All right, I’m on King Street, in West Deeping, Lincolnshire, and I’m fifteen years old, or sixteen maybe. I’m dicking around on the Internet, looking for music on a peer-to-peer file-sharing service. It could be Limewire, or Kazaa – all I remember is the colour green, and that I’ve been using this kind of software long enough that doing so would be unremarkable. The connection, at least, is probably better than it was a couple of years earlier, when I got into a humiliating and ridiculous yelling match with my Dad for inadvertently booting me off our screaming.net dial-up service to check his emails – or even possibly to make a phone call – while I was halfway through a three-hour download of Definitely Maybe by Oasis.

I’m in the ‘band-names-and-lyrics-scrawled-on-a-year-planner’ phase of teenage music fandom, expanding my taste in all directions. Part of my collection comes from pocket-money purchases at Virgin, HMV (The Clash, Vendetta Red) and a comically unfriendly indie store named Pendulum Records in the Georgian town of Stamford, where they’d recently been filming the Joe Wright film of Pride and Prejudice (Rock Against Bush). Much of it, however, is gathered on the digital high seas, by which I mean through open piracy. And it’s on one of these low-stakes raiding expeditions that I take a small detour, out of idle curiosity, of a kind that I have a strong (and possibly unjustified) feeling was more available to a teenager in the early days of Web 2.0 than ever before or since. I’m torrenting something from another user, and I guess they’re not particularly concerned with privacy, because the system lets me click around the music folders on their hard drive and see what else they’ve got in there. ‘The Mountain Goats,’ I think: that’s a cool name.

On no pretext that I’m aware of beyond that, I grab the three most recent albums: Tallahassee, We Shall All Be Healed, and The Sunset Tree. It’s open season in the pre-streaming days of finding music online, so I’m sure I pick up a few other things as well. I can’t tell you if I listen to them immediately, or in what order, but I’ve got a good sense of the first two songs that really register – ‘Southwood Plantation Road’ and ‘Dance Music’ – and after that, a steady feeling of my interest in the artist growing. What I want to emphasise, given the importance that this music has gone on to assume in my life, is how haphazard, how provisional the discovery was – like an archaeologist stumbling across a hidden door, applying a slight pressure with his shoulder, and falling into riches and wonders.

Piracy is a complex subject, and not one on which John Darnielle has made a single, definitive statement (unless you count ‘High Barbary.’) Like many independent musicians with a significant online presence, he recognises the role it’s played in introducing his songs to a global audience of previously unimaginable scale: ‘anything that involves people discovering and being interested in my music, I’m in favor of … I can’t [take it personally],’ he commented in what reads as an uncomfortably combative interview with MTV’s Eric Spitznagel. It’s also, evidently, one of many factors which have made it difficult for artists over the past twenty years to make a living from their recorded work.

I’ve spent a good deal of money on the Mountain Goats since 2005, but my first engagement with their music came through a pretty unambiguous act of theft. Like many of my experiences as a member of the first generation to really come of age online, this act involved ethical considerations I probably wasn’t ready to make, within a framework which the adults around me probably understood even less than I did. But it happened, all the same, and it changed me. Helena Fitzgerald has observed that John Darnielle’s writing, whether overtly autobiographical or cryptically coded, feels personal, to her as to myself and to countless other fans, ‘because I have made it personal to myself… [t]he vulnerability we take away from it is our own.’ As she says of her own relationship with the Mountain Goats, ‘Love anything long enough, and it becomes a form of record-keeping.’ For me, then, this moment is where that process of discovery started. This is where the records began.

The Sunset Tree is itself pretty invested in records: the kind you listen to, but also how the presence of that kind intersects with how you remember everything else. Darnielle has written and spoken at length elsewhere about the music he was listening to during the particularly intense summer of 1984 which much of this autobiographical album addresses: Sisters of Mercy, the Birthday Party, Leonard Cohen and the Stockholm Monsters. These artists provided the soundtrack to a time of ‘near-total isolation’ in his girlfriend’s bedroom, with whom Darnielle was getting into hard drugs; the alternative was spending time in the house he shared with his mother and abusive stepfather, where he contemplated suicide ‘every single day.’ None of them, however, is directly mentioned in the lyrics of the album, and even its most famous mention of music – ‘Lean in close to my little record player on the floor / So this is what the volume knob’s for’ – is partially occluded: the real-life inspiration for this image in ‘Dance Music’ was a flexi-disc player the young Darnielle had received for Christmas with a recording of the moon landing to which he would listen ‘in times of distress.’

While Darnielle seems to revel in the hermetic significance a musical reference can hold elsewhere on The Sunset Tree (‘Dinu Lipatti’s Bones’), these lines in ‘Dance Music’ are emphatically open. If the markers of time and place (San Luis Obispo, the Watergate hearings) ground the song firmly in the singer’s personal experience, the hook offers the listener a kind of invitation to supply the soundtrack of their choice. In the song I’m focusing on as a window into this album, ‘Hast Thou Considered the Tetrapod?’, unnamed music functions similarly. At first, ‘I’m in my room with the headphones on’ might read as a primal scene of teenagehood (he could be listening to anything up there, though as Darnielle places the memory at age 13, it’s plausibly Bowie or Lou Reed); seen closer, it’s a cutaway into the only part of an unliveably brutal household that still seems to make sense. Whatever’s playing on those headphones is at once a way of painting a specific moment – a memory that occurred to a sleepless Darnielle on tour in London which he ‘hadn’t thought of in a long time, and it was kind of a germ moment for the rest of the album’: ‘Remember that time you came home and woke up your stepfather?’ – and a sort of portal evoking everything beyond that time and that house for the young narrator who can’t yet escape it.

In classic Mountain Goats style, the song has only two verses and two chorus-type sections – there’s no repeated refrain and something distinctly different happens at the end of the second. The first verse sets the scene, establishing everything that’s important about the place (‘it’s a hot Southern California day’) and the people: ‘You are sleeping off your demons’; ‘I am young and I am good.’ Darnielle’s stepfather, who is also depicted sleeping on the previous song ‘Lion’s Teeth,’ is again sketched in a position of vulnerability, one made possible by their domestic intimacy. ‘Children love their parents even when they have awful parents,’ Linda Wertheimer observed to Darnielle in a 2005 NPR interview, and he responded: ‘Of course you do. I love my stepfather, you know … my stepfather loved his family, right? Now he mistreated us terribly quite often, but he loved us.’

Living together day after day, Darnielle saw many sides of Mike Noonan, publicly known as a trade unionist and community activist. Calling his violence at home ‘the most important fact about him,’ Darnielle still mentions his investment in teaching his step-son ‘progressive values.’ That inner conflict informs later songs like ‘Love Love Love’ and ‘Pale Green Things’: here, the focus is sharply maintained on the ongoing struggle between what the previous track called ‘great big you, and little old me.’ The singer is standing close enough to see ‘spittle bubbling’ on the lips of a parental figure who will later hurt him. The verse concludes, like the album’s best-known cut ‘This Year,’ with a certain intimation of violence on the horizon – ‘If I wake you up/There will be hell to pay.’

All of this is over simple open chords played with a capo on the first fret, slow, plangent and ringing. The progression and the pacing have an entrancing quality which is deepened by Peter Hughes’s measured bassline and a booming drum, so quiet you sometimes forget it’s there, like a large presence moving through the depths of the water. These elements together plunge us into the space of meditative separateness the song only gives us a name for once we’re sure it’s about to be disrupted – ‘the dream chamber’ of listening to music on headphones, where you can explore possibilities of being in the world outside your own life:

And alone in my room

I am the last of a lost civilization

And I vanish into the dark

And rise above my station

Rise above my station

The song’s gradual movement, and the inevitability of what’s coming (by this point on the album, at least three outbreaks of physical violence have been directly mentioned) don’t diminish the sinewy power of Darnielle’s delivery when he describes what happens next: ‘But I do wake you up, and when I do / You blaze down the hall and you scream.’ The dream chamber, a state of reverie, is described in two lines before being abruptly whisked away. ‘The delicate balance’ in the house ‘has shifted,’ as Darnielle feverishly reports in ‘Dilaudid,’ and sleep or peace are no longer on the cards for anyone: ‘And then I’m awake and I’m guarding my face / Hoping you don’t break my stereo.’ That totemic object, ‘the one thing I couldn’t live without,’ is held mentally aloft – ‘I think about that’ making it the last thing above the surface before the speaker ‘sort of black[s] out,’ before the oceanic quality of the song coalesces in the image of the singer’s stepfather’s ‘strong and thick-veined hand’ holding him metaphorically ‘under these smothering waves.’ This, in turn, brings us to the final image introduced in the title, whose pseudo-Biblical register points much further back to the origins of terrestrial vertebrate evolution: ‘one of these days / I’m gonna wriggle up on dry land.’

Talking to SPIN magazine’s Joe Gross about his teenage experiences, Darnielle described the frustration of other people telling him that ‘this will pass’ someday: ‘“Someday you won’t be hungry,” is not something you tell a hungry person. You have to break it down so that you’re telling yourself, “It gets better by the end of the day. It gets better in half an hour.”’ But in the space of the song, ‘one of these days’ has a different valence – rather than breaking the time of endurance down into its smallest components, instead ‘Tetrapod’ expands it to the scale of geological epochs. Hast thou considered, the song asks of its characters, that someday things will have to change, that they can’t go on like this forever? The tetrapod is evidence enough, representing not patience so much as a promise to the self: no matter how long animal life had been living in the planet’s seas, one day, one creature was able to make a decisive movement; life, in the sense of a will to survival, has dragged itself out of the depths before.

The vocal melody on the album recording, as this statement is propelled by the highest and tensest chord in the key, has a slight rippling (or wriggling) quality, but in live performances Darnielle tends to reach one note and grab it for the duration of the phrase, to ‘hold on for dear life’ to every single syllable: ‘I’m gonna WRIGGLE UP ON DRY LAAAAAND.’ It’s like that final lyric becomes a life-raft, and one that has somehow been there a long time: a spirit present in the ancient oceans is still present at the core of its distant descendant, a vulner able child in a California bedroom, and thinking about how far back this impulse to survive must go offers a mantra to repeat in an unliveable present. What seems at first like dissociation reveals itself as an encounter with deep time.

Not for nothing, I think, did Darnielle tell a 2004 Washington Post interviewer that ‘I play the kind of punk rock music that has existed since the time of the great painters in the caves at Lascaux.’ And that space, in which early humans made their homes and produced their first known artistic output, is one to which he’s repeatedly returned: in ‘Soudoire Valley Song,’ ‘Grendel’s Mother,’ and two separate references to Plato’s allegory of the cave in ‘Minnesota’ and ‘For the Portuguese Goth Metal Bands.’ Darnielle has even connected paleo-art directly to singing, which he called ‘the earliest of forms’ except ‘probably painting’ – the Costa Rican golden toad’s deep-seated impulse to ‘try my tiny song’ as a way of ‘claim[ing] my place beneath the sky’ in ‘Deuteronomy 2:10’ places the origins of music still further back. As he put it to Helen Rosner, ‘To me, we start singing as soon as we’re born. The song is everything. Every other form aspires to the natural condition of the song.’

Recorded at the beginning of the 2020 lockdowns, Dark in Here suggested a virtue in returning the form to where it came from: Darnielle’s press kit called the album a set of songs ‘for singing in caves, bunkers, foxholes, and secret spaces beneath the floorboards.’ The concept emerged even when Darnielle discussed with Joseph Fink another particularly primal feeling to which his writing often returns, a thematic present on The Sunset Tree in ‘Up The Wolves’ and ‘Lion’s Teeth’ and apparently foregrounded in the recently-announced Bleed Out: revenge. Opposing the desires of the ‘baser self’ to the ‘human element’ of social constraint, Darnielle notes that no matter how strongly his beliefs encourage the latter, the former dates back a pretty long way: ‘We’re actually, what are we – creatures from caves, right?’

Increasingly it seems to me that ideas like this underlie an impulse I find in many Mountain Goats songs: to dig down beneath the surface, to sift through the layers of biography and history, to find some human continuity underneath them – which may or may not be wholly positive.1 The ‘old blood’ that soaks the soil in ‘Going to Alaska’ re-emerges in ‘Minnesota,’ ‘coming up through the wooden floor again,’ and it’s hard not to read in the title of the band’s forthcoming 20th studio album a testament to this endurance. As I write this, I have a tab open on YouTube to consult live performances, and there’s a video (from PBS Eons) suggested to me in the sidebar with the title ‘Something Has Been Making This Mark For 500 Million Years.’ Blood isn’t the mark most of us would prefer to leave on the world, but there’s a perverse joy to its invocation in the liner notes already available online: ‘May your blood stain the concrete, the asphalt, the Miami streets, and the carpet of the banquet room in the upstairs of a Little Italy restaurant forever.’

In Darnielle’s latest publication, Devil House, the narrator describes a booth in an abandoned adult video store which a group of teens have decorated with ‘symmetrical waves flowing down each wall from ceiling to floor, dazzling to the eye, not painted but carved, like ancient symbols from cave walls in the deserts of the West’ (p. 213-4). The speaker calls our attention to ‘the subsuming totality of the Word’ which flows over ‘every surface’ of the redecorated space as a perversion of ‘the human function of language – to share, to bridge a distance’ (p. 212) – but in so doing, reaffirms the significance of that function, and the depth of its history. The following sections depicts an ‘ogre’s cave’ in the tradition of medieval romance, where its protagonist, Gorbonian, reads the ‘notches scored into’ a ‘free-standing stone’ before falling asleep. As in ‘Bell Swamp Connection,’ he undergoes some kind of ambiguous revelation in response to these mysterious and presumably ancient ‘markings,’ waking ‘as from the slumber of ages’ to find himself filled with ‘some spirit sounding music, its melodies strange but not newe fangled’ (p. 248).

Gorbonian’s narrative cuts off, in true Chaucerian style, before he is able to ‘make known’ to the reader the ‘things kept hidden’ and now bound up in ‘this song within’ (p. 248), but one of the novel’s broader interests is in how ideas carry forward even if unfulfilled, how every generation tries to restore its own temple in its own way. In this it reflects a concern Carl Wilson identified in The Sunset Tree, with ‘the larger cycles that make people and things the way they are, cycles indifferent to our judgments, sweeping all before them.’ What persists through these cycles is a desire to make art, to pursue self-expression, in the knowledge that any mark you leave might soon enough be effaced by that rolling tide, that the ‘tiny song’ you feel nonetheless compelled to sing will be carried away and fade into the air. Edmund Spenser, quoted in ‘Minnesota,’ writes elsewhere in his sonnet sequence Amoretti about the compulsion to create in the face of oblivion:

One day I wrote her name upon the strand,

But came the waves and washed it away:

Again I wrote it with a second hand,

But came the tide, and made my pains his prey.

A writer more local to me, the Venerable Bede, preserves a nameless seventh-century nobleman’s comments on the transience of all life. The words themselves have endured to this day, though their context (that given life’s brevity, it’s worth becoming Christian if it brings ‘any more certain knowledge’ of our predicament) is perhaps less well-known.2 Shortly after hearing ‘one of the king’s chief men’ make the following observations, the Chief Priest of a pagan religious site ‘far east of York, beyond the river Derwent… known today as Goodmanham’ set fire to his own temple, ‘full of joy at his knowledge of the worship of the true God,’ ‘desecrat[ing] and destroy[ing] the altars that he had himself dedicated’ in the white heat of conversion:

Your Majesty, when we compare the present life of man on earth with that time of which we have no knowledge, it seems to me like the swift flight of a single sparrow through the banqueting-hall where you are sitting at dinner of a winter’s day with your thanes and counsellors. In the midst there is a comforting fire to warm the hall; outside the storms of winter rain or snow are raging. This sparrow flies swiftly in through one door of the hall, and out through another. While he is inside, he is safe from the winter storms; but after a few moments of comfort, he vanishes from sight into the wintry world from which he came. Even so, man appears on earth for a little while; but of what went before this life or of what follows, we know nothing.

Though this passage hasn’t yet moved me to arson, I’ve been thinking about it a lot recently, since I stumbled across a piece of public art just off the Westgate Road in central Newcastle. Embedded in the paving slabs outside Hair Mechanics and The Party Shop is an embossed strip of stainless steel along which runs Tyne Line of Txt Flow: ‘a 140 metre-long introduction to northeast history written in the form of a collaged poem’ by W. N. Herbert, in collaboration with artists Carol Sommer and Sue Downing. Herbert incorporates the words of the sparrow passage, but renders them in a txtspeak-inflected English orthography which was cutting-edge for the year it was installed, a date I only discovered when trying to find out anything I could about the artwork online: 2005. For millennial Bede, who is here cited alongside Lindisfarne Gospels scribe ‘Billfrith, D anchorite,’ life is ‘Lk 2 D swift FlyT of a sparrow Thru D Hous wherein U sit @ supper n winter, W/yr ealdormen n thegns.’ Herbert’s updating, encountered seventeen years later, has an unusual effect which this noted poetic prankster may well have intended. The digital register of the mid-2000s becomes itself a relic of another ‘Tym wich S unknown 2 us’: a time of clunky Nokias and charity wristbands, MySpace meetups and Iraq War apologism, Veritas and the foxhunting ban, the return of Doctor Who and the demise of Littlewoods – ‘the things that made us who we are, as distant as ancient Rome.’

This is what Darnielle in Devil House calls ‘the proximity effect: the closer you get to the past, the less believable its particulars seem’ (p. 28). Nonetheless, the book attempts to take stock not only of those recent particulars, but of the deeper currents and accumulations towards which the Gorbonian section points us. Monster Adult X, where the murders pivotal to the novel take place, was once, in ‘a past no one remembered,’ ‘a place where people gathered, and ate, and slept, and lived’ (p. 162); then it became a luncheonette, a soda shop, a newsstand, and a porn store. The people squatting in it in 1986 construct, out of cardboard from repurposed adult VHS sleeves, a huge art project which the narrator addresses as ‘The Great Angel of the Transformation’ (p. 233). Overseeing, with a pained expression, this historically layered space, it has something of the quality of Walter Benjamin’s ‘angel of history,’ the theorist’s poetic gloss on a small Paul Klee painting of an angel with its face ‘turned toward the past’:

Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

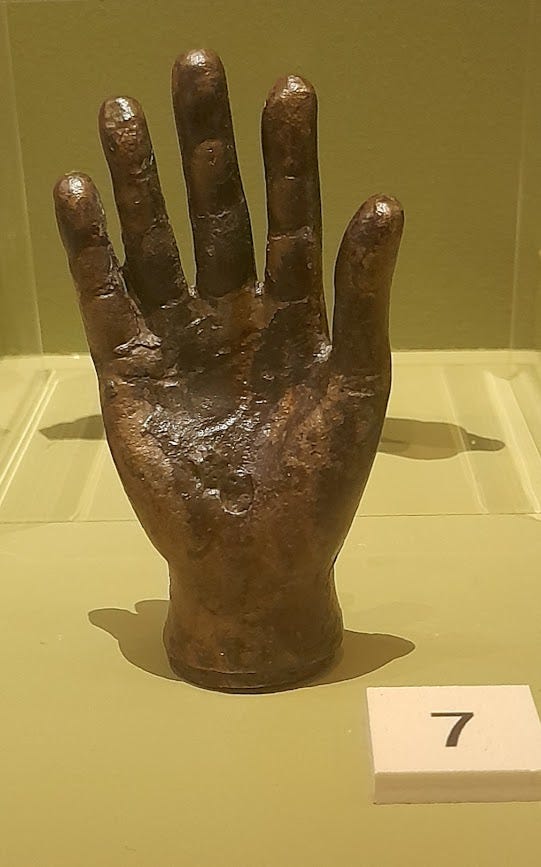

In ‘Tetrapod’ too, the possibility of ‘progress’ can’t be separated from the past’s inexorable pull, but the titular creature’s tenacity indicates a way forward. This is what Darnielle told No Depression he wanted The Sunset Tree to do, the thing that music itself had always done for him: ‘held my hand when I was walking down dark alleys and couldn’t see my way out.’ In a 2011 interview, he took this image of the hand still further, explaining that he wanted his work to sound so natural, automatic and direct, that it should feel ‘like at some point a hand is going to reach out from the speaker and touch you on the chest.’ Keats, two centuries earlier, wrote a fragment of a poem which makes a similar gesture, summoning up ‘both warm life and cold death […and] the understanding that the two are inextricable’:

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou wouldst wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calmed—see here it is—

I hold it towards you.

On ‘Harlem Roulette,’ Darnielle would later evoke the threatening ‘shadow-hands / Reaching out to sad young frightened men,’ while in one of his best-known songs, taking another person’s ‘unlovable hand’ is a surefire route to certain destruction. But the hand that The Sunset Tree offers its listeners is closer to the image of distant kinship described in a quote on the wall of my secondary school English classroom, from Alan Bennett’s The History Boys. Finding in literature ‘a thought, a feeling, a way of looking at things — which you had thought special and particular to you […] set down by someone else, a person you have never met, someone even who is long dead,’ the speaker observes, ‘it is as if a hand has come out and taken yours.’

Musicians before this had occasionally described the physical abuse of a male child by an adult family member: Suzanne Vega’s ‘Luka’ is the first such song that comes to mind. Nonetheless, there’s something about the vulnerability, detail and directness of The Sunset Tree, its sustained investigation of this harrowing theme, that makes it a record of singular power for those who have been through the experiences it describes and to whom it’s dedicated. ‘Hast Thou Considered The Tetrapod?’ affirms two things simultaneously that are inarguably useful not only to this group of listeners - who have their own unique claim on the material - but to any teenager finding in music a conduit for whatever kind of emotional intensity they are still learning how to navigate in their own young life. The first is the condition of feeling like you are the only person on the planet, totally alone, ‘the last of a lost civilisation’; and then the feeling that that someone, or something, at least, has been here before, has experienced this feeling too, and someone else before that – an unbroken chain, reaching back into the depths of existence. I’m in my room with my headphones on, and I’ve never heard anything like it.

OK so look, I’m thirty-two years old, and I’m dicking around on the Internet. Specifically, I’m supposed to be writing about The Sunset Tree, and instead I’ve picked up a guitar and started improvising a song: ‘Catch me drifting slowly out of reach / The Venerable Bede of Venice Beach.’ That doesn’t really mean anything, but I suppose it gives a flavour of two things that are continuously on my mind these days: the history of the North-East of England, an area I moved to for work in an especially difficult time to build social networks and am trying to find roots in, and the Southern California cities and neighbourhoods I know only from the songs I spend much of my time thinking and writing about, and from a single week-long visit. Beyond that, it means that writing about The Sunset Tree is difficult. It’s a widely-acknowledged masterpiece, with huge personal significance for great numbers of people who have used it to alleviate, process and articulate their suffering; Darnielle has alluded to it being the work he expects to be remembered for the most. Geoff Sanborn shared its entry in his newsletter All Hail the Mountain Goats on Facebook with no other text but the caption ‘The big one.’

In terms of the band’s career, Darnielle modestly describes it as ‘a record that changed things for us,’ in part because it changed something about how the Mountain Goats operated. Having started out thinking of his songs as ‘dramatic monologues’ whose speaking character ‘exists only for the utterance,’ in the aftermath of Mike Noonan’s death, the songwriter now felt ready to take his listeners into a deeply personal place: ‘I went on tour a month or two later, and stuff started to crack open … I started to feel free with my feelings … to know that the person who used to hurt you no longer can is very, very, very deep.’3 The successful experiment in incorporating autobiographical material that was We Shall All Be Healed paved the way, and its final track, the stomping ‘Pigs That Ran Straightaway Into the Water, Triumph Of,’ nods explicitly to the one place Darnielle’s recorded output hadn’t yet openly engaged with: ‘Even if I have to go to Claremont / Well I guess I’ll just have to go to Claremont.’

In a conversation during the live recording of the Jordan Lake Sessions, Darnielle frames the song as non-autobiographical, written ‘largely to amuse’ Peter Hughes, an actual Chino native, who shares vocal duties on the hook line ‘I come from Chino where the asphalt sprouts.’ I’m not dismissing any of that when I note that in a recent interview, Carmen Maria Machado suggested to Darnielle that ‘When you write something in the first person… the character has some relationship with you, but that relationship is usually unknown to the reader,’ and he built on the point: ‘And usually unknown to the writer, I would argue. Although I think all our characters and speakers are us, the writers, I don’t think we know what they’re trying to say about us.’ The character in ‘Pigs’ is at risk of going to prison – ‘Please don’t fit me for the orange jumpsuit’ – but prepared to resist this potential future in any way possible, despite the cost – ‘You’re going to do what you wanna do / No matter what I ask of you’ – even if going to Claremont is the only alternative.

It’s not difficult to find resonances here with Darnielle’s own situation in the late 80s, back in Southern California post-Portland, still dealing with substance dependency and attendant legal issues but determined to make something else of his life. On December 6th 1988, the 21-year-old drove away from a courthouse hearing he’d attended alone, without a lawyer, having ‘managed to duck a three-year prison sentence’; the charge was presumably related to the weekend Darnielle had spent in jail earlier that year, after which he’d been fired from his job at a Catholic-run Los Angeles AIDS hospice. The aftermath of that incident was the rock-bottom moment at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel on Crenshaw Boulevard, reimagined as a ‘bargain-price room on La Cienega’ in the song which opened Darnielle’s next album, creating a kind of diptych with ‘Pigs’ that functions as a fulcrum.

This record, it seems to say, will take things back further still than the dark days described on the previous, and what introduces us into that world is an image of unflinching self-scrutiny about everything that’s led up to the song’s here-and-now: ‘I looked myself right in the eyes … And down there in the dark, I can see the real truth about me / As clear as day.’ ‘You Or Your Memory’ turns on what feels like a real promise made in front of that mirror, one emphasising the previous track’s conviction that ‘I’m not headed southeast from the courthouse’: ‘Lord if I make through tonight / Then I will mend my ways / And walk the straight path to the end of my days.’ Having made it through that night, Darnielle made it through the hearing, too, which he vividly remembers as the day Roy Orbison died; in March 2020, to make Getting Into Knives his band decamped to Sam Phillips Recording, part of the family of Memphis studios in which Orbison had cut his own early singles.

Though by now there are probably a few Mountain Goats records I’ve spent more time with than The Sunset Tree, the place it holds in Darnielle’s journey as an artist – revisiting, as I’ve outlined, some of the most significant turning points in his journey as a person – means it has a scale as a document that has to be confronted, and something about that is inherently scary to me. In part, this inhibition reminds me of the way that the late actor Antony Sher described certain Shakespearean roles: ‘Lear is the Everest of parts’ (166) while Hamlet, ‘a romantic blond figurine in the gift shops of Stratford,’ feels so rarefied and alien to this performer’s gifts that he never considers playing him until ‘it’s too late’ (348-9).4 But writing about this pivotal album is also a case of what Oliver Burke, in his admonitory book on time management in the face of human finitude, Four Thousand Weeks, calls ‘the discomfort of what matters’: ‘when you try to focus on something you deem important, you’re forced to face your limits, an experience that feels especially uncomfortable precisely because the task at hand is one you value so much… you’re obliged to give up your godlike fantasies and to experience your lack of power over things you care about.’5

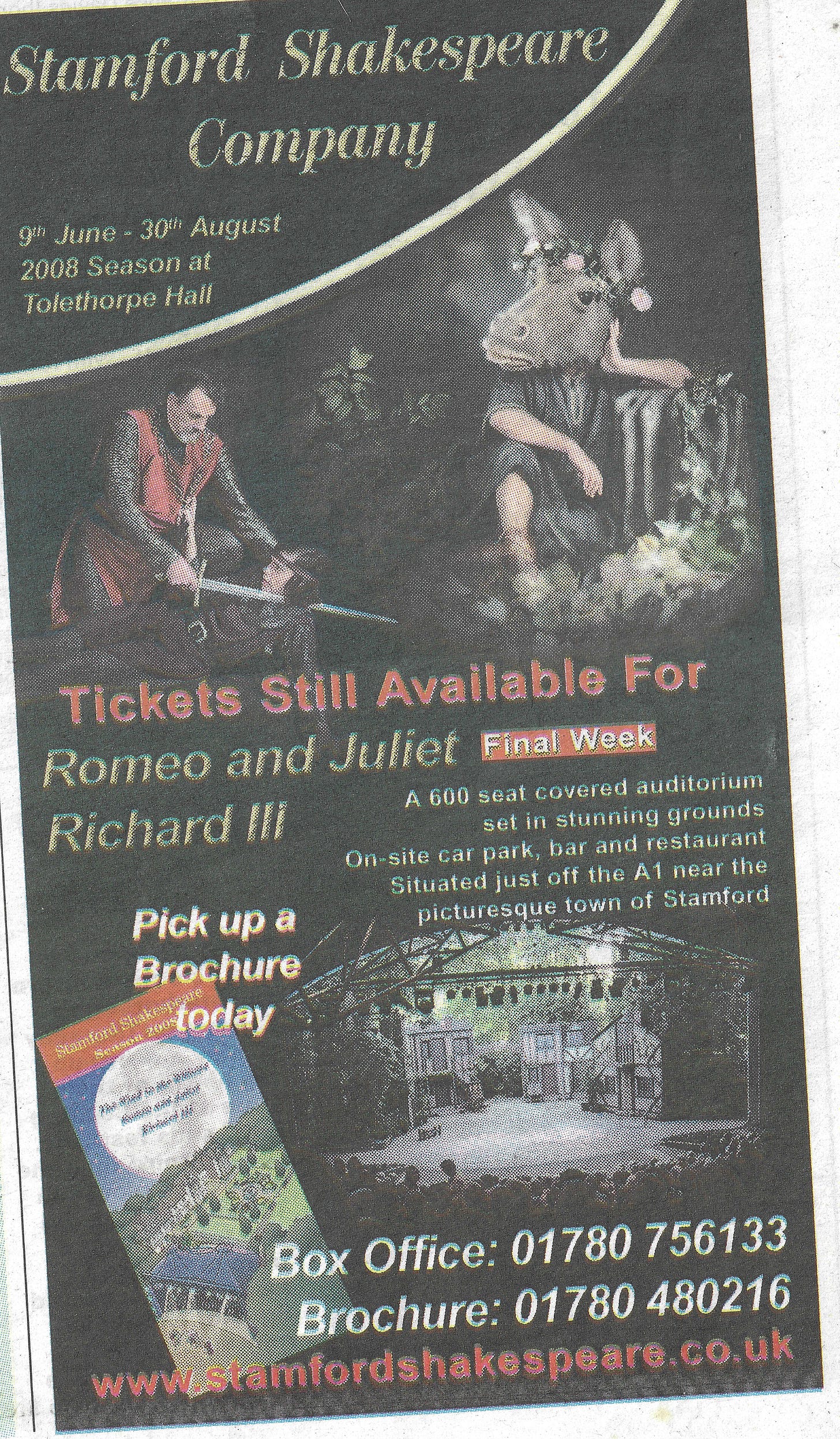

One of the godlike fantasies Burke outlines is the ability to do everything, ‘since every real-world choice about how to live entails the loss of countless alternative ways of living.’ At fifteen, I had many different paths ahead of me, and in retrospect I’m not sure that one seemed any more likely than the others. If you’d asked me, though, at least on some days, I’d have told you I wanted to be an actor. That was the year I played two small parts – Donalbain and Young Siward – in an amateur production of Macbeth, performed on an open-air stage in the grounds of a country house with a 600-seat auditorium covered by a tensile canopy. The Stamford Shakespeare Company boasted that ‘No performance is ever cancelled because of inclement weather’ – which meant, in practice, me lying on the ground in a coarse woollen tunic for the twenty or so minutes between the final battle and the curtain call while the August rains fell. I didn’t mind it.

I didn’t so much enjoy the three-hour rehearsals that went on for months beforehand, multiple nights a week, and I doubt my parents who I relied on for a lift did either, but the boredom of being a minor character, the overall feeling of slow, halting progress, gave me and my fellow young cast members something to complain about, which of course we did with relish. The company was fairly evenly split between school-age students and retirees, with the odd performer in their thirties and forties caught awkwardly in the middle (as you can imagine, this made for some complex dynamics in the casting of Romeo and Juliet two years later.)

Macbeth, who pinned me to the ground every night with a sword, was the husband of the Mayor of the town I went to school in, herself the sister of a slightly fearsome music teacher. One of the bumbling, septuagenarian attendant lords was a former Cambridge professor of Materials Science; to differentiate my two characters, I was encouraged to affect a fake disability by the assistant director, a man named Hubert with thick bushy eyebrows whose idea of acting seemed to be stuck in the days of Olivier. I liked the backstage gossip, the sense of camaraderie; we had T-shirts made in gentle mockery of the drawn-out way the lead actor roared the line ‘TIIIIIIIIIIME, thou anticipat’st my dread exploits,’ and generally, I’m sure, made a low-level nuisance of ourselves between the wooded glades and the wheeled scenery.

One of the other things I liked about it, of course, was the way it allowed me to be someone else in the eyes of others: nothing could make me feel more confident than to speak lines that were already written down for me, to have a script to disappear into when I opened my mouth. Though the experience still took place within my own body, at times I imagine it made me feel like I look in this picture: high in the air, hair flowing free behind me, almost weightless.

What acting offered, Sher noted of himself at this age, was ‘an amazing new alternative – you could hide away in public!’, your performance ‘as protective a capsule as four bedroom walls – and yet your refuge was somehow crowded with people, and clamorous with the noise of celebration’ (p. 24). At one point, early in the run of Macbeth, I even stood out in the car park after the show to see if anyone in the audience might recognise me, and was quietly taken aside the next day to have it explained to me that this wasn’t done. In all this, my ‘notions about acting’ were the kind Sher rejects, precisely because he had once believed them: ‘all about disguise rather than revelation.’ Quoting from Anthony Burgess’s translation of Cyrano de Bergerac, in which he once played the title role, Sher juxtaposes two styles of performance: one defined by ‘the casual dress of flesh,’ the other, which he came to favour, concerned with portraying ‘the visible soul’ (p. 110).

Few fifteen-year-olds probably want their soul on public display, and I don’t blame them, but the actor here asks a searching question: ‘How can you start pretending to be other people before you’ve become one yourself?’ Which makes me wonder if, by this point, I’d become a person in my own right. I’m sure I thought I had, but when I think about my mid-teens, I see only flashes of the self I recognise now, in amongst other faces, other voices, a cluster of assumptions and opinions I’d unconsciously imbibed and would take a good while longer to shake. At a village beer festival, I’m talking to a girl called Octavia who I met on the internet, who tells me she has an inherited title, and I get too fucked up and never see her again. I’m supposed to be at a friend’s house, but we’re staying out all night in Bourne Woods, sleeping on a platform in an observation tower, my parents furious with worry when I tell them the truth the following morning. On the driveway of our house, my Mum is laying into me for getting a mark in the 50s in a Maths exam. Upstairs, my Dad is asking if I’m gay because I’ve grown my hair long. In my bedroom we’re having an excruciating discussion about masturbation and computer viruses, and he keeps repeating this awkward little credo, which I think in its own way is supposed to reduce the shame of it: ‘You’re not the first and you won’t be the last.’

Sometime that year, I went to stay in a youth hostel in Cromer with four similarly long-haired friends, all boys, two of whom had nicknames based on their surnames: we smoked pot, badly, and listened to Dark Side of the Moon, and went free-scrambling up cliffs without adult supervision. Our group had bought an inflatable dinghy with a Union Jack design, but it didn’t have space for all five of us, and I found the idea of such a fragile vessel drifting out into the North Sea inherently alarming. So the other four went out, and I sat on the beach, until a concerned woman came up to me and told me that my friends were in imminent danger and that she’d called the coastguard. At the time it all felt like a lark, and it probably was: the next day we saw an A-board for the Eastern Daily Press with the headline ‘Boys in Sheringham Dinghy Drama.’ But even then, it occurred to me to wonder: why did they have the dumb, feckless courage I didn’t? Why was I the only one left waiting on the shore?

In other words, I was ready for something to come along that might help me start making sense of my life – for something that would call out to me as a listener, that would address me, asserting its claim on my attention. I would get this in literal terms from the lines which open the verses of ‘Dance Music,’ working like the bardic ‘Hwaet’ at the beginning of Beowulf, translated by Seamus Heaney as exactly this kind of casual ‘So.’ I’d get it from the long-held note at the end of ‘Broom People’ and the raucous howl at the end of ‘Dilaudid’ – both in their way speaking of the limitations of language in the face of more powerful forces.

But for the most part language here, once I’d discovered the Mountain Goats’ most recent album, wouldn’t seem that limited: quite the opposite. Its power to do things to the brain sparked and crackled in the casual inversion of ‘seventeen years young’; in a giddy, enigmatic tongue-twister about ‘the special secret sickness’ (whatever that was); in the writer’s daring appropriation of stories that I thought I knew (Romulus and Remus, Joseph and his brothers), and his creation of new, indelible metaphors (‘wringing out the hours like blood-drenched bedsheets’). After a while I’d start to turn over, too, ‘like a living Chinese finger trap,’ Darnielle’s willingness to veer from the adrenalinising high road into wholly unexpected emotional byways. All of these things would offer me, in their own ways, something like a hand hauling me up onto the dry land of self-identity. I didn’t know that yet. My finger hovered over the button. I opened the door.

All of this -

All of this -

All of this before I got there.

A note on future instalments

Today’s entry marks the mid-point of this project, and I thank any of you who’ve been listening thus far from the depths of my heart. This instalment will be the end of the current season, and when I start work on the second half of the book in Portland later this summer, future newsletters will be a little different. I’m not sure exactly what they’ll look like yet, and I’d value any suggestions you have if you want to get in touch!

This week, Richard is getting into J. L. Carr’s A Month in the Country.

An attentiveness to deep time has not been exclusively Darnielle’s preserve within modern indie music: on ‘Must I Evolve?’ Jarvis Cocker recently took listeners over six minutes from the big bang to ‘the mind in the cave’ to the feeling of being ‘out of your mind at a rave,’ while Jens Lekman’s ‘How We Met (The Long Version)’ recounts the story of evolution from the ‘Cambrian explosion’ to the emergence of ‘furry mammals with big beautiful brains’ capable of falling in love with each other over a borrowed bass guitar. Few artists, however, have explored this seam quite so thoroughly.

Bede. A History of the English Church and People. Translated and with an introduction by Leo Sherley-Price, revised by R. E. Latham. Penguin Books, 1968, pp. 127-8.

In Marc Maron, Waiting for the Punch: Words To Live By From The WTF Podcast. Flatiron Books, 2017, p. 40.

Antony Sher. Beside Myself: An Actor’s Life. Revised edition. Nick Hern Books, 2009.

Vintage, 2021.

Share this post