September 8th, 2022.

I’m not sure which direction the narrator of ‘New Star Song’ is travelling in when, in one of the ‘untethered’ surges of wonder that characterise the early Mountain Goats style, he starts to think ‘about you as the lightning storms lit up all downtown Redding.’ But he must be on a different Pacific Coast Starlight service than the one I’m currently riding: his train ‘wasn’t due in till 11.45,’ a schedule seems positively civilized by comparison. I’ll be passing through the Northern California town around 2.30 in the morning, and taking a quick fresh air break at San Luis Obispo tomorrow afternoon, on my way to L.A. for a whistle-stop tour of some outlying regions with which readers might be familiar: Claremont, Pomona, and Norwalk. It’s a suitably anti-touristic coda to what’s been a packed, productive month of research in Portland, where I spent a lot of my time looking at places that weren’t there from 1986, but did manage to see the Rose Garden.

I thought I’d have found the time to update you before then, but between what I told the funders I’d be doing here (‘Exploring John Darnielle’s Portland’) and what I’ve been doing on my days off (exploring every birdwatching site I could get to on public transit), I’ve been keeping pretty busy. In my time in the city I’ve drafted two new chapters, and sketched out the outlines of a fair few more. A thirty-hour train journey with no WiFi seems as good a time as any to throw together something of a highlight reel, so what follows are some of the chunks of new writing, photographs, and archive discoveries I’ve felt most excited about over the past few weeks.

Snow Songs in Summer

A few snapshots from Portland.

Referring to the title ‘Snow Song’ in the liner notes for Bitter Melon Farm, John Darnielle calls it ‘a generic term with a very specific purpose. I use it when I've written a song whose mood reminds me, either lyrically or musically, of the winter I spent in Portland, Oregon, a season during which I almost died at least twice.’ On record, the Mountain Goats ‘Third Snow Song’ is pretty restrained and quiet, and that’s mostly the case when they play it in their 2003 Portland set at Berbati’s Pan, but in the way he hurls out the last two lines - ‘I hammered it against the ice’ - there’s something like the feeling I get from the chorus of ‘New Star Song’: untethered lightning. The site of this dynamic, edgy performance is now a strip club, while another part of the building has become a love-to-hate-it famous donut store with a security guard on the door and lines around the block.

Much of Darnielle’s time in the city took place in a cold winter (‘If you grew up where there’s sun it’s hard to move to Portland’), under the influence of powerful chemicals. Following the logic of the academic year, I’ve come to research it in high summer, and you can’t exactly ‘hide from the whipping rain’ in shorts weather. This year, luckily, has been a little more temperate, but in 2021, downtown Portland reached a high of 110 degree Fahrenheit, hotter that day than the Mojave Desert: a local meteorologist told the news, ‘in shock,’ that he ‘really wasn’t sure this was actually possible here.’ As well as the streetscape and the rent - Darnielle’s 750 square-foot ‘small room that got even smaller, a block away from the Willamette’ cost him $225 a month in 1986 and by 2018 was listed at $1125 - capital is changing the climate of the city, too.

Though the specific phrasing doesn’t appear here, and though Portland isn’t addressed in any direct topographical sense, a case could be made that Get Lonely is all snow songs. The album’s predominant settings are autumnal and wintery, a world of ‘slippery ice on the bridges,’ ‘pine trees frozen in the silvery moonlight,’ ‘wet leaves floating in gutters full of rain.’ Birds hovering in the ‘frosty air’ might seem to exhibit a perverse persistence - ‘What are they doing there?’ - but they at least elicit curiosity from the speaker of ‘New Monster Avenue,’ which seems like a more positive emotion than anything else they’re feeling.

The album’s characters might not consciously share anything like Thoreau’s quiet confidence about his ‘strange liberty in Nature,’ of his becoming ‘a part of herself’; the idea that ‘there can be no very black melancholy to him who lives in the midst of Nature and has his senses still’ is almost laughably inapplicable. Nor do they exhibit the individualism of the modern action movie hero, whose self-presentation as ‘just me against the sky’ - an image invoked twice on new album Bleed Out - makes him a distant relative of this vision of self-sufficiency. But in the absence of the author of Walden’s ‘serenity,’ these figures are still capable of ‘sympathy with the fluttering alder.’

Across Get Lonely, the natural world offers points of connection where human contact is lacking. The speakers’ urban lives bear out the truth of Olivia Laing’s observation in The Lonely City that ‘loneliness doesn’t necessarily require physical solitude, but … an inability, for one reason or another, to find as much intimacy as is desired.’ But in the cold corners of the built environment, plants are still blooming irrepressibly ‘from cast-off innumerable seeds’: wild sage and butcher’s broom, and further off, in the hidden places, ‘flowers that hide from the light on dark hillsides.’

When I was eighteen, I’d had the idea of doing a roadtrip across the U.S., visiting every place mentioned in a Mountain Goats song; blissfully ignorant of the country’s transport infrastructure, I imagined it would be possible - desirable, even - to do this on a Greyhound bus, like the one mentioned in ‘See America Right.’ I’d probably still do it if somebody paid me, but I now suspect that this would soon become an experiment in frenzied motion, a tiring box-ticking exercise. I wonder instead if a healthier project would be to try and see, in my lifetime, all the plants and animals mentioned in Darnielle’s work: the skate cases and black needlerush, the pelicans, the woods of northern pine.

‘Where does loneliness end?’, the singer asked in an interview with Akao Mika which accompanied the Japanese release of Get Lonely.1 He doesn’t give an answer. Down on Poet’s Beach, with the Willamette stretching out in front of me beneath the city’s full complement of bridges at sunset, I tried to picture loneliness as a small ship, sailing down the river and out towards the coast. I thought about the words of another lonely figure, far from Portland, back in Europe - the Tollund Man, taking leave of the only world he’d ever known: Goodbye, goodbye, goodbye.

‘We All Posted Very Intemperately In Those Days’

You might have noticed that throughout this project I’ve alternated between referring to the frontman of the Mountain Goats by his first and his last name, and I think those message boards played a part in that: in the late 2000s, John would post there himself, under his first name, and you could ask him questions, and sometimes he’d reply. It was what he’d been doing for years, after all, on specialist music message boards like Hipinion and I Love Music. ‘Pre-social media,’ these spaces were ‘where [he and his peers] hung out,’ he told Tom Breihan in a recent Stereogum interview, and where, as he noted drily, in a phrase likely to strike fear into the hearts of most seasoned enough internet users, ‘we all posted very intemperately in those days.’

‘I make myself available to people who like my stuff, and I'm open with them; it's one of the things that makes me different from other music dudes,’ Darnielle wrote on his own forum around this time. And in sharing demos and outtakes directly with fans here, Darnielle seemed to be creating a space apart from the more formalised schedules of album releases (especially in the rare years, like this one, when the prolific band didn’t have a full record coming out): a distribution channel which again emphasised the sense of a casual but committed, self-selecting community. Apart from my friend Catherine, a convert a couple of years younger than me who accompanied me to my first Mountain Goats gig at the Union Chapel in London, there wasn’t really anyone in my real life who shared my excitement whenever these recordings would surface, but despite - or perhaps because of - the fact that no one else was paying attention, each time it happened was nonetheless an event.

Two recordings in particular stand out as exemplifying this period of heady activity. In July 2007, two hundred Mountain Goats fans gathered for the ZOOP! Weekender, in benefit of the Farm Sanctuary animal rescue charity and taking place at one of their locations. Two days of the music I liked (including, on Sunday, an all-request show), camping at a farm in Upstate New York? To a seventeen year old - especially one with no way of getting anywhere near - this was practically Woodstock. Perry Owen Wright, who was also performing, reached for another comparison: a ‘compound full of tents,’ filled in turn with many of the distinctively ‘ardent fans’ which Wright had observed Darnielle’s ‘songwriting engenders’ and who were now sleeping ‘15 feet from his doorstep,’ could easily take on a ‘Jonestown-ian feel.’

Heidi Vanderslice, having noted a similarly ‘rabid’ response to this band’s music, asked John and Peter the same question for her TinyMixTapes write-up: ‘What was it like to be in such close proximity to your fans all weekend?’ Both gave genuine, warm-hearted answers. As Peter commented, ‘we’ve both been music fans for a lot longer than we’ve been guys who people come to see, so we don’t really think of ourselves as being any different’: away from the tiring ‘realities of touring’ clubs and their attendant time constraints, ‘we could just hang out all day and have fun.’ John, meanwhile, found the event ‘really relaxed and wonderful. It wasn’t really artist/fans. It was just a bunch of people hanging out on a farm and I happened to be providing the entertainment.’

It reminded him, in fact - at least by the ‘exhausted/sweaty/unhinged’ ending of the second set - of some formative experiences of music and community: ‘the early shows Peter & I used to do at Munchies where nobody cared whether you were really being good or impressive and the whole thing was just about everybody having stupid fun with each other.’ At that time, Darnielle was usually joined by Rachel Ware on bass and harmony vocals. Peter played there with DiskothiQ and Franklin Bruno’s Nothing Painted Blue: wrestling and Chino were the subjects of some of his and John’s earliest conversations. And years before joining the Mountain Goats in 2008, Jon Wurster also dropped by the venue with Superchunk, ‘on a spare night’ after their tour date in L.A.

The venue was a bar with ‘Astroturf carpeting’ in the back room of a sandwich shop in Pomona, which Hughes revisited for in an Autoweek piece about the mostly-shuttered ‘old haunts’ of his musical youth. Hughes offers readers a tour of the smog-ridden ‘part of California we referred to ironically by the name invented for it by vainglorious developers decades earlier: the Inland Empire,’ which comprised both Claremont, the leafy, college-centric ‘city of trees and PhDs’ in which Darnielle’s family nominally lived, and the less affluent Pomona. L.A. historian Mike Davis describes how Pomona in the 1920s ‘was renowned as the Queen of the Citrus Belt, with one of the highest per capita incomes in the nation’; by the 1980s, Darnielle recalls, it ‘led the nation in per-capita homicides,’ and for Davis writing in the following decade, it exemplified the ‘hundreds of aging suburbs … trapped in the same downward spiral from garden city to crabgrass slum.’

Most of Darnielle’s youth was spent right on the borderline between the two settlements, in the working class ‘faux-adobe ranch homes’ outside of the Claremont campus bubble on ‘the east side of town south of Arrow Highway.’ Munchies, situated in this unpretentious environment, had a ‘rec room’ feeling, Hughes wrote, where the artists mostly ‘performed for ourselves and each other.’ As Upland-based bands like Hughes’s made connections with Claremont/Pomona artists, like the Mountain Goats and Darnielle’s schoolfriends in Wckr Spgt, the bar became home for two or three years to ‘a scene so contrarian and suspicious of anything that smacked of industry hype that it wouldn’t even admit to being a scene.’ This ‘petri dish of eccentric local talent unburdened by the pressure to succeed in a larger marketplace’ was likely made possible by a classic suburban paradox: ‘close enough to Los Angeles that we went there all the time, [the Inland Empire] was far enough removed both geographically and culturally that as far as LA was concerned, we might as well not exist.’

And ZOOP! also put Hughes in mind of the pleasures of those early days when both musicians lived in California: ‘the most awesome thing’ that happened to him all weekend, he told Vanderslice, was maybe ‘just arriving at the farm and pulling my car into the lot and parking it next to John’s car … [T]hat moment just felt so normal and domestic and so utterly unlike all of the time we’ve spent together since then, as if we were just showing up for some kind of family picnic in the park or something.’ I wondered if the bassist experienced a similar feeling during the fifth Jordan Lake session, a rehearsal for the Bleed Out tour filmed live and recently distributed by the music streaming service Mandolin. The session had a relaxed, holiday-special feel - much of it felt like the band hanging out, shooting the shit and forgetting the cameras were there. As I sat in my Portland apartment, during the weird time-difference hours when I was still awake and most people I knew had gone to bed, I was glad to see that kind of camaraderie: four dads in their fifties spending a pleasant couple of hours together doing something they loved, ‘having stupid fun’ playing rock music and occasionally remembering we were watching.

Hughes lives in Rochester, New York now, so the Mountain Goats seems to be the main way he and Darnielle get to see each other, and when John called him into the separate vocal booth during the mid-session solo set to sing back-up on a couple of early songs, his face lit up like it was downtown Redding: the expression, I thought, of someone experiencing a genuinely special moment. Just before this, John had taken advantage of the live-taping platform to finally record a performance of ‘Tulsa Imperative’ - an unreleased composition Peter had been so taken by that his band recorded their own version of it in 1994. His bandmate’s next choices were equally surprising: first ‘The Water Song’ and then ‘The Window Song,’ ‘the first song ever recorded with the Bright Mountain Choir,’ the all-female group who provided harmony on some of the Mountain Goats’ early tapes. The bassist hadn’t sung on the original recordings of these tracks, but John must have been sure he would know them, because he’d been around for some of their earliest performances. ‘I know you, you’re the one I spent three seasons trying to pretend that I never knew,’ the two men sang, and no one was trying to pretend anything. They’d known each other, and known these songs together, for thirty years.

Over that time, of course, a lot has changed in the dynamic and profile of the band: there are still intimate solo performances, but it’s hard to imagine an informal event on the scale of ZOOP! taking place today. One of the new songs played at Jordan Lake 5 reflected, as have many of Darnielle’s lyrics since at least ‘The Legend of Chavo Guerrero,’ on the changes in perspective wrought by growing older: ‘Over time people tell me their dreams grow distant / And they learn to love the lives they lead / No more hungry ghosts in the chimney to feed.’ These lines fall in the bridge - where Darnielle says he often aims ‘to put my best stuff’ since getting interested in the Broadway-style ‘emotional payoff’ this element of song structure could provide - of a song called ‘Make You Suffer.’ As such the window into a different, more contented world they seem to offer is inevitably short-lived, which this narrator actually seems to relish. ‘You often hear stories like these,’ he continues, before clarifying his own role in placing such a story of survival and healing out of reach: ‘One day I will see you on your knees.’

But this moment is still where the air gets into the song, where an alternative possibility briefly flourishes: one where loving life is possible by stepping outside of the driving, and sometimes crushing, framework of pursuing your youthful dreams. After all, ‘it’s good to be young, but let’s not kid ourselves.’ At the time, though, nothing feels more powerful, or more important, than your dreams. Which is probably why I connected so strongly with ‘From TG&Y,’ a new song posted to the forums in 2007, and its escalatingly desperate refrain: ‘Hang on to your dreams 'til someone makes you let them go … Hang on to your dreams 'til someone beats them out of you … Hang on to your dreams until there’s nothing left of them.’

Few experiences in my life have been as rewarding as meeting Professor Barry Sanders, John Darnielle’s undergraduate mentor. We sat down for two interviews in Portland, and I can tell already that Barry’s words - about medieval models of craft, laughter, wonder, Lenny Bruce, and the origins of imagination - will resonate throughout the final manuscript. For now, I’ll just tell you one thing he said to me. Sanders was struck by his former student’s refusal to have even solo live performances of his music - like his upcoming benefit shows for the Oregon Institute of Creative Research - advertised under his own name. Here’s how he paraphrased the thinking behind it: ‘Even if I’m performing by myself, I’m always with the Mountain Goats. I’m always grazing with somebody, you know?’ In Claremont, he told me, Pitzer College sits at the foot of the snow-capped Mount Baldy, ‘and in those mountains are goats - are mountain goats. And they’re communal. They’re a family, you know? And that’s how I think John feels about his music - it’s not me doing this, I’m in a crew of people.’

By 2015, Tom Breihan wrote in an earlier Stereogum piece, ‘young men in dark rooms [had] been approaching Darnielle for a couple of decades,’ and in December 2007, I became one of them as John packed his guitar into his case after a short duo set at London’s Union Chapel in support of Micah P. Hinson (though it seemed to me at the time that more people were there for the Mountain Goats). Teenagers like this doubtless remain a demographic within the Mountain Goats crew, but the band has steadily gained purchase with a much wider constituency: one which includes Midwestern librarians, death metal guitarists, green-haired Tiktokers, wholesome cycling dads, really funny video comedians, the original Wonder Woman, Jack Antonoff, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Ken Jennings and the person reading this, whoever you are.

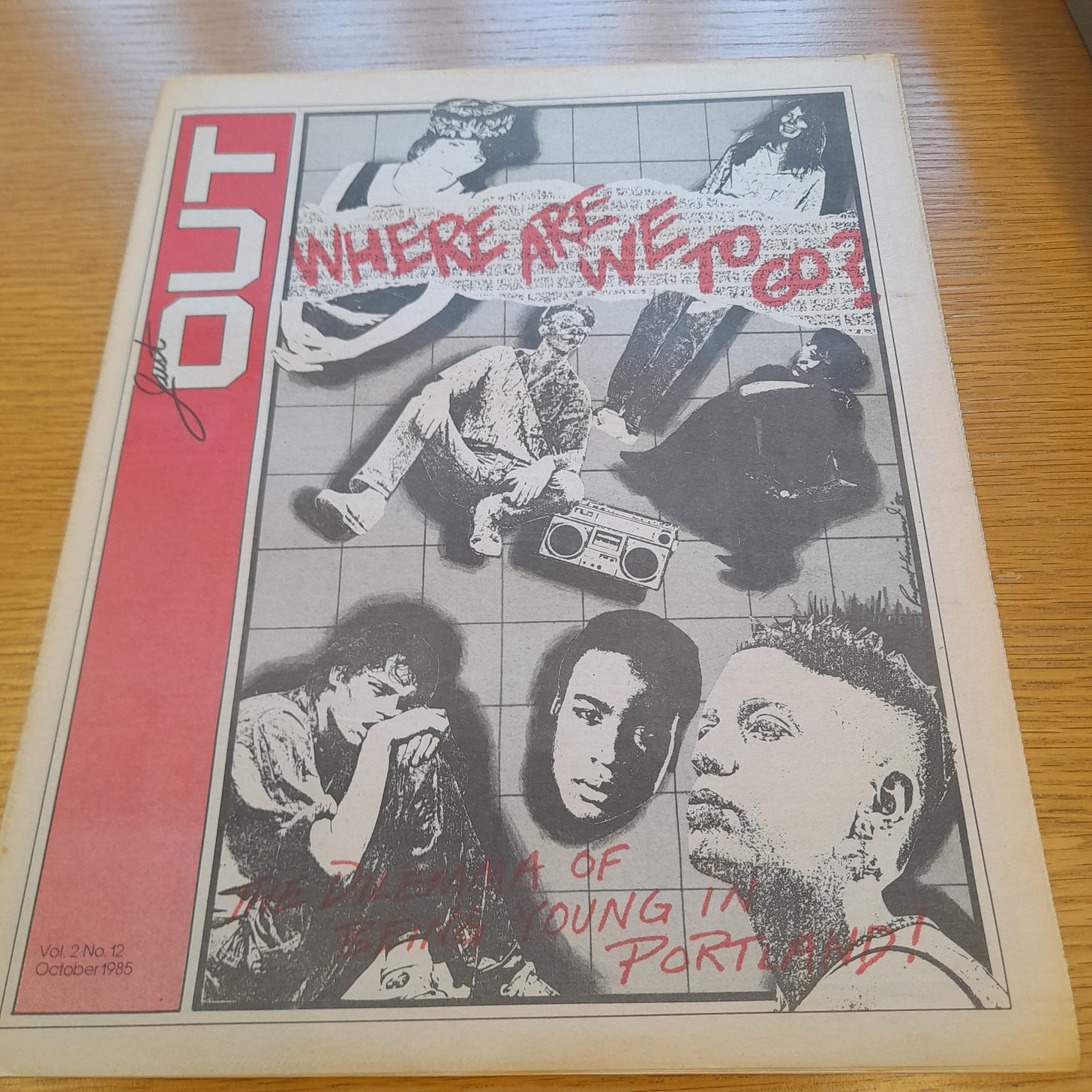

On some nights, I wonder if the audience at a Mountain Goats gig might also look in a certain light like another crowd whose community had a similarly powerful effect on John Darnielle himself: the ‘young men and women in Levi’s and tank tops, people in all styles and manners of black outfits, new wave afficionados in futuristic hairstyles and ‘60s clothing, [and] dancers in various let-my-body-feel-free outfits’ who used to gather at the City Nightclub, the all-ages basement venue at 13th & Morrison which in the Portland of the mid-1980s offered its patrons the only place they could truly be themselves and feel free in the midst of a hostile world.

The sense of defiant self-possession in the face of broader social opprobrium that Darnielle so vividly experienced, there among ‘my people,’ would recur again and again in the music he’d go on to create. In 2008, he’d give a name to this feeling, or something like it: heretic pride. That’ll be the focus of an upcoming chapter. For now, though, I thought you might like to see a couple of appearances the City made, contemporary to Darnielle’s time in Portland, in the archives of Just Out magazine: a local LGBT+ newspaper I spent a rewarding day consulting in the air-conditioned 4th floor Research Library of the Oregon Historical Society. Where else to go, when you’re ready for The Wild Style?

This week, Richard is getting into the Afghani fries at Walter’s.

Transcribed and translated by Andrew Fazzari.

My gosh, the Farm Sanctuary show. I had tickets and a car and a tent but got a call that friends were going to make a last-minute drive into the city to see some bands. I SKIPPED THE FARM SANCTUARY SHOW and I remember regretting it like an hour into my friends arriving. Oof.