrimination: I brought home to my grandparents’ house a survey a classmate had designed about changing terminology, which my Nan dutifully filled in for me until my firmly anti-PC Granddad discovered it, determined it was ‘mind control,’ and refused to have it in the house. I knew how to spell contradiction, all right, but not how to recognise it in myself and my circumstances - and I’m not sure I would have known what convictions I had to sell.

Nonetheless, as Darnielle noted drily to Tom Breihan for Stereogum about his own time in the trenches on the pre-social media music forums, ‘we all posted very intemperately in those days.’ I certainly did, and not only on the tMG forums: I wrote a dramatic blog post, which might even have been public, about my own desperate sixth form sentiments on a site titled for a Harvey Danger lyric - ‘Revolutionary Grammar’ - and I’m beyond delighted to find that it no longer exists. ‘From TG&Y’ was spared this treatment, but I still found a way to slip its closing line into a mock-exam answer - most likely an essay about Willy Loman - with some kind of irrefutable legitimising phrase along the lines of ‘as a songwriter once wrote.’ It wasn’t commented on - why would it be? - and I’m sure it didn’t advance the argument. I was doing this for no other reason than to make an arrogant teenager’s point: I like this stuff, and I’ve decided it matters, so you ought to know about it too.

A studio version of ‘From TG&Y,’ recorded at Electrical Audio, was uploaded by John himself, after he decided it felt ‘more in line with the Sunset Tree’ than the album they were working on at the time, which would become 2008’s Heretic Pride. Peter plays bass: this must be one of the last recordings they made as a two-person unit before drummer Jon Wurster joined the band. The track came with an authorial disclaimer: ‘I understand that by accepting this file, I agree not to be El Gran Senor Internet Douchebag, saying on various forums or lj comments threads how this song ought to have been on the next album instead of whatever other song I have blindfoldedly singled out.’ I don’t think I did this - I wouldn’t put it past myself - but it seems far more likely than the version I had in my head while contemplating Death of a Salesman was the live version I loved, as performed on 2nd December 2006, when Darnielle returned to Pitzer and brought Rachel Ware out to play and sing with him.

Before listening back, I’d imagined that this was one of the clutch of songs the two had performed together. It isn’t, but it’s easy to see how the subject matter melded in my mind with the dynamics of a reunion performance at Darnielle’s alma mater. Addressing this hometown audience as a 39-year-old professional musician, whose star had risen substantially a year earlier with a record recounting and framing experiences which took place a few minutes’ drive from here, the singer commented: ‘I wish you all could know what it’s like to come to back to Pitzer ten years later - it’s totally weird.’

As the set progressed, there were other moments of local recognition: look at the delirious grin that briefly crosses Darnielle’s face in the above YouTube clip when someone in the audience whoops at the mere mention of Mills Avenue. The version of Darnielle narrating that song was sustained by the vision of ‘good things ahead.’ This flash of joy, in a very different California dusk, is surely one of them. And then there’s the audible thrill when a listener recognises John’s reference to a ‘mysterious’ly-named drugstore where he’d go to shoplift magazines and cigarettes, and occasionally huff paint in the nearby alley. The store was part of a distinctly unloved retail complex called Peppertree Square, near a restaurant called the Green Burrito, at the intersection of Arrow & Indian Hill. ‘TG & Y,’ somebody shouts from the crowd, just before Darnielle gets to it, and he yells back ‘Damn straight,’ before introducing a song set right there.

This isn’t the kind of place songs usually take place: a run-down suburban thoroughfare along which a young man ‘stumble[s]’, leaving behind him a puddle of puke and blood. In response to the first verse you can hear quite a few people laughing: they might be motivated by this incongruity, or by the thrill of familiarity (‘I know that Safeway!’). At Pitzer, John took a course on the history of laughter with Barry Sanders, who had done stand-up as a younger man with Lenny Bruce. Barry emphasised to his students the thrilling, controlled exposure of improvisation before an audience - the tantalising vulnerability of its closeness to ‘bare naked truth’ - and introduced Plato’s concept of the ‘baited hook.’ ‘If I want to get a point across to Richard that may be painful to him,’ as Barry explained it to me, ‘the best way I can do that is with the spirit of comedy. And he will laugh at it, until he realises I’ve said something serious to him. But he’s already ingested it; he’s already taken it in.’

Something like that is what I hear in the laughter here - a way of gently inducting the listener into a depressingly grim scene before they realise what exactly is happening. The hopeless figure in the second verse, with no idea ‘what [he’ll] do’ if he isn’t able to ‘run away tonight,’ defines himself with images of shame over plaintive suspended chords: a ‘sick taste in [his] mouth’ and his proverbial ‘tail between [his] legs.’ But by this point, the crowd is fully drawn in: nobody is laughing any more. As in many of the darker Mountain Goats songs, the singer’s eyes are on the future, on survival, on getting beyond this whatever it takes: ‘Do what you have to do / Go where you have to go / When the time comes to loosen up your grip: you’ll know.’ And by the song’s end, when the singer has hoarded up enough of his ‘small resentments’ to have something to hang onto as a person, a collection of ‘rare and priceless gems’ that must be protected at all costs, Darnielle has moved into a register that’s soaring, corrosive, and clear as a bell, and it’s like that originating shame has been faced down and - in the words of another non-album track a decade later - ‘torched inside the fires of my transcendence.’

The first few times I heard this performance, it gripped me so viscerally that tears ran down my cheeks and left me shaking. This was a little surprising, because I hadn’t cried much since primary school: the paradigms of masculinity which I grew up with had framed this response as itself somewhat shameful. ‘A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us,’ an author once wrote, and here was a song that was doing something similar, splitting open a part of myself I hadn’t even realised had turned to pack ice. If I tell you that that quote comes from a letter to a friend by Franz Kafka, surely never intended to publication, you’ll understand that there’s a few things I’m still thinking through here.

In any case, it’s clear to me now how the Mountain Goats and the community I was discovering around them were starting to steer me towards other ways of being in the world. Listening back to the Pitzer performance, I’m struck in particular by the way Darnielle talks about ‘Garden Song,’ the predilections of young male singer-songwriters towards intense, stalker-esque narrators, and the absolute rejection he offers as an adult of the worldview songs like this might be taken to represent. The fandom around his music also tended to take ethical questions (like those around a stolen album, for instance) seriously, and its members tended to uphold - and have, over time, more and more explicitly championed - a set of leftist and feminist values. Did I take any of it in at the time, becoming a more evolved human being? Of course not.

At the start of the year, I’d spent a week with my fellow poetry prize winners at a residential writing centre in the Shropshire countryside: it was a giddy welter of private jokes and bonding over a shared, niche passion. The one-on-one tutorials and workshops gave me confidence in what I’d been doing so far, but the tutors’ feedback indicated that I still had a long way to go as a writer. Meanwhile, I’d started dating one of my coursemates, and gone to stay for a week at her parents’ house the following month.

This was my first real relationship - the first time I’d spent anything like this much time alone in close proximity to another person, having to be myself continuously in company - and I was not a good boyfriend. I was pompous, petty, clumsy and critical. It was uncomfortable when things ended for a number of reasons, not least that we were supposed to be on the editorial team of a new poetry e-zine together. All of us had a shared forum we’d been using to keep in touch and share work, named after - what else - a Libertines rarity. While our mothers had a couple of uncomfortable phone conversations about reselling the music festival tickets we’d no longer be needing, she posted a couple of new poems which were pretty unambiguous about the whole episode, and we all gamely commented on their form and phrasing, which is pretty much what I deserved.

A therapist, years later, told me ‘you can’t know what you don't know,’ meaning that some mistakes you have to make before you understand what's wrong about them. All of which might be true enough, but it's also true that we make those kinds of mistakes at the emotional expense of others - they're their learning experiences as well. At this point, having found a community and come pretty close to losing it, I was just glad the rest of the poets let me carry on being friends with them.

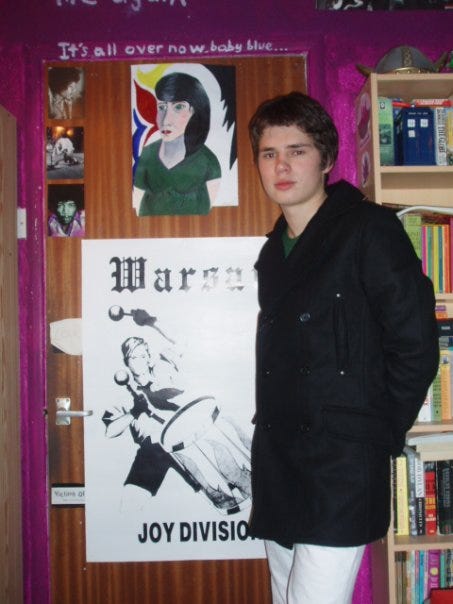

2007 was the year I first got on Facebook, and so unusually I have more than a very small number of photos to choose from for the episode’s representative picture. I did think about going for one from the course, to show we were all having a nice time together, honest - even if showing you pictures of us all at that age might be a little unfair to several future broadsheet journalists. Alternatively, I could show you me going to prom with a terrible haircut; in a sky-blue shirt and braces, dressed for a party as the Doctor Who character Captain Jack Harkness; or with a fake beard, in a Hawaiian shirt, playing Doc in our school’s modern update of West Side Story.

It probably makes most sense, though, to use the picture I had next to my author bio when I managed to secure an email interview with John Darnielle for the music website 3:am. I’m wearing white skinny jeans and a buttoned-up black peacoat, standing in front of my bedroom door. My hair is a little shorter than it had been for a few years. At some point I’d ended up having to cut it quite drastically because I’d fucked up the texture with a chemical relaxant made by a company called ‘Dark and Lovely,’ and then dyed it pink for a fancy dress party without bleaching it first, reasoning that leaving the dye on for twice as long as recommended would work just as well. It didn’t. The walls behind me are painted a head-shop purple, there’s a Bob Dylan lyric stencilled over the lintel, and the door is covered with postcards of Hendrix and Joe Strummer, a poster of Joy Division, and a sticker for local festival band Victims of Noise. I might have taken the picture on my camera’s self-timer setting - in any case, it’s an image I controlled and curated, unashamedly frothing with signifiers.

None of the questions I put to my new favourite artist were truly mind-numbing - like the time I asked a band with two singers why they’d decided on a ‘boy-girl dynamic with the vocals,’ and they responded ‘The decision was made when — during our first rehearsal — we happened to look down.’ But most of them reveal the questioner as supremely gauche, a teenage fanboy who just really, really wants to know what another person’s deal is: biography stuff, but also how this writer understands his own writing, what he’s reading, what his work is in dialogue with. I was asking, essentially, for suggestions for further reading, and John’s responses were naturally more interesting than what I was into at the time, based on my searching inquiries about On The Road and the Great American Novel. At one point, in the middle, I asked John how old he was. I might as well have asked him his favourite colour, or his favourite flavour of ice cream.

By 2015, Tom Breihan wrote ‘young men in dark rooms [had] been approaching Darnielle for a couple of decades,’ and in December 2007, I became one of them, while John stayed onstage to pack his guitar into his case after a short set at London’s Union Chapel, with Peter on bass, in support of Micah P. Hinson. I went to the show with my friend Catherine, a couple of years younger and one of the only people at school who I’d succeeded in getting similarly Goat-pilled. Looking back at the setlist today, I’m surprised to see a few titles I love which were never exactly big hitters - ‘Cobscook Bay,’ ‘Tulsa Imperative’ - and that the band closed with a cover of Nothing Painted Blue’s rather twisted ‘Houseguest,’ but didn’t play ‘No Children.’ I’d also completely forgotten that Eddie Argos from Art Brut joined the band for back-up vocals on ‘The Best Ever Death Metal Band in Denton,’ a transatlantic indie crossover event documented only in a single blurry clip on YouTube. But I don’t remember there being any songs I didn’t know: thank the forums for that.

One of the only extant recordings from the night, on YouTube, documents the sense of a gathered community, excited to share and participate in this music, which I was steadily becoming a part of. ‘There’s only one place this road ever ends up,’ Darnielle sings in the second verse of ‘Dance Music,’ before imploring the crowd: ‘Sing it!’ A chorus of voices, mine indistinguishable but present among them, responds with a unified affirmation: ‘I don’t wanna die alone.’ The phrase might have started with the singer up on stage but in this moment of transference, it belongs to all of us, and in that moment, we’re none of us as alone as we used to be.

This week Richard is getting into Inspector Maigret.

Huge thanks to Liz Hamilton for tracking down the source of this live banter quote!

Share this post