John Darnielle can be a hard guy to keep up with. It’s not by chance that two of the first six entries in this series have been about songs with ‘Going To…’ in the title. Even from a small room in Norwalk, Darnielle’s thoughts have consistently been pointed outwards: in 1995 alone, he sang in the voices of characters in Utrecht, Tahiti, and downtown Seoul, with correspondents reaching out to them from the Hunan province and from ‘all the way across the country in Palm Springs.’ Only a few months earlier, he and bassist Rachel Ware had played their first batch of East Coast shows, discovering in the process some inspiring infrastructure. Driving from Massachusetts to Long Island, Darnielle said,

I saw a sign, and it said ‘Throgs Neck Bridge.’ And I thought, you know, I’m from California, our bridge would be called, you know, Something Spanish Bridge. And so I was like ‘Throgs?! These people are from a different universe! Awesome, I gotta use that!’

Setting aside the universe-expanding possibilities of Throgs, Darnielle hadn’t been to the majority of the places mentioned in these songs at the time of writing. Nonetheless, his enthusiasm for local detail brings us most of the way with him on these imaginative journeys. In ‘Going to Port Washington,’ Darnielle might actually have seen how the trees of New York looked, ‘all decked out in their best fall colors’; how its particular local sunlight might bring out the highlights in a lover’s hair. But as listeners, in just the same way, it feels as if our own eyes are opening for the first time on the ‘tropical hardwood’s of Bolivia, populated with leaping monkeys and ‘wildcats I had never seen’; or ‘the red brick building / By a bright green field’ in Denmark, a ‘very old country’ of the kind the singer was starting to visit in his first European tour in April of 1995.

Having long abandoned the idea of becoming a professional musician, suddenly his songwriting was opening up new spaces to him, and not only geographical ones. After the breakup of a four-year relationship in which he’d been going to Mass every Sunday, John was feeling himself to be ‘on [his] way out of the Catholic Church.’ At Los Angeles airport on his way to the European dates – the first time he had ever flown internationally – he accepted a copy of The Science of Self-Realization from Aishwarya Das, a member of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. By the end of the same year – if I have my timings right – for their first Christmas together, John’s new girlfriend Lalitree had given him a book of maps as a present.

But of course, Darnielle’s interest in place and its meanings long predates a knowing gift from his future wife, or the mixed blessings of an expanded touring schedule. In the grim hour when I briefly considered pitching this project to an academic publisher, I imagined that its title would end being something like John Darnielle and the Romance of Place. That version would presumably have had to start with this anecdote:

I think it’s because when I became conscious of being a person, when I was very small, I knew that I was from Indiana, but I had never seen Indiana. I was born there [in Bloomington], but we moved when I was, like, a year old. I always had a sense of a place that was far away from where I was…1 My family, before the divorce, moved several times, and after that we moved a whole bunch more times, and so I don’t have an anchor to a single place. Probably as a result of that, I’m a little more attenuated to when people do feel close identification to place, whether they say it out aloud or not.

As someone who grew up in the same house, in the same small village, from birth to the age of eighteen, my sense of place was somewhat narrower. For most of my time living in West Deeping, it didn’t even have a shop (in my late teens, someone opened a short-lived artisan glassblower’s). My old English teacher, Carol Atherton, had a quote pinned on her classroom wall from Graham Swift’s novel Waterland, set in the region, which has always stuck with me: ‘To live in the Fens is to receive strong doses of reality. The great, flat monotony of reality; the great empty space of reality. How do you surmount reality, children? How do you acquire, in a flat country, the tonic of elevated feelings?’2

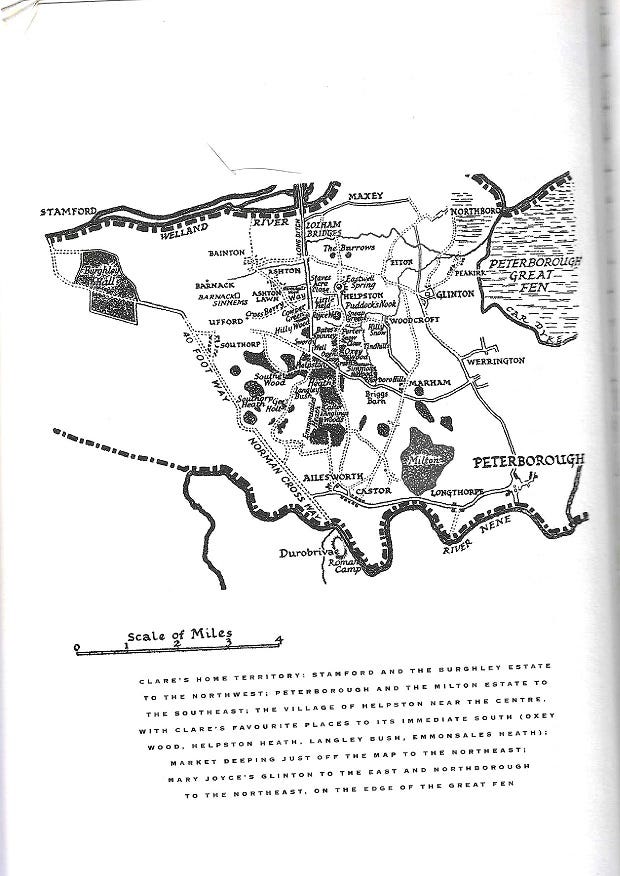

In a blog post this year, Dr Atherton expanded further on Swift’s description: the Fens are ‘a weird landscape, huge skies, flatness, and the constant presence of water, pumped out from the land into drains and ditches, gleaming straight lines of silver. No broad sunlit uplands; no moments of the sublime.’ I didn’t, for all this, totally share local poet John Clare’s conviction ‘that the world’s end was at the edge of the horizon and that a day’s journey was able to find it’3 – perhaps at least in part because of my dad’s relationship to Ireland, where he spent the first five years of his own life being looked after by his maternal grandmother and which he’d always had a none-too-subtle habit of describing wistfully as his one true home.

I was from here, but my parents were car commuters, two in a growing wave of urban transplants. And though our elderly neighbours had spent their whole lives in the area, far fewer people than in Clare’s day now made their living from working the land. On a webpage for its 14th-century church, West Deeping is characterised as ‘a village of around 120 houses and a population of approximately 270 spanning all age groups,’ but this latter phrase comes as news to me. The village school had shuttered in the 1970s. Instead I started at St. Augustine’s R.C. Primary School in the Georgian town of Stamford, six miles away. At some point in my first year there, my family visited an exhibit about the Canterbury Tales - still resolutely far from the top of the bestseller list - and I had this photo taken of myself in the stocks.

Determining dates for this image, in a text exchange with my mum, was more complicated than expected – apparently there is least one other picture of me standing in the stocks as a child. I also brought back a leaflet about my school’s namesake, the 5th-century bishop of Hippo and author of the Confessions, to show my headmaster. This does now seem like the sort of thing you’d be more likely to do if, growing up, there were hardly any children your own age in your immediate environment. As my wife commented last week when she visited the place where I grew up for the first time, after a couple of days exploring the local streams and fields and sitting out in my mum’s lovingly-tended garden at night to watch the bats fly overhead: ‘No wonder you know so much. There’s nothing to do here except read.’

John Darnielle’s childhood was very unlike mine, but his wide-ranging curiosity, or what Grayson Haver Currin calls his ‘aggressively absorptive mind,’ clearly set in early. As a boy, he used to call Indiana ‘on Christmas morning … to find out what the weather was like.’ At some point between this and starting an undergrad degree in English and Classics at Pitzer College, Darnielle notes that he ‘read too much Arthur Conan Doyle… and got this idea that a gentleman should know a lot about one thing and plenty about most everything else.’ The studies he was finishing up in in 1995 must have further deepened these tendencies. Things could have gone further, as he told Bandcamp in explaining the source of the song title ‘Exegetic Chains’:

In many ways, what I am is a failed academic, right? My goal coming out of college was to get into grad school and teach Latin or English. Well, I didn’t get into grad school, so my consolation prize is that I became The Mountain Goats. You could do worse, right? I don’t have any complaints. But at the same time, when I read this stuff, I remember how bad I want to actually know the stuff that the people who have doctorates know.

Whatever happened around the end of John’s B.A. was the opposite of the fortuitous fortune of ‘Going to Port Washington,’ the constellations gently aligning. As he explained to Joseph Fink, one of his letters of reference was never submitted - the teacher who was supposed to write it had fallen terminally ill and presumably, understandably, wasn’t on top of her correspondence. So Darnielle’s formal academic career, to date, culminated in a translation of Silver Age Latin playwright Seneca’s tragedy Thyestes, whose closing dialogue Darnielle describes as ‘so brutal, even after centuries of horror it’s shocking,’ submitted for his senior thesis.

Around the same time, John formed an ephemeral band with Lalitree called the Seneca Twins and wrote a Greek tragedy final on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. In an interview with a Kansas college radio station, he mentions a second thesis in English, with both projects exploring how readers juggle the fact ‘we all need narrative’ with the ‘terrifying’ prospect that ‘if you want to be honest, none of it makes sense … and if none of it makes sense, then you don’t have any moral or ethical obligations.’ Speaking of his own work, he connects its approach to that of classical tragedy, which is ‘trying to impose connections where there are none; trying to state cause and effect where cause and effect do not exist’; any individual piece of writing is therefore ‘the attempt to put order on chaos,’ with narrative as a way of explaining to ourselves some of the world’s violences so that it doesn’t all feel so pointless that we’re tempted to reproduce them.

What I’m doing here is also some kind of attempt at imposing order – my own book of maps, my way of trying to ‘put straight lines on things.’ This post was supposed to be my engagement with the sorts of things John was reading in college – getting my head around some of the classical literary sources that, as one of the people who have doctorates, a lecturer with a PhD in Shakespeare Studies, I feel I should have read years ago. My Latin extends to canem est in mensa – my secondary school’s last teacher of the subject left the year I joined, and I picked up a couple of basic phrases from a lunchtime club run by his former students, who I now realise were some extraordinarily dedicated seventeen-year-olds.

I’ve got plenty of friends with deep knowledge of the subject, and on a break from writing this episode I even helped my wife answer a trivia question on a phone app about Doric columns. But as with so many things from my undergrad education, for a long time Classics felt to me like something which lived behind an impenetrable wall of class – that if you hadn’t picked it up in private schools and summer camps, you’d never be on a level playing field with the people to whom it was second nature. It’s my loss, but I didn’t know that then.

All of this to say, while little mortifies me more than not having done the reading, I should probably have realised I wasn’t likely to be able to give myself a full classical education in a fortnight. But then I’m not sure Robert Fagles’s translation of Antigone gave me a clearer understanding of ‘The Recognition Scene’ than John’s live comments, which indicate what the concept is about for him: a ‘true story’ about ‘a moment in every relationship where you look at the person you love and you think inside yourself: “Well, I don’t actually love you anymore. What am I gonna do now?”

The simultaneous knowledge that this is ‘the only love I’ve ever known’ and that ‘I’m gonna miss you when you’re gone’ is not an emotional state unique to Greek tragedy. This does, however, usefully illustrate something Franklin Bruno said to John in a ‘Shrimper-licious mutual interview’4 for a zine linked with their shared record label in 1994: ‘more consciously than a lot of songwriters, your imagery comes from, one might call it for lack of a better word, “traditional” themes.’ John agrees, or at least asserts that ‘I don’t read modern literature, so most of the stuff that influences me is stuff that’s so dated at this point, and so largely unread that it seems novel … once you get over the urge to try and say something absolutely new, then you realize you have a vast rich body of images to work with.’

A more recent interview sees him reflecting on the ‘miracle’ of memory and the potential for ‘terrifyingly direct communication’ between performer and audience in oral tradition: ‘I think a lot about how by the time people start writing down the songs that they know, especially in English, they’ve been singing those songs for a very long time.’ As pirates burn the boats of a corrupt Roman governor’s love rival at the end of ‘Song for Cleomenes,’ Darnielle inhabits the voice of a community who gather in the Sicilian harbour to hear what were already ‘the old songs’ by the time of Cicero.

The whole thing reminds me of ‘The Ruin,’ an Old English fragment I studied on a course on medieval poetry, in which a poet writing maybe two centuries before 1066 brought the Norman Invasion describes life in the shadow of a Roman wall, ‘lichen-grey and stained with red,’ which has already ‘experienced one reign after another’ and whose ‘mighty builders’ now lie in ‘the hard grasp of earth.’ A hundred generations later, ‘this red-curved roof / parts from its tiles / of the ceiling-vault,’ but the speaker can still imagine the days when ‘the wall enclosed all / in its bright bosom, where the baths were, / hot in the heart.’ The last few lines following this are riddled with lacunae, the poem seemingly crumbling to dust before the reader’s eyes. When I tried to track down the provenance of the translation I’m citing, by Jack Watson, the link provided was no longer operable. ‘The Anglo-Saxon Poetry Project’ led to a spam post marketing the Kindle eBook reader.

Something about this reminds me of John adlibbing some of his favourite lines of poetry, largely off the mic, at the end of live performances of ‘Tollund Man’ – a song inspired by a college archaeology textbook. The resigned ‘goodbye, goodbye, goodbye’ of the final sung line in this eight-line song turns out not to be the end at all: over furious strumming, we might just about be able to make out that the scene has shifted from the ‘cooked wild grasses’ and ‘ceremonial shoes’ of prehistoric Denmark to the rain moving ‘like silken strings’ down a Bournemouth window in the 19th century, in a poem by Thomas Hardy, or to other worlds conjured up by Shakespeare, or John Berryman, whose work the young Darnielle transcribed into notebooks ‘to see how it felt to write down lines like these.’ He told something similar to the young O’Brien, when I interviewed him in 2007, and asked him, of course, about his literary influences: ‘Berryman is the big one, that merging of high and low diction, and of personal and broader themes: for twenty years I’ve been trying to hit the vein he hits.’5

Other favourite authors cited in his discussion with Franklin Bruno thirteen years earlier included Chaucer, Horace, Petronius, Catullus, Juvenal, Faulkner and Yeats. This might seem to make his influences a distillation of the white, male Western canon, and to an extent those guys are in there. But the first Mountain Goats tape, Taboo VI: The Homecoming, recorded before the start of John’s BA, already makes reference to Mahayana Buddhism, and by 1996 its author had become a practising Hare Krishna, making regular offerings to household deities – the only person wearing a bead-bag to the post office in Colo, Iowa. Lyrics in these college years also draw on Nahuatl poetry and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.6 In whatever context, something that seems to engage Darnielle when he’s reading, is the spark of recognition:

the closing stanza [of Berryman’s ‘Tampa Stomp’] begins with a line whose resignation, whose need to reconcile righteous anger with mercy, is familiar to anyone who “has suffered an irreversible loss,” i.e., to all of us: “Ah, an antiquity, a chatter of ghosts.”

‘The Recognition Scene,’ the opening song on Sweden, refers to a different kind of recognition, and one less likely to provide much immediate comfort: the title is a translation of anagnoresis, a term which Aristotle defined as ‘a change from ignorance to knowledge, and thus to either love or hate, on the part of the personages marked for good or evil fortune.’ What I imagine appealed to Darnielle about the phrase was that sense of sudden escalation, of the bottom dropping out of a moment under the weight of some force more powerful than human agency, our normal relation to the shape of things breaking off like a dodgy doorknob. This is what connects two young lovers, opportunistic thieves beside themselves at the luck of finding three months’ worth of candy unguarded, with the extremities of the Greek tragic stage: the shared experience of everybody who ‘thinks they’ve been acting independently and just deciding what they were gonna do’ realizing that ‘they’re totally fucked.’

Thinking about John’s college curriculum, these ideas resonate both with Antigone (the text he’s describing onstage there) and with Things Fall Apart. The differences between them, needless to say, are many and various – I’m not a comparative literature specialist. But both texts might have spoken with an echoing intensity to a reader with his own developing interests in communicating heightened states of feeling. Both depict worlds of agonising intergenerational conflict, watched over by potentially vengeful ancestors, chiding oracles, and gods capable of ‘terrible flowering rage.’7 Both feature striking escalations of violence, banishment from a community governed by strict laws and ritual, and the troubling presence of a body left above ground without due burial.

I’ll remind you of the Old Man in the Sourdoire Valley – the first known hominin to be carefully placed in the earth – and of the old blood soaked into the soil of California, seeping up into the blossoms of the jacaranda. These are the kind of things that don’t appear on any map. Darnielle glosses the Berryman line above as a reference to ‘inescapable formative years. The things that made us who we are, as distant as ancient Rome and the people who lived there’; a distance which optimistically suggests the past ‘can’t really hurt us any more, unless, of course, as it often turns out, it does.’

This week, Richard is getting into mortgage paperwork.

In the podcast interview quoted above, with Shivam Bhatt, John refers to it as ‘a mythical country.’

Graham Swift, Waterland. Revised edition, Picador, 1992.

Jonathan Bate, John Clare: A Biography. Picador, 2003, p.41.

Thanks once more to Christopher MacMurray for digitising these pages.

Rest assured, a future post will engage at length with the question of what the 17-year-old me thought I was doing in some parts of this interview.

Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart (1958). Penguin Classics, 2001.

Sophocles, Antigone. The Theban Plays. Translated by Robert Fagles, with introductions and notes by Bernard Knox. Penguin, 1984, p. 108.

Share this post