NOTE: A lot of today’s instalment is about what life was like for queer teenagers experiencing homelessness on the streets of Portland in the 1980s. An organisation that serves this community today which John Darnielle himself has recommended is p:ear, which stands for Project Education, Art and Recreation. While I was in town, programme director Tony Martinez was kind enough to give me a tour of the building and told me about the amazing work they do, helping young people to get anything from socks and basic hygiene products to food service qualifications and opportunities to sell their own artwork. It all starts with looking at ‘youth as youth, intentionally developing relationships’ as the basis for mentorship, rather than a model centered on transactions or case management.

I don’t charge for any of my work on this project, but if you’re enjoying the newsletter you might like to donate to p:ear - you can do so at pearmentor.org/donate. Or if you’re in the UK and want to give locally, the charity AKT works for ‘safe homes and better futures for lgbtq+ young people’: you can donate to them on akt.org.uk/appeal/donate. If you make a donation to either organisation, tag me on social media - @notrockyhorror on Twitter or Bluesky, @thirty_years_later on Instagram - to let me know, and I’ll post you a photo. In Portland I didn’t quite manage to ‘shoot a roll of 32 exposures’ - disposable cameras these days seem mostly to come with rolls of 28 - but I do have spare copies of a good few pictures from my trip which I’d be happy to post out in exchange for your generosity if you get in touch.

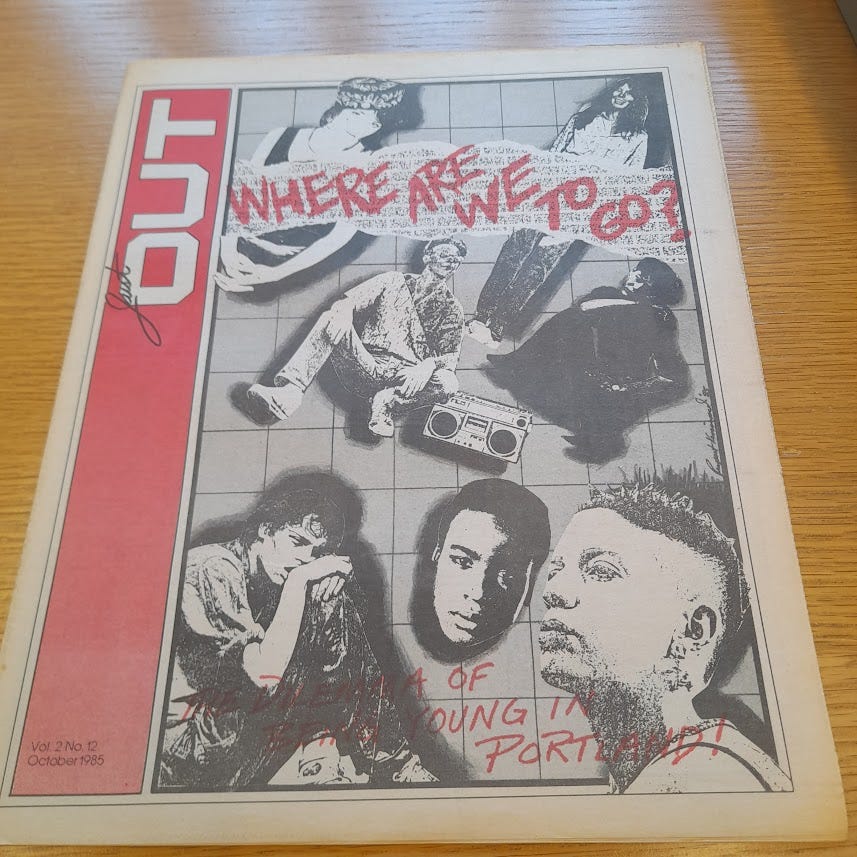

Are you ready for the wild style? If you happened to pick up the November, 1985 edition of Just Out - a Portland publication which called itself ‘Oregon’s lesbian and gay newsmagazine’ - and found yourself looking at a black-and-white advertisement for ‘an all-age gay nightclub,’ operating ‘Before-hours & After hours’ and open until 4 a.m., you might have found yourself asking exactly that question.1 The City Nightclub ad features a cast of pretty cool-looking cartoon characters, dancing and mingling, sipping frothy drinks, sitting around tables the tops of which, on closer inspection, are actually vinyl records - some even have records as their headphones, their earrings, and the lenses of their dark sunglasses. According to the artist Leela Corman, the resemblance is a coincidence, but they remind me a bit of the milling crowd on the cover of Goths (2017).

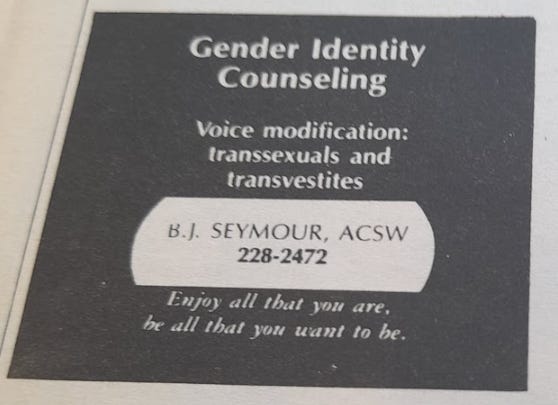

A different ad, printed a month earlier, promised ‘the best in music, sound and action’: opposite the text was a deliberately provocative image of a man holding his trenchcoat open, across from a DJ whose eyes shoot laser beams, unless the beams are coming from beneath the trenchcoat - it’s difficult to say. ‘Expose yourself,’ the heading reads, ‘to the City Nightclub’ - you’ll find it at 624 S.W. 13th, between Morrison and Alder. This was a venue for ‘outrageous shows’ and masquerade balls, which held a Coronation every year for drag performers who were given the titles Rosebud and Thorn. Its advertising ran alongside reviews of Gus van Sant’s Mala Noche; event listings for ‘a lively discussion on Lesbian S/M at the Lesbian Forum, in the Great Hall of Westminster Presbyterian Church’; copy for the Hard Times Adult Center (VHS videos on sale for $18.95); and voice modification training offered by gender identity counsellor B. J. Seymour, with the tagline ‘Enjoy all that you are, be all that you want to be.’ The ‘Wild Style’ itself is never defined, but it’s heavily implied that when you’re ready for it, you’ll know.

I don’t know when exactly John Darnielle - who claims, at the time, that he never took his own dark sunglasses off - decided that he was ready for the wild style. He might not have seen this ad for the City, or any of them, although according to proprietor Lanny Swerdlow, the venue in the basement of the Danmoore Hotel was ‘a real underground club. We didn't have a sign out front saying anything. So you either knew the address or you weren't gonna find [it].’ But it’s certainly the case that the nine months he spent in Portland wouldn’t have been the same without it. A document in the collections of the Gay and Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest - held in the air-conditioned top floor library of the Oregon Historical Society, where I also consulted the issues of Just Out I’m referencing - describes the space as ‘a safe and accepting environment for gay and lesbian youth’ in the face of ongoing and systematic police harassment.2

And although the teenage Darnielle didn’t share a sexual orientation with the community he got to know there, the City also offered him a place of safety and shelter, as well as ‘the best sound system in Portland & possibly the entire PNW.’ Through the winter of spring of 1985 and 86, the club’s strobe-lit dancefloor would thump and reverberate to songs like Nina Hagen’s ‘Smack Jack,’ ABC’s ‘Be Near Me’ which ‘packed the floor and made us all love life together for the duration,’ and Shriekback’s ‘sneering, knowing’ ‘Nemesis,’ the latter cutting directly to the core of the ‘young permanently jaded secretly-ecstatic and highly-at-risk’ version of himself who frequented the venue.

The origins of the club were deeply bound up with a group of young people who in many cases ‘society [has] written off - and who [have] in turn written off society.’3 Owner Lanny Swerdlow, who called himself ‘the token homosexual’ on ‘the Central Police Chief’s Advisory Council’ in the early 80s, described how ‘every meeting people would complain about these kids hanging out’ around the corner of Southwest Third Avenue and Taylor Street - an intersection known as ‘The Camp,’ and later transposed in Darnielle’s writing to ‘13th and Taylor.’4 Nearby was ‘The Wall,’ an area on the east side of Pioneer Courthouse Square which had become ‘the center of street-level drug activity in downtown Portland.’ The name came from a brick wall around a parking lot which had been knocked down specifically to dissuade young people from gathering there; the square itself contains the ‘red steps’ on which Darnielle’s narrator sits to smoke a cigarette in ‘Wizard Buys A Hat.’ This summer, at an outdoor show in Portland, he played that song to a crowd sitting on the same steps: an outcome which, from the perspective of the figure singing, convinced that ‘this town’s gonna put a quick end to me,’ must have seemed impossibly, unbelievably distant.

‘Wizard Buys A Hat,’ live at Pioneer Courthouse Square on 2023-08-09, taped by yltfan.

A three-part series of reports in The Oregonian newspaper in September 1984, a year before Darnielle arrived in Portland, paints the scene: ‘Many kids at the Wall, known as “rockers,” wear hard-rock T-shirts, spiked bracelets or fingerless leather gloves’; regulars exchange hugs, handshakes and ‘nods of recognition,’ while some of them carry portable radios, ‘blasting guitar music sounding more like a chainsaw cutting through metal.’5 These kids ‘never did anything wrong, really, but if you put a hundred teenagers on a street corner, everyone panics.’ One day, as Swerdlow tells it, six of these young people ‘came to [him] and said they wanted to open a club’: he contributed the initial capital, ‘and the kids spent fourteen-hour days for a month cleaning it and setting it up.’ The City changed locations many times, but always served this key constituency of young people, three-quarters of them under 21, who ‘didn’t have anywhere else to go.’

Many of its patrons lived on the streets, although its owner ‘had a reputation for hiring and finding housing for those who really needed help.’6 Those Oregonian reports present a bleak picture of life for the 200 or so ‘hard-core street kids’ then estimated to be sleeping rough there. One social worker describes them as ‘“the runaways and throwaways’” of society … “used, abused, scared kids”’ for whom ‘life at home is impossible’ to return to. While some came from the local area, others had arrived from elsewhere on the West Coast along what was known as “the I-5 runaway circuit,” and further afield. One 18-year-old, Karla, told the journalists that ‘downtown is a family. The kids downtown are family. Everybody’s got to help each other, or nobody gets nowhere.’ That camaraderie ranged from ‘pool[ing] money to rent a cheap hotel room together downtown,’ to taking down the license numbers of the cars young people engaged in sex work were getting into.

The teenagers in downtown Portland at this time did have some resource to The Greenhouse: ‘a resting place’ near the Camp at 322 S.W. Yamhill Street, named after state congresswoman Edith Green. Open between 3:30 and 11pm every day, the refuge could provide under-18s with ‘a meal, clothing, counselling and school preparation,’ as well as job referrals and assistance in filling in financial aid applications. One of the Lutheran Church volunteers who cooked for the shelter gave an indication of the menu: fruit cobblers, oatmeal cookies with peanuts and raisins, “Tuna Pasta Surprise.” The drop-in centre was set up by the Salvation Army, however, and so as Linnea Due framed it, in her influential book Joining the Tribe: Growing Up Gay & Lesbian in the ‘90s, a certain amount of moral judgement was difficult to avoid.7

I picked up Due’s book at Powell’s bookshop in Portland, which Darnielle tweeted he ‘would haunt… for hours & hours on rainy days’ during his time in town. The author observed that by the 90s, ‘estimates of how many street kids are gay and lesbian range from ten to fifty percent, depending upon whom you ask’; as such, there was a very real need for affirming places like the City, which continued in its unique role throughout the 80s and into the following decade, in a new location.8 Just Out noted that as well as boasting ‘some of the best and most recent music in town,’ the City’s foyer offered many kids a much-needed space for ‘just sitting in the front room talking, discussing circumstances of various emotional contests as if it were half time in a peculiar sort of game.’ Due interviewed three of the club’s 90s patrons - young men who had all ‘been cast out in some fashion, survived through sheer grit,’ and now found themselves ‘engaged in a search for kinship, definition, and meaning.’ Even by 1994, she described it as a place ‘under siege’ which ‘exists nowhere else in the country,’ designed specifically to serve a community ‘stigmatized to such an extent that being a member marks you as not being whole.’9

To illustrate the very real threat bound up in that social stigma, Due begins her narrative with a scene set not in Portland, but Richmond, California, where she joins an action organised by the East Bay chapter of Queer Nation. Outside a ‘crowded mall,’ the young activists gather wearing ‘jackets bedecked with decals (DYKE, QUEER, FAG)’: inside, and ‘exhausted’ after a day of confronting pretty open hostility, Due and her subjects meet up to ‘regroup’ in a ‘sunken conversation pit’ which turns out to be ‘circled by balconies three stories high.’ With a certain numbed precision, Due recounts what happened next:

Those balconies were soon mobbed by people, most of them also under twenty-five, many dangling over the railings to better pelt us with abuse, hard candy, and anything else they could grab from the nearest trash cans. There were just twenty of us, a couple hundred of them, and the hate and passion on their faces were all-consuming … In my dreams I saw those tiers of twisted faces looming over me, eyes bright with malice.

Due is surprised to find that the members of Queer Nation nonetheless consider the event ‘a success’: in response to their community’s newfound visibility, the people of Richmond have been baited into revealing ‘how they really feel.’10 Looking that hatred clear in the face, they’ve experienced their own sense of exhilarating clarity. To Due, this is nothing short of remarkable. But reading that passage, it did sound like a scene I’d encountered before:

Well they come and pull me from my house

And they drag my body through the streets

And the sun’s so hot I think I'll catch fire and burn up

In the summer air so moist and sweet

‘Heretic Pride,’ in John Darnielle’s telling, is a song about ‘really enthusiastic role acceptance’: specifically, the role of the martyr. Assuming the persona of a figure who really ‘wants to be killed’ - and here let’s not forget that every heretic is usually, by his own definition, a true believer - Darnielle goes on to imagine the scene. ‘You start to say to yourself, “When they kill me, I hope my blood gets on them. That’s going to be awesome, to see the gore from my innards spattering their guilty, filthy faces as they destroy me from top to bottom.”’ This is its own kind of recognition scene: the narrator seems to be saying, I see your hatred, I know it intimately, and I want you to know that I am capable of meeting that strength of feeling and looking you dead in the eyes with a corresponding fervour.

In a somewhat bizarre 2005 interview conducted entirely in haiku, Darnielle offered the following gloss on ‘Pale Green Things’ to Kevin Sampsell for Willamette Week: ‘So many sides to all things! / Big blue California sky.’ It’s a quality I see across so many of his songs: a commitment to looking really hard at something until another side of it is not only visible, but bright and shining. Something like this, for instance, must be what animates the couple in ‘Evening in Stalingrad,’ sheltering in a basement from the Soviet secret police, who declare ‘we are warm in our hidden heat down here / We got stars in our eyes tonight.’

What if, the narrator seems to be saying here, when my neighbours came and pulled me from my house, I wasn’t cowed and quivering, but fucking exultant? What if I told the whole thing in a reasonably dry, neutral tone, with a pause for your reactions between each line, as if I’d somehow survived the impossible and was looking back and ‘laughing like a child’? What if, on the day my skin was torn by being dragged across jagged ground by a swelling crowd of people who lived side by side with me, who now wanted to see me publicly executed in the town’s ‘main square,’ I was thinking about how nice the air felt, the sweet scents of honeysuckle and jasmine? Unlike in ‘You’re in Maya,’ the things of this world offer a solid, grounding comfort when the speaker’s fellow citizens are trying to cast him out of it: the sensory impressions they give off seem stronger and more meaningful than the prospect of imminent death.

This reclamation of a narrative of suffering is, of course, not unique to ‘Heretic Pride’: it pervades Darnielle’s songwriting. One of its strongest expressions comes in a song written in 2009, a year after ‘Heretic Pride’s release: ‘Everybody hates a victim / Who won’t stop fighting back,’ John sings on the live-only ‘Hail St. Sebastian.’ The two lyrics have recently been connected in a beautifully-written round-up of ‘10 Mountain Goats Songs, Ranked by Transness’: the author, E. E. Murray, describes how the latter ‘embodies the pensive defiance of confronting hatred with grace,’ while ‘Heretic Pride’ itself locates within that martyrdom the blazing power of ‘transfiguration’: ‘a moment, however brief, where you can be you, the fullest, most effulgent, most fiery you there can possibly be.’

On the song’s release, Darnielle disputed that it had any clear political reference, but the adoption of ‘Heretic Pride’ by the trans community - not least in this well-loved comic by Leslie - is something its singer has clearly taken to heart. Introducing it onstage at Wooly’s in Des Moines, in his former home state of Iowa, he asserted: ‘When I sing this song lately I think of a number of friends of mine who in recent years have felt that the target that is on their bodies twenty-four hours a day has gotten bigger.’ At a recent show in Austin, Texas - a state which The Texas Tribune notes is both ‘home to one of the largest trans communities in the U.S., and now ‘one of 18 states that restrict transition-related care for trans minors,’ with consequences some have described as ‘forced detransitioning’ - he made a still more explicit statement of support before launching into the performance: ‘Trans rights now.’

Speaking about his time at the City Nightclub in a Portland concert in 2022, John describes 1985-6 as ‘a time of profound fear and anguish’ for anyone who was ‘male and queer or queer-adjacent’: his friends in the community which ‘nurtured’ him were rapidly dying, and ‘the US government did not care - the President would not say the word AIDS,’ while his right-wing supporters acted as if young queer Americans deserved to die for their sexual practices. An editorial in a 1984 issue of Just Out had sounded the alarm: ‘If Reagan wins [again] in November, you will be stripped of the right to personal choice because he will say that the “mandate” given him by the “majority” will allow his party to deny minority rights.’

The same publication drew attention in 1986 to the fact that the administration was proposing substantial year-on-year cuts to the federal budget for AIDS research and treatment. At the same time, its pages testify to the spread of the disease: by May, one ministry was advertising a weekly liturgy named ‘Mass in Time of AIDS,’ while safe sex messaging from the Cascade AIDS Project was taking up greater and greater space on the paper’s pages. On Sunday June 14th 1987, despite some trepidation over the legal consequences of sharing this content with its underage clientele, the City Nightclub itself offered ‘A Special New Attitudes Training’ sexual awareness workshop, with Lanny Swerdlow taking the view that ‘we’re not gonna let our gay kids die for a lack of information.’

E. E. Murray observes that many of the songs in which she finds trans resonances belong to the long list of Mountain Goats compositions which ‘embrac[e] monstrosity.’ ‘As if speaking directly to those who call any living thing a monster,’ the 2005 non-album track ‘The Mummy’s Hand’ draws on Shylock in The Merchant of Venice to ask ‘If you prick us, don’t it sting? / If you kick us, won’t it hurt?’ If you spend enough time with the demonised, perhaps it's a pretty straight shot to starting to wonder how the actual demons feel: even that phrase, ‘the wild style,’ feels like a reclamation of an external label, reframing as stylish the perception that you are in some way savage, outside the bounds of society, other than or less than human.

And this attraction to exploring the monster’s side of the story can be found across Darnielle’s catalogue: according to his copy for some recent tour dates, the Mountain Goats’ songs ‘often seek out dark lairs within which terrible monsters dwell, but their mission is to retrieve the treasure from the dark lair and persuade the terrible monsters inside to seek out the path of redemption.’ Wryly quoting Axl Rose, he identifies ‘What’s so terrible about monsters, anyway?’ as ‘the question the Mountain Goats have been doggedly pursuing since 1991.’ You can hear it all the way from 1995’s ‘Neon Orange Glimmer Song’ (‘I am a monster - I can’t believe the thing I’ve done’) to ‘New Monster Avenue’ on the album immediately preceding Heretic Pride (‘all the neighbours come on out to their front porches / Waving torches’). Although I don’t have space here to say any more about it than this, Darnielle’s first book, which came out the same year - a novella he snuck into the 33 ⅓ music criticism series about an institutionalised teenager’s deep connection to Black Sabbath’s Master of Reality - aimed to honour the young patients its author saw during his time as a psychiatric nurse, dismissed by mainstream society in similar, familiar ways.11

Heretics and monsters aren’t exactly the same thing, though the way the crowd in the song pulls the speaker from their house sure makes it seem like they see it that way. In any case, it’s clear that the dynamics of Christian vs. pagan, and of the mainstream church vs. the fringes of belief, underpin much of Darnielle’s interest in these alternative perspectives. Raised in ‘the Catholic tradition’ which used ‘pagan’ as ‘‘a garbage-bucket term for all the people who weren’t in the Catholic church,’ Darnielle found himself increasingly drawn to the stories of these ‘living human beings persecuted literally for being themselves.’ Identifying our own time as one of ‘rising fascism,’ he saw a connection with present-day threats to ‘marginalized populations,’ and a ‘sense of urgency’ for writers with privilege, like himself, to address that climate. Writing about those who the Church had marked as outside its boundaries felt to him like a more ‘genuine’ way of accessing these ideas than trying to write ‘early Billy Bragg or early Bob Dylan–type stuff.’ His religious upbringing certainly factored into this approach in some way:

My work, for sure, my whole life pulls a bit from Christianity. I relate to people who get over who aren’t supposed to, people who survive who weren’t expected to. That’s the stuff that’s always spoken to me. That’s why you wind up cheering for the bad guy a lot of the time. It’s very easy to go, “How come no one asked him, ‘How’d you get this way?’”

You can hear the spiritual inflection of this question in the original title for the Heretic Pride album - ‘The Vision As It Appeared to the Serpent’ - and in songs like the near-contemporary ‘Supergenesis,’ which inhabits the actual moment described in ‘Genesis 3:14’ when the serpent in the Garden of Eden is cursed to crawl on its belly all the days of its life, all the while dreaming of its return: ‘someday, someday, the call will sound / And we all, we all are gonna get up from the ground.’ In live performance with co-writer Kaki King, it calls forth something akin to one of Darnielle’s key influences, The Birthday Party, channeling that sense in the young Nick Cave’s voice of a figure quivering hopelessly on the edge of damnation.

I’ll return to these ideas in greater depth in the next episode, looking at ‘Psalms 40:2’ and the Mountain Goats’ most explicitly religious album, The Life of the World to Come. But Darnielle’s affinity for monsters seems to exist outside of this dynamic, too, and to go back a long way. In the liner notes for 1999’s Bitter Melon Farm, he recounts a formative childhood experience: eight years old, in front of his grandmother’s television, ‘seated crossed-legged way too close to the screen,’ and watching an attempt to set the water speed record at Loch Ness. The programme’s narrator is presenting a theory that ‘the monster was angry about the loch being too noisy and crowded all the time, and had intentionally upset this guy's boat,’ one underscored by the footage zooming in ‘on a small dark disturbance on the already dark water,’ over slow, minor-key music ‘punctuated by shrill strings’: all of this to depict the Loch Ness monster ‘as somehow dangerous,’ a concept which Darnielle claims ‘hadn’t ever occurred to me at all.’

The semi-autobiographical narrator of the closing section of Devil House, meanwhile, recalls a childhood game he played with the young Gage Chandler called ‘Frankenstein’s Revenge,’ in which one boy ‘plays the monster, pulling at imaginary chains that bind him to the garage door, while the other plays the scientist or his misshapen assistant, mocking and tormenting the creature until all hell breaks loose’ (362): ‘there’s no game,’ Gage himself adds, ‘if he doesn’t break the chains.’ This leads Gage to a further reflection, on the letters he’d receive from the character based on the young Darnielle: ‘you used to write me about the movies you were watching,’ late at night, on the black-and-white TV his parents let him keep in his room: ‘it was always monster movies.’12

Reflecting on the ‘short but extremely important period’ he spent in Portland, as a patron of the embattled City Nightclub, the theme of monstrosity began to preoccupy Darnielle in a different way. At a 2017 San Francisco show, the presence in the audience of one of his elementary school teachers leads him to reflect on his childhood self - keen on the fantasy world of dragons and unicorns - and the transitional teenage period which followed, in which he began to ‘adopt … a hard and dangerous shell.’ This shell assisted him in ‘the process of trying to bury the good young me who had been under assault for a little while,’ as a result of which Darnielle experienced the ‘unfortunate tendency’ of wanting to ‘join in the spirit of your attackers,’ to ‘become the person that the people who are against you are telling you actually are down to your core.’

And to hear it from one of Darnielle’s undergraduate mentors, there was another key turning point. Barry Sanders first taught at the University of Southern Illinois, in Carbondale: he was hired by the novelist John Gardner, who one day said to his protegé: ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting to write a book from the point of view of the monster in Beowulf… and next thing I know he’s written this book, this novel, called Grendel - a copy of which I give to young John Darnielle later on, like in another lifetime, right?’ In class at Pitzer, Barry had been recounting a story about Gardner getting arrested for drunk-driving a motorcycle in the early morning the same day he was meant to give a keynote speech at the Breadloaf Writers’ Conference. When the highway patrolman heard the novelist’s name, he ended up letting Gardner off with a warning, in exchange for an autograph: Grendel was a book which saved his life.

In response to this story, Barry told me, ‘I can still see John Darnielle just.. becoming alive.’ The idea ‘of turning something around, not of telling the story from the point of view of this hero, you know, named Beowulf, but of the so-called villain, the so-called other side really appealed’ to his student, ‘because in point of fact, in truth - he was on the other side for a time, kind of gobbled up and spit out by civilisation. So lots of these songs are told, I think, from the point of view of Grendel, not of Beowulf - not of the person in charge, but the person who’s been charged.’ Comparing Darnielle’s writing to prison literature, Barry praised its qualities of ‘being able to speak from the point of view of the outcast who has the truth.’

In October 2008, I took up a place at Brasenose College, Oxford, to study for a joint honours degree in English and French: as a young white man at a prestigious university, I was about as far as it’s possible to get from the image of a person spat out and monstered by their own society. A certain kind of etymological quibbling was central to the ways we were encouraged to start thinking differently about literature, and early on in the course I remember my medieval English tutor, referring back to Grendel, drawing our attention to the shared root underlying ‘monster’ and ‘demonstration’: how what was considered grotesque or unnatural was also what was marked out, pointed at, put on show. I found the overlap between the concepts fascinating, but I’d never read Gardner’s Grendel. After speaking to Barry, I went back to Powell’s and got my own copy to follow up the thread.

When we first meet him in Gardner’s narrative, Grendel depicts himself as a ‘pointless, ridiculous monster crouched in the shadows, stinking of dead men, murdered children, martyred cows,’ holding up a ‘defiant middle finger’ to the world.13 But he didn’t always understand himself this way, and one of the early memories he recounts seems particularly significant: the time he heard a skilful, blind ‘Shaper’ singing to a harp, his ‘ear pressed tight against the timbers’ of King Hrothgar’s meadhall.14 The Shaper’s singing, about the history of Hrothgar’s people, causes men to weep ‘like children,’ and leaves Grendel’s mind ‘aswim in ringing phrases, magnificent, golden, and all of them, incredibly, lies.’ He is stunned by the power this art can hold: ‘the man had changed the world, had torn up the past by its thick, gnarled, roots, and had transmuted it,’ so much that even those who had been present for the real stories the songs are telling ‘remembered it his way - and so did I.’

‘Filled with sorrow and tenderness’ and ‘tormented’ by ‘the honeysweet lure of the harp,’ Grendel experiences for the first time what it means to be a ‘ridiculous hairy creature torn apart by poetry … I gnashed my teeth and clutched the sides of my head as if to heal the split, but I couldn’t.’ The anguish this causes is not only due to his exclusion from the holy world of music, but because of the place the singer has assigned to Grendel within his own cosmology: not a creature driven by pure, animal hunger, but one half of ‘an ancient feud between two brothers which split all the world between darkness and light. And I, Grendel, was the dark side, he said in effect. The terrible race God cursed. I believed him. Such was the power of the Shaper’s harp!’, whose ‘sweetness’ Grendel is continually drawn towards ‘even if I must be the outcast, cursed by the rules of his hideous fable.’15

I don’t know whether or not John actually read the book that his tutor recalls pressing into his hands, but even the concept seems to have hit him hard, and the results seem to me much more empathetic than the still somewhat grotesque worldview in which Gardner’s prose revels. T. S. Miller, in an academic article exploring the song ‘Grendel’s Mother,’ observes that Gardner depicts the figure as a ‘loathsome, inarticulate, and decidedly animalistic primal matron, a “life-bloated, baffled, long-suffering hag” who “never speaks”.’ Darnielle’s song, however, exists ‘in soaring defiance of’ this framing of the character to which Gardner heavily contributed: ‘keen to give every monster its hearing-out,’ he focuses on the affective quality of her grief. In the image of Grendel’s body burning on the bier, we see ‘Grendel’s mother participating in the very same type of funeral rites that the Danes and the Geats perform for their own fallen heroes,’ and this kind of sympathetic levelling also colours the song’s approach to the theme of revenge: ‘when Grendel’s mother describes her approach to Heorot—”I come naked and alone”—Darnielle communicates her feelings of both bereavement and powerlessness, but also sets her on identical footing with Beowulf, “naked and alone” being precisely how Beowulf always insists on fighting.’

As an album, Heretic Pride was conceived of as something of a return to the roots of the Mountain Goats project from which the song I’ve just been discussing dates - notwithstanding the very evident new element of drummer Jon Wurster, best known from his work with Superchunk. Wurster’s forceful presence, however, meant that at first many listeners didn’t detect the ‘commonalities’ between these more fully-arranged songs and the ‘untethered … old Mountain Goats energy,’ which tended to keep its engine running on a mixture of ‘immediacy … anger and spite,’ much like the songs written for Bleed Out, to which Darnielle compared it in a Vulture interview last year.

Coming off of the focused, thematically-restricted Get Lonely, Darnielle was excited to work on ‘the first one-song-at-a-time no-theme record I'd done in forever’: one which felt like the early writing process of ‘the songs that became Hot Garden Stomp - every little minor obsession of mine just blowing up and possessing me for a day.’ One of those obsessions, of course, was the monsters - ‘satellite creatures in a big pantheon,’ also containing ‘cult leaders, dead singers’ and ‘ghost cowboys,’ which together form ‘this sort of personal cosmology I carry around in my skull.’ As he told Laura Barton in his first interview with a major British newspaper - one which I went out to buy a physical copy of on the day it came out; how’s that for a lost age? - ‘For the most part it was me going back to what I used to do, real method-acting stuff’ in which the songwriter took a range of ‘two-and-a-half-dimensional creatures’ and invested them ‘with all these things that you yourself bring to the table.’ ‘If I'm in any of these songs,’ he observed, I'm hiding’ - which might, of course, be its own route to self-revelation.

A scintilla more mature than in my early encounters with Get Lonely, I don’t remember spending quite as much time looking for Darnielle himself in the new music. Pitchfork reviewer Zach Baron, though a little confused about the previous record, correctly observed that here the singer’s ‘"I" is once again someone else,’ inhabiting the kinds of characters which make its faster tracks function as ‘seething throwbacks - taut, propulsive, paranoid, furious.’ After the more muted explorations of that first post-Sunset Tree release, Darnielle’s yell was back with a vengeance: in an NPR interview, he commented that ‘Lovecraft in Brooklyn’ was the loudest he’d ever sung on record, declaring himself ‘genuinely afraid’ of his own shadow with such gusto that Peter Hughes told him he could hear it when pulling up in the parking lot outside.

The classic Mountain Goats strumming pattern, as diagnosed by Wurster himself - DAHgadda-DAHgadda-DAHga - had also returned to active duty on ‘Sax Rohmer #1,’ which opened the record, as well as the title track and, in muted form, ‘In The Craters on the Moon.’ As Baron notes, it was now supercharged by a crack rhythm section which had proven itself more than capable of replicating ‘the precise, surging, and teeth-chattering headlong rhythm that is Darnielle's stock-in-trade.’ But there were also a lot of other things to focus on: no sooner had the Mountain Goats emerged in their new form as a fully-fledged rock band than they were keen to demonstrate what else they could do. ‘Tianchi Lake’ is twinkly and syncopated, while ‘Sept 15 1983’ pays tribute to its subject, Jamaican musician Prince Far I, by dipping its toes into the waters of reggae. Closing track ‘Michael Myers Resplendent’ has a theatrical sheen and swell which points the way forward to ‘Liza Forever Minelli’ and much of the piano-led work which followed. Meanwhile, the involvement of Jeffrey Lewis in the album’s illustrated press kit, and additional electric guitars from Annie Clark, brought the band closer than ever before to what it’s probably fair, if paradoxical, to call the late-2000s indie mainstream.

At the same time, the album was looking back, and not only in terms of the pulpy fixations of its lyrical content. Rachel Ware Zooi, with whom Darnielle had recently reconnected for their 2006 Pitzer performance, and Sarah Arslanian of the Bright Mountain Choir, contributed backing vocals to three songs, including the spectral and unsettling ‘Marduk T-Shirt Men’s Room Incident.’ Their presence on ‘New Zion’ is perhaps more representative: when our narrator lays down, dreaming by the water, in a world of cult-like signs in the sky, the voices surrounding his - after more than a decade away from the musical project whose inception they were part of, which has since gone through a number of evolutions but retained many of Darnielle’s founding fascinations - do indeed have the familiar-but-different quality of ‘old things made new.’

Heretic Pride might not be one of the Mountain Goats’ most coherent releases - and was probably never conceived as such - but its engaging blend of new and old had given me more than enough to chew on over those last few months between school and university, a big time of transition in my own life. In Ulverton, Adam Thorpe’s multilayered novel set across three hundred years of life in an English village, Violet Nightingale, a personal secretary, pleads with the egotistical cartoonist whose memoirs she’s been typing up to bury in a Coronation time capsule in the 1950s: ‘No more teenage years … You can only have seven, you know.’16 I’m conscious that you may well be feeling the same, and at this point I was similarly keen to leave my adolescence behind.

My family - transplants from Middlesex and London via Dublin - didn’t have the kind of deep roots in the local area which ground many of Thorpe’s characters in Ulverton. So mine was a rural childhood, but one almost entirely unconnected to the land: a state of affairs made possible by late twentieth-century, car-centric, commuter capitalism. In an essay I read recently by Geoff Dyer, on growing up as an only child from an ordinary background, the first in his family to go to university, I found a lot that I recognised: Dyer explores the strange sensation of cultural inbetweenness which higher education can generate, and also articulates a familiar sense of comparative isolation. Other than the people my dad saw down the pub, my parents didn’t really seem to have very many friends in the village. In the absence of ‘the remembered richness of working-class life that served as ballast’ for earlier generations of ‘scholarship boys,’ Dyer’s immediate community, like mine, ‘was just my mum and dad and me and the television.’ In fact, in our house, there were at least three: each of us settling in for the evening in our separate rooms.

Elsewhere, Dyer relates quiet afternoons with no peers his age in the immediate vicinity which ‘stretch[ed] out interminably,’ such that at points his memory of childhood ‘almost seems like a single afternoon of loneliness and boredom.’ I wouldn’t go as far myself, but when Morrissey sang about ‘spending warm summer days indoors, writing frightening verse,’ you can be sure I felt that. You can tell one thing for sure from this picture of me standing under the seventeenth-century hammerbeam roof of the college chapel, wearing a T-shirt covered with unspooling tape heads, even though I hadn’t owned a working cassette player in years: I thought that presenting myself as having a particular kind of interest in music was the fastest way to make a particular kind of friends.

What I hadn’t realised during my own warm summer days indoors in West Deeping, listening to Heretic Pride and daydreaming about where this new path might take me, was how deeply aspects of the record, and especially the sentiments which suffused its title track, were rooted in its writer’s formative experiences of a subculture I was completely unaware of. Although I first encountered John Darnielle’s songs through the lens of a fairly homogenous online indie scene where gatekeeper music bro tendencies were commonplace, queer culture had been foundational to their worldview from the project’s very outset. And over at least the last decade, as gestures like that Austin performance in the trans flag make clear, the Mountain Goats have engaged more and more overtly with a fandom which has grown to look a lot more like the kids at the City: ‘the kids who were my people back then & who will always be my people in my heart,’ as John wrote in a 2009 forum post.

In July 1986, not long after John Darnielle left Portland, the City opened up a second dancefloor, the Hollyrock Lounge, which prioritised ‘new wave and progressive music.’ Just Out described the punters who came to enjoy it: a ‘large, eclectic crowd of gay people,’ comprising ‘young men and women in Levi’s and tank tops, people in all styles and manners of black outfits, new wave afficionados in futuristic hairstyles and ‘60s clothing, [and] dancers in various let-my-body-feel-free outfits.’ Linnea Due elaborated on the scene in the City’s 90s iteration: the dance floor ‘pulses underfoot with flickering squares of colored lights’ while a mirrorball pulls ‘the fragmented colors and reflections up into a circling whole’; ‘punks in ripped jeans dance with smart girls in uniform’ next to boys with blue hair and piercings, ‘guys in partial drag with pouffed hair and glittery blouses’ and guys - on at least some of the corners - in ‘Chicago gangster gear.’17 If any of that resonates, tag yourself - and if not, take a look around the audience at a Mountain Goats show near you sometime.

If you do, of course, you might see me there - but you might be justified in wondering where I fit into all of this. One reasonable answer might be: on the outside, looking in. Nobody who attended the City Nightclub in 1985 and 86 would agree to do an interview for this story, which I think is fair enough. This was their own thing, in a place and a moment that must have been difficult to explain to outsiders: they didn’t know me, and I wasn’t there. What academics tend these days to call ‘subject position’ - the place in the world from which a person speaks - John Darnielle, in a podcast interview about his fictional take on true crime in Devil House, referred to as ‘standing.’ It’s a question I’ve been worrying at in various ways over the last few episodes, which I’ll state one more time here before, hopefully, getting on with it for the rest of the project: who was I to tell this story? What standing did I have to ask them to talk to me about this time in their lives?

The only honest answer is that the Mountain Goats led me to want to know more about the City: that it was one of the many places to which their music has taken me over the last two decades. I’ve been telling you here about some of the literal journeys my research has enabled, but perhaps no less important are the ways this music, and the community around it, have shifted my internal landscape. My own understandings of gender and sexuality are undoubtedly more mutable these days than the floppy-haired boy who first listened to ‘Heretic Pride’ fifteen years ago could have imagined, and though I can’t ascribe that purely to the songs, the binaries through which I grew up navigating the world seem less stable, less defining, the more time I spend around people who joyfully refuse them on a daily basis.

Every fan has their own pathway to the Mountain Goats: over the past eighteen episodes I’ve shared a lot about mine, but perhaps unsurprisingly, as the project develops, I’m feeling more and more drawn towards those other stories, and decreasingly keen on talking about myself at all. But what I do have to offer, I think, is a skillset I started developing as an undergrad in 2008: a literature academic’s instinct, not only to parse a text to within an inch of its life, but to piece together a narrative from scattered fragments, glimpses in the archive, looking for the ways small details can start to coalesce and pull together into a circling whole. Two more partial images, then, to give you a sense of where I was when I first embarked on the course of study that would one day lead me to the GLAPN archives on a British Academy-funded research trip ‘Exploring John Darnielle’s Portland’: a doormat in my bedroom with Che Guevara’s face on it; and my parents downstairs in the kitchen reading The Sun. In those first months at Oxford, it’s clear that the wild style wasn’t calling out to me, but it was still natural enough to occasionally wonder - as I still sometimes do now - how the hell did I get here?

Darnielle’s songs were already part of the answer. At the end of 2007, I found myself sitting in a plush red armchair for my college interview, wearing a second-hand tweed jacket which was doubtless my provincial attempt at moulding myself into a certain image. The effect was hampered, though, by the fact that, moments before being called in, another applicant had tripped over the garment hanging on the back of my chair and torn the front pocket nearly clean off with the heel of her shoe. The frayed threads and the fabric I had no time to tear off, flapping like a limp tongue, probably helped give my nerves something physical to focus on when I walked into the tutor’s room to discuss a poem I’d never seen before, my response to which would decide a big part of my future.

‘Over the shining mud the moon is blood,’ one line ran, and now - having batted off the usual informal opening questions (‘Is that a fashion statement?’) - the thick-eyebrowed Professor of French, Richard Cooper, was asking me to speculate on where that sort of imagery might come from. I had no context for the writer’s life, place of origin or literary lineage (later I discovered we were discussing ‘Till I Collect,’ by Guyanese author Martin Carter.)18 The moon is blood? Well, I rambled for a while: it sounds apocalyptic; it sounds almost Biblical… and eventually, some synapse fired in my brain, and I said something about the Last Judgement which seemed to be the kind of thing he and the other tutor were looking for, and after a few more questions they told me I’d be hearing from them soon.

What joined the necessary dots wasn’t anything I’d read at school, or anything I’d discussed with the other young poets on our private forums. It was a few lines of a song called ‘The Plague’ that had popped into my head, currently sitting in a miscellaneous folder on my hard drive - then-unreleased, because at the time of recording its singer ‘couldn’t find the tape’ to include it on the Mountain Goats’ Jam Eater Blues EP, though now accessible as the opening track on the first of the band’s pandemic-era Jordan Lake Sessions:

And rivers will all turn to blood

Frogs will fall from the sky

And the plague will rage through the countryside

Maybe eventually I would have got there some other way - as you’ll hear in the next episode, part of what spoke to me about the Mountain Goats’ music was its connection to a sense of turbulent Catholicism that I already knew intimately. But nonetheless, an image which one of their songs placed freshly in my mind got me through that interview, which in turn would get me a whole lot further than that.

After meeting Barry Sanders, I wandered around some of the downtown Portland locations on the itinerary I’d drawn up for my project. Many of them were essentially impossible to find. The Satyricon, site of the first (unrecorded) Mountain Goats live show in the city in 1996, and where John, ten years earlier, hadn’t been old enough to get in to see Celtic Frost, had been torn down; I’ve already mentioned the donut store dominating the Old Town block which used to house Berbati’s Pan. Capital has flooded into the city - though both sites still abut large homeless encampments - along with new residents attracted by the artisanal promises of the sketch comedy Portlandia, as I was told anecdotally and independently by two longer-term locals. For this, among many other reasons, ‘John Darnielle’s Portland’ doesn’t really exist.

There’s something compelling, nonetheless, about the quiet garden facing First Presbyterian Church on the site of the former Danmoore Hotel. The building was demolished in 2005 - its long-term residents rehoused through a low-income housing scheme - and the plaque set into the sidewalk doesn’t even mention another business which used to operate in the hotel’s basement. When owner Jim Fisher bequeathed the building to the church in his will in 1988, all business tenants were evicted. One of them - Lanny Swerdlow - found the development inherently absurd: ‘Leaving something like that to a church? Gimme a break.’ Only a church could afford to keep such a property vacant for so long, the lifelong atheist noted, ‘because they don't have to pay taxes.’ The space which used to be the City Nightclub was never rented out again - in time, it was redeveloped into an underground garage for parishioners.

The area had worse things coming. In recent years, shiny glass towers have gone up behind the site of the City: a new cluster of condominiums operated by Ritz-Carlton, whose website promises a location ‘beautifully situated among world-class shopping, entertainment and dining.’ A popular local food cart pod was displaced for the construction; residences start at $1.2 million. John Darnielle, on Twitter, commented that he could get his account suspended for saying what he would like to do to the new buildings: ‘Impossible to convey how different these neighborhoods were.’

Many of the people he knew in the area, in 1985-86, are now gone; many of the spaces important to them demolished or reshaped by corporate developers. At the centre of it all, where everything I’ve been describing happened nearly forty years ago, is a private garden. The space boasts elegant trimmed hedges and beautiful white roses, but on the day I visit it seems to be closed from every angle. Looking at it, I was reminded of ‘Divided Sky Lane,’ a non-album track from the In League with Dragons era which deals in its own way with lost friendships and lost spaces:

Five years now

Since they dissolved our crew

Since the fence went up

That I can't cut through

Grass grows high

On the former site

Of the carefully tended garden

We visited late at night

The song’s narrator is looking through a fence at a wilderness which used to be a garden; I’m looking at a garden which used to be something else entirely. On the wrong side of the fence, that distinction seems negligible. All that matters is that something is gone, severed: that except through writing, singing about it, there’s no way back to a place that isn’t there any more.

Thanks this week to Bluesky user @gothicdolphins, who pointed me towards high-quality, linkable online sources for the Just Out archives, and to Emerald Green, who helped me work out what I was trying to say in the back half of this episode. Emerald makes amazing unique-to-show stickers as well as great compilations of tMG live material, which you can find at https://www.thegemthecolor.com/thecompzone.

This week, Richard is getting into hot chocolate and marshmallows. I’m basic!

Some images are taken from my own photos of Just Out materials at the Research Library of the Oregon Historical Society; in the text, I’ll share persistent links that will take you to copies in the online collections of the University of Oregon Libraries; Eugene, OR. I’ve put full academic citations - e.g. Just out. (Portland, OR) 1983-2013, November 01, 1985, Page 18, Image 18, Historic Oregon Newspapers - on this link.

MSS 2988-1.

Linnea Due, Joining the Tribe: Growing Up Gay & Lesbian in the ‘90s (Anchor Books: 1995), p.16

Due, p. 25.

I was able to access these archives with a Multnomah County Libraries membership - if you don’t have a login which works on this material and would like to read it first-hand, get in touch and I’ll send you a pdf.

Due, pp. 23-5.

P:ear, in their work today, aims to start from a basis of equity. (Due p.23, 26).

Due, p.14.

Due, pp. xxxiii-v.

Due, pp. xiii-iv.

John Darnielle, Master of Reality (Continuum, 2008.)

John Darnielle, Devil House (MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022), p.362, pp.381-2.

John Gardner, Grendel (Gollancz, 2004), p. 1-2.

Gardner, pp. 29-30.

Gardner, pp. 35-8.

Adam Thorpe, Ulverton (Vintage: 2012), p. 309.

Due, pp. 27-8.

Martin Carter, Poems, edited by Stewart Brown (Macmillan Caribbean: 2006), p.16.

Share this post